As the deadly second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic continues to ravage India, most Indian states continue to be under lockdown. As of May 24, 2021, the total number of Covid-19 cases in India is 2.68 crores, making it the second-worst affected country in the world, after the United States. India is the largest producer of vaccines in the world, producing around 60% of all vaccines worldwide. Yet at the same time, the inoculation drive for Covid-19, cited by the Indian government as the “largest vaccination drive in the world” which started on January 16, has only been able to fully vaccinate 3% of its entire population. At the current average administration speed of 10.8 million per week, it will take until December 2024 to administer all 2 billion doses of the vaccine.

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Following the announcement of the government on May 1st, that vaccinations would be open to all above the age of 18, around 600 million Indians have become eligible for the Coronavirus vaccine. However, at the same time, several states, including Maharashtra, Delhi, Karnataka, Gujarat, have either temporarily suspended the vaccination program, citing shortage in vaccines, or postponed vaccination drives for those between the ages of 18-44. There has been an overflow of blame and misinformation about the vaccine program and policy. While some blame the shortage on India’s decision to export vaccines, others are stating that the government is increasing dosage gaps simply to buy more time to fix this crisis. In this column, we visit the arguments and misconceptions about the Covid-19 vaccine policy in India to attempt to decipher the various causes of the vaccine shortage in India.

IN BETWEEN THE GAPS: UNDERSTANDING THE INCREASE IN GAPS BETWEEN THE TWO DOSES OF THE CORONAVIRUS VACCINE

The announcement of the increase in dosing interval between the Covishield vaccine earlier this month, at a time when vaccine shortages were reported from multiple states, has raised several questions. While many argue that the increase in gaps between the two doses has been conveniently timed to allow the Indian government to buy more time to fix its vaccine shortage, the government maintains that this decision was based only on scientific evidence.

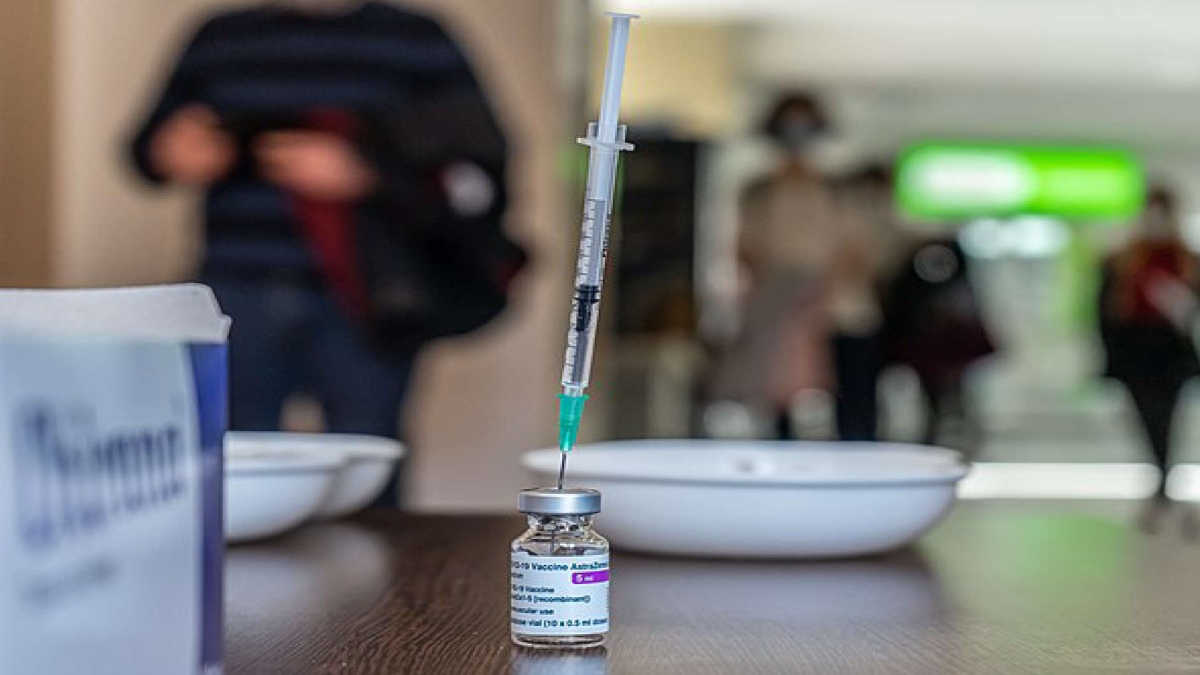

In January 2021, when the Covishield vaccine was approved for emergency use by the CDSCO, the prescribed gap between two doses of the vaccine was 4-6 weeks. Covishield is Serum Institute of India’s version of AZD1222, the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford. The emergency authorization of the vaccine was for healthcare workers, followed by frontline workers.

Shortly afterwards, in February 2021, an analysis published in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed general medical journal, revealed that increasing the inter dose gap to eight weeks would yield better clinical results. The study revealed that AZD1222’s efficacy was around 54.9% when the second dose was given less than six weeks after the first dose. The efficacy increased to 59.9% when the second dose was given 6-8 weeks after the first dose, 63.7% when the second dose was at 9-11 weeks, and 82.4% when the dosing interval stretched to 12 weeks or more. The study analysed data from four clinical trials involving 17,177 participants across Brazil, South Africa and the UK. On March 22, following a meeting of the National Expert Group on Vaccine Administration for COVID-19 (NEGVAC), the government issued a recommendation to increase the inter dose gap to six to eight weeks, but no later than 8 weeks.

However, on May 13, the Union Health Ministry announced that the gap between two doses of Covishield was being further increased to 12-16 weeks instead of the earlier 6-8 weeks. This announcement came at a time when several states in India, including Maharashtra, Delhi, Gujarat, Karnataka had suspended their vaccination drives citing a shortage of vaccines. The government said this increase was based on “available real-life evidence” and “scientific reasons”.

It should be noted India is not the only country that has increased the dosing interval, as in April, Spain also decided to increase the inter dose gap to 16 weeks for vaccine recipients younger than 60 years. As per media reports, NTAGI’s recommendation to increase the inter dose gap was based on the BMJ article, and two additional studies conducted in Bristol and Scotland. While there seems to be some scientific evidence to support the decision to change the gap between the doses of the vaccine, questions about the timing of this announcement, given the reports of shortage of vaccine availability from across the country, are not unfounded.

IS THERE A VACCINE SHORTAGE BECAUSE WE EXPORTED ALL VACCINES TO OTHER COUNTRIES?

Another popular argument floating around about the vaccination shortage in India is rooted in the fact that India exported a significant number of vaccines as part of a global diplomacy program when only less than 5% of its own population is fully vaccinated. Is this true? Let us find out. Under its Vaccine Maitri programme, India has exported and donated more than 66 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines to 95 countries worldwide. It is critical here to distinguish between donations of vaccines, and the commercial obligations of vaccine manufacturers to export vaccines. Out of 66 million, 10.7 million exports were grants from the government, 20 million were as a part of the global COVAX facility, and 36 million were commercial exports.

Out of the 10.7 million doses that have been donated as aid, 7.85 million doses have been donated to neighbouring countries, while 200,000 doses have been given to UN Peacekeeping forces.

India was certainly not the only country exporting vaccines. China exported 240 million vaccines to 60 countries, however, only after it had managed its own COVID 19 crisis. Additionally, the EU has also exported 200 million vaccine doses to 43 countries, but the EU is made up of 27 countries. In comparison, it certainly can be argued that India has exported a significant amount of vaccines when compared to other countries. In fact, one of the worst affected countries by the COVID 19 pandemic, the United States, through the use of its Defense Production Act, made domestic production and use of COVID-19 vaccines its priority, refusing all exports. At the end of March 2021, citing a shortage of vaccines available, India suspended exports. The government further acknowledged that vaccine shortages in India will persist at least until July 2021. The Serum Institute of India (SII) , which is the largest single supplier to the COVAX scheme, has also not made any of its planned shipments since the suspension of exports in March. The SII is a part of the international COVAX scheme run by Gavi, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and WHO to ensure equal access to COVID-19 vaccines.

While donating vaccines to neighbouring countries certainly contributed to the shortage of vaccines in India, the main question that arises is: has the Indian government ordered enough vaccines in the first place? Several policy experts have cited that India’s delay in placing large scale orders for vaccines is the main reason for the shortage of the vaccine across the country. The first purchase of the vaccine (only 16 million doses) was placed in January, while the first large-scale purchase came in March, of 100 million doses from Serum Institute and 20 million from Bharat Biotech. It placed an additional order of 160 million doses from the two companies to be delivered by July. Other countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom placed their first preliminary orders of the vaccine as early as May 2020.

POLICY OF BUYING AND DISTRIBUTING VACCINES IN INDIA HAS BEEN UNCLEAR FROM THE BEGINNING

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Wikimedia Commons

Even now, India has ordered only around 350 million doses of the vaccine, which is sufficient to fully vaccinate 175 million people which is around 12% of the entire population of the country. In comparison, as per data supplied by the Duke Global Health Innovation Centre, the United States has ordered 1.2 billion doses of the vaccine (enough to vaccinate 2 times over), Canada has ordered 338 million (5 times over) and the United Kingdom has ordered 457 million doses (3.6 times over). A senior fellow writing at the Center for Policy Research criticized the ordering policy of the Indian government and said instead of placing large bulk orders, the government is “buying vaccines like monthly groceries”.

The policy of buying and distributing vaccines in India has been very unclear from the beginning, and the government did not address the issue of increasing vaccine supply and buying more stocks before opening up larger populations who would now get vaccinated.

India is the only country in the world where the Central government is not the sole buyer of vaccines and one of the few where vaccinations are not free for all. In April 2021, the central government announced that the states would be responsible for procuring vaccines for the 18-44 age group and that the prices for procurement would be pre-declared by the vaccine manufacturers themselves. Following reports of shortages, governments of Delhi and Punjab alleged that they reached out to international vaccine suppliers Pfizer and Moderna, who refused to send vaccines directly to the state, and stated they shall only deal with the central government.

The confusion does not seem to end there. Many states are also still struggling to dispense the available vaccine stocks. As per a Press Information Bureau release dated May 11, more than nine million Covid-19 vaccine doses available with states and Union Territories are yet to be used. Additionally, since the start of the vaccination drive in January 2021, 4.6 million doses of the vaccine have been wasted as per data shared by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) in response to a Right to Information (RTI) query. As of March 2021, the state with the highest wastage was Telangana (17.6% wastage) followed by Andhra Pradesh (11.6%) and Uttar Pradesh (9.4%). Vaccine wastage can occur at three levels: during transportation of the vaccine, during cold chain point and at a vaccination site — both at service and delivery levels. On the other hand, eight states, including Kerala, West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh, Mizoram, Goa, Daman and Diu, Andaman and Nicobar Islands as well as Lakshadweep have reported ‘zero wastage’, highlighting the importance of reducing vaccine wastage at a time when there is a shortage in supply of vaccines throughout the country. Additionally, as per medical experts, there are over 12 companies and institutions in India that have the capacity and resources to scale up the production of Covishield or Covaxin, to help with the supply crunch. These facilities could have been ramped up to produce more vaccines.

Contributing reports by Damini Mehta, Junior Research Associate at Polstrat and Bhumika Parmar, Raunaq Sharma, Sehal Jain, Interns at Polstrat.