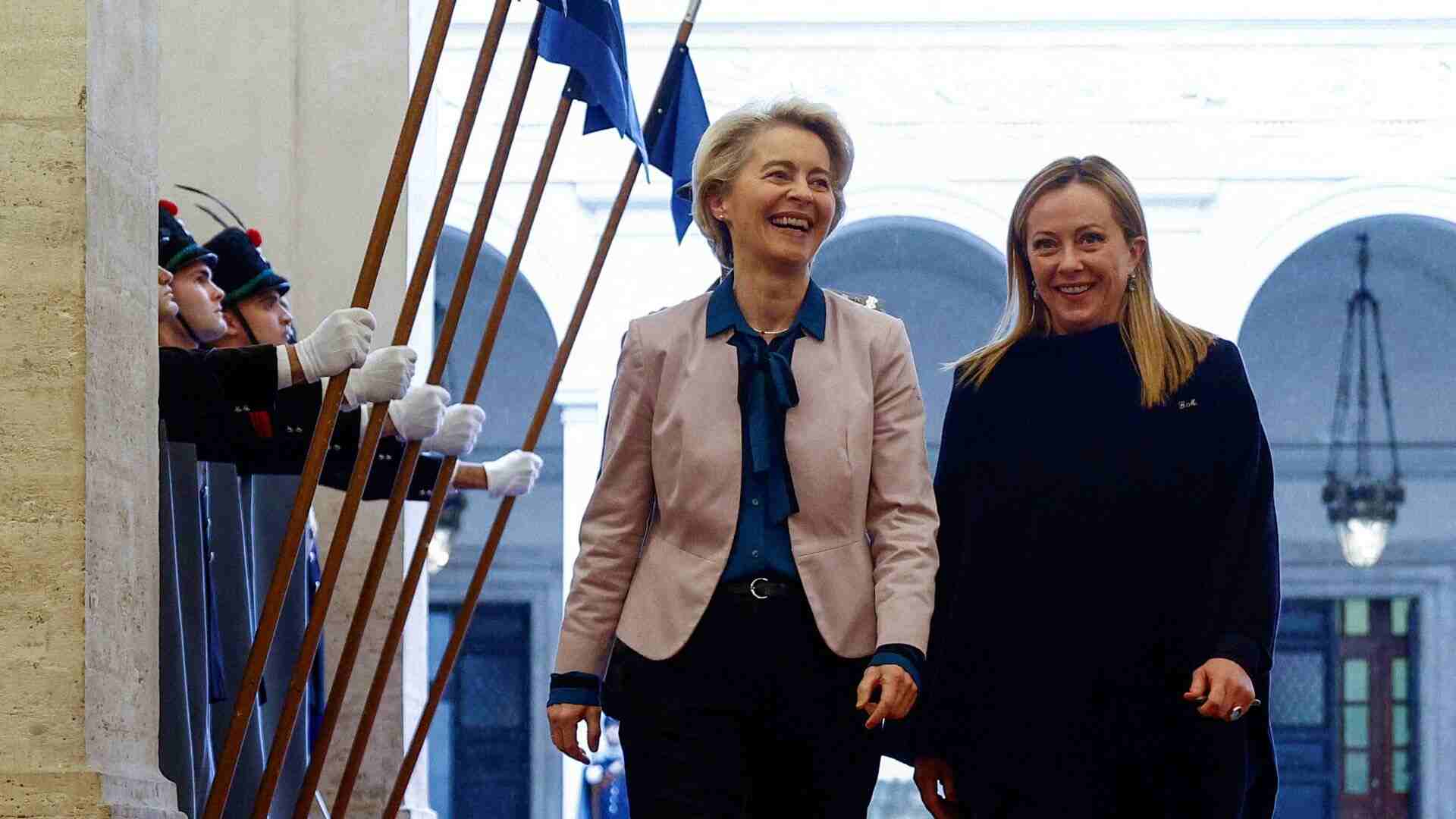

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s decision not to support Ursula von der Leyen for a second term as European Commission chief, according to analysts, was largely influenced by her concern over losing rightwing grassroots supporters. However, this move may potentially limit her influence over key EU decisions.

On Thursday, the European Parliament elected von der Leyen to lead the bloc’s executive for another five years, with backing from center-right, center-left, liberal, and green groups. She secured 401 votes against 284 in the 720-member chamber.

The Brothers of Italy, Meloni’s party and a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists group (ECR), announced its stance post-vote, citing that von der Leyen had leaned too far left, especially concerning green pledges.

While von der Leyen did not require Meloni’s 24 lawmakers to win, the vote represents a departure from Meloni’s previous efforts to maintain amicable relations with the Commission amidst Italy’s significant public debt.

“Meloni cares a lot about being consistent. She had said she would never vote with the left. When it became clear that her votes were not needed, she stuck to that pledge,” stated Giovanni Orsina, a politics professor at Rome’s Luiss University.

This decision, however, disappointed many Italian commentators, who speculated that the Commission might now be less lenient towards Italy’s public finances and its efforts to utilize billions of euros in EU post-COVID recovery funds.

Meloni’s primary concern seemed to be protecting her position at home against her hard-right coalition ally, Matteo Salvini’s League.

“She is afraid of exposing herself on the right, and this fear overwhelmed everything else,” remarked Francesco Galietti from the Rome-based political risk consultancy Policy Sonar.

Core Voters

Brothers of Italy currently polls at nearly 30%—its highest ever—while the League stands around 8.5%. Despite this, Galietti emphasized the volatility of Italian politics and Meloni’s need to retain traditional voters.

Previously considered further right than Salvini, Meloni advocated for Italy to leave the euro zone before moderating her positions after coming to power in 2022.

The European Commission declined to comment on this matter. Von der Leyen, when asked if she regretted seeking Meloni’s support, responded that the vote demonstrated she had adopted the right strategy in gathering supporters who are “pro-European, pro-Ukraine, and pro-rule of law.”

Carlo Calenda, leader of the centrist party Action, criticized Meloni in a radio interview, saying she chose to be “a faction leader rather than a prime minister,” and warned it was “dangerous” for Italy to oppose the EU.

Despite her triumph in Italy’s European Parliament elections last month, contrasted with setbacks for French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, Meloni has faced challenges since then.

Excluded from a deal on the bloc’s top positions, she accused von der Leyen and other leaders of disregarding voters’ wishes by ignoring the surge in right-wing support. She also refrained from supporting von der Leyen alongside groups like the Patriots for Europe, a far-right alliance including Marine Le Pen’s French National Rally (RN) and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s Fidesz.

Less Weight in Europe?

Some analysts suggest Meloni’s stance might be influenced by the prospect of a Donald Trump victory in the upcoming U.S. elections, which could embolden European nationalists. However, Wolfango Piccoli of the political risk consultancy Teneo warned that such a strategy might backfire if Trump adopts an isolationist foreign policy, necessitating stronger European bonds for Italy.

“A plan like that would not be useful to the Italian national interest,” Piccoli noted.

In an interview with Italian daily Corriere della Sera, Meloni asserted she could still collaborate with von der Leyen, dismissing the notion that Brussels would penalize Italy when determining Commission roles. Italy’s candidate is European Affairs Minister Raffaele Fitto.

However, Piccoli indicated that Meloni’s relationship with Brussels might become more complicated, making it harder to influence areas such as defense and migration, although budget procedures are less likely to be affected due to pre-established steps.

“The real question is to count in Europe,” Piccoli concluded.