Michelangelo Buonarroti’s renowned Sistine Chapel artwork depicting scenes from Genesis has long captivated art enthusiasts and historians. Recently, it has sparked a unique medical study, as researchers have identified a depiction of advanced breast cancer in one of the figures. This discovery, revealed through a detailed analysis of the painting, suggests that the artist intentionally portrayed the disease, raising questions about his awareness of its existence in the 16th century.

The Depiction of Breast Cancer in the Painting

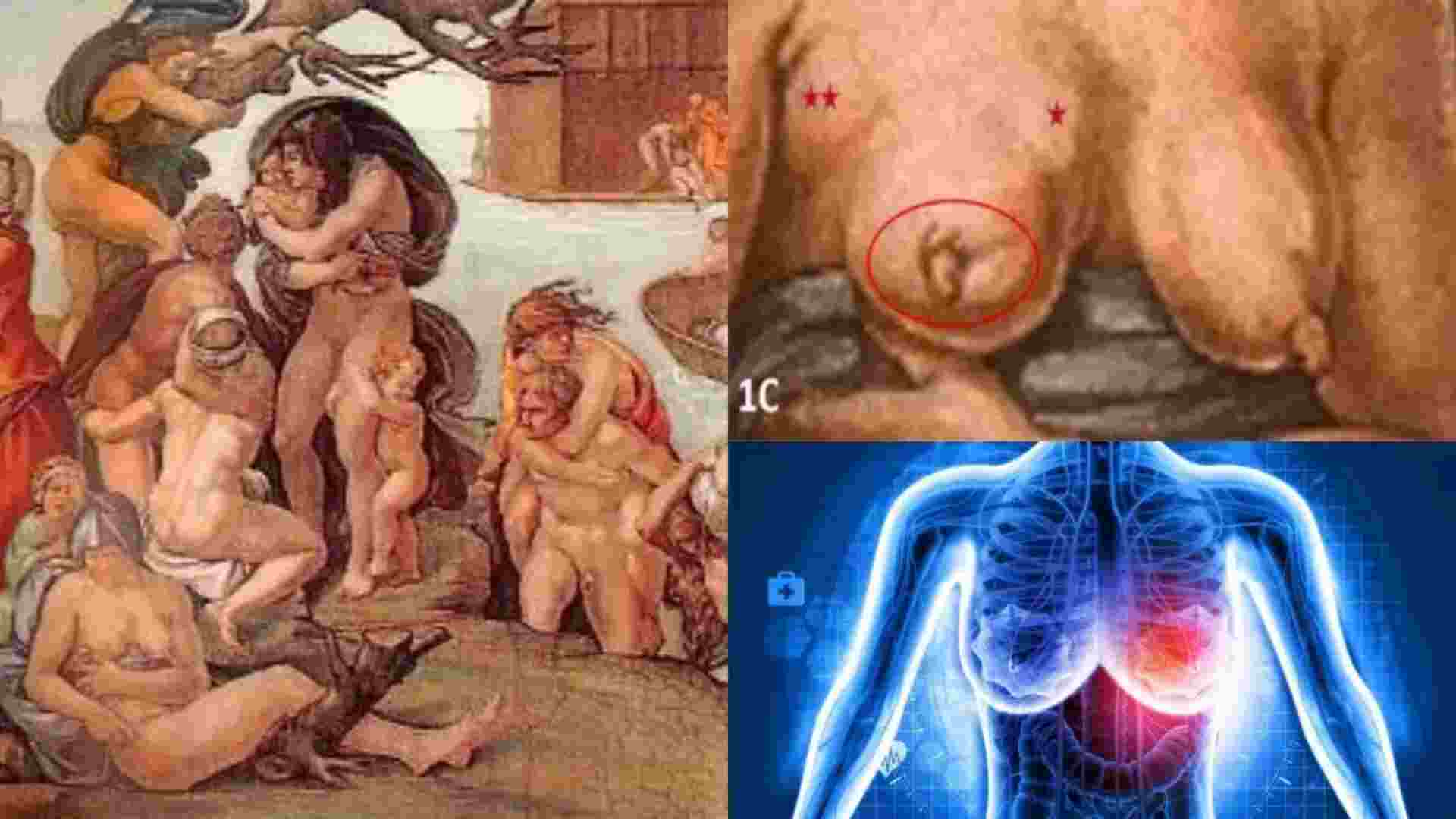

In the section of the painting showing the biblical flood, a semi-naked woman is included among the crowd of figures, seemingly on the verge of death. Art historians and medical experts believe her left breast, which appears aged and shaped by motherhood, shows signs of breast cancer. The shading around the areola, the retracted skin, and the subtle swellings near the armpit are consistent with the characteristics of breast cancer. This figure, wearing a blue headscarf and gesturing towards the earth, suggests she is about to return to dust.

How Was This Depiction Made?

Michelangelo’s involvement with the Sistine Chapel ceiling began in 1508 under the commission of Pope Julius II. The project, which took four years, involved the creation of numerous biblical scenes, including the famous depictions of Genesis. Although Michelangelo initially hesitated to take on the work, he ultimately excelled in his portrayal of the human form. During this period, he likely witnessed a breast deformity in one of the figures and incorporated it into his artwork, intentionally reflecting the physical details.

A team of international experts from diverse fields, including art history, medicine, and genetics, have studied the depiction of this woman in the painting. Their research suggests that Michelangelo’s portrayal of breast cancer was intentional, as they found the characteristics of the breast in the painting to be consistent with medical knowledge of the disease. They also compared these features with those of other figures in the artwork, ensuring the authenticity of their analysis.

Experts believe that Michelangelo’s depiction of breast cancer may not have been a direct copy of a real-life model but rather a result of his deep understanding of anatomy, gained from years of participating in dissections. The precise representation of the disease suggests that he had an awareness of it, which could have been informed by the genetic inheritance of high-risk genes in Europe at the time. Notably, the shading and details of the breast have remained unchanged over the years, further supporting the intentionality of Michelangelo’s depiction.

A Pattern of Depictions

This is not the only instance in which Michelangelo appears to have depicted breast cancer. In a later work, the carving of a feminine figure for the tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici features similar signs of breast deformity. This piece, noticed by oncologists in 2000, adds weight to the theory that Michelangelo intentionally portrayed breast cancer in his artwork.

The recent medical study of Michelangelo’s ‘Genesis’ adds a new layer of understanding to the artist’s genius, revealing a potential awareness of breast cancer centuries before it was formally recognized. Through a combination of medical and artistic analysis, experts have unveiled the artist’s thoughtful representation of the disease, further cementing his legacy as both a visionary artist and a keen observer of the human body.