The humanizing of animals, objects and other things has been a literary device adopted by writers from ancient times. As far as animals are concerned, humanizing them is especially popular in children’s literature be it talking dogs, cats or even a wolf as was the case in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

One of the most inspiring tales in this regard was written more than a hundred years ago, in 1883, by Italian writer Carlo Collodi who hailed from Florence, Tuscany. His work was called ‘The Adventures of Pinocchio and it has spawned several films such Disney’s ‘Pinocchio’ released in 2022 and ‘Pinocchio: A True Story’ by Lions Gate. There is even a Korean drama on the book. The story was somehow rendered more poignant because Pinocchio is actually a puppet crafted from wood with magical properties who longs to be a real boy. Had the story been that of a real boy given to telling lies it would have been nowhere as engaging or memorable.

Some stories, like Pinocchio can be adapted to film more easily than others. On the other hand, there are films that humanise objects which would not work as books. For instance, the film ‘Cars’ released in 2006, is an animation sports drama with talking cars. Set in a world that is populated with anthropomorphic cars the film was a box office success, but would not have worked as a novel.

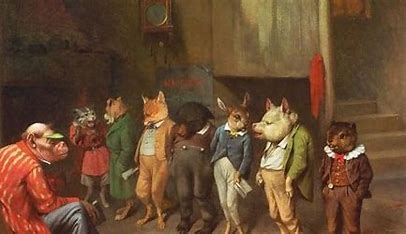

Leaving aside children’s fiction humanizing animals has also been a literary device resorted to in the writing of adult fiction. Most famously the pig was humanized in George Orwell’s classic ‘Animal Farm’, a book that can be enjoyed at multiple levels, as simply a story but also as a satire on totalitarian regimes. The last line of that novella stayed with the reader long after he had closed the pages of the book. ‘The creatures outside looked from pig to man and from man to pig and from pig to man again but already it was impossible to tell which was which.’

It is also possible to humanize something that is not tangible in physical terms, at least not apparently so. In this regard we may look at ‘The Emperor of All Maladies’ by Pulitzer winning Indian-American author Siddhartha Mukherjee, published in November, 2010. While a work of non-fiction, in the writing of it, he has humanized cancer one of the leading causes of death in the world and has garnered praise and a wider readership for his book. Some have even described it as being akin to a detective story. The author has himself described it as similar to a book on military history ‘in which the adversary is formless, timeless and pervasive.’ ‘Here too,’ Mr Mukherjee goes on to write, ‘there are victories and losses, campaigns upon campaigns, heroes and hubris, survival and resilience – and inevitably the wounded, the condemned, the forgotten, the dead.’

Creative writers often search for appropriate subjects to humanize. The great merit in such an approach is that it makes the story that is told resonate with a far greater readership. The cancer story was a great one to tell given that it is one of the major causes of death worldwide and also given Mr Mukherjee’s expertise as an acclaimed oncologist. Incidentally, the author lost his own father to that dreaded disease so that makes the book all the more poignant apart from being immensely educative. What about the corona virus? Many works of fiction were written on and around it, even if no notable work emerged in which the virus itself was humanised.

The humanising of ‘cancer’ or ‘corona’ for that matter, to tell a tale and engages and engrosses the reader is no simple matter. A considerable degree of literary expertise is called for to pull it off with panache. What is this the case? For instance, to take the case of corona, the characteristics of the virus must match those of a potential fictional humanlike entity called upon to represent it. Unlike small pox, measles, or polio there were no outward marks on the sufferer’s body. It could be argued that for this reason the female species could represent corona better than the male. In other words, Madame Corona might be a better literary choice as compared to Mister Corona. We are just getting started here. It is not enough that corona is feminine and not masculine. Other features of the virus may require representation in what kind of a woman this is. The humanising of an animal, object or thing is a craft that requires both intelligence and creative imagination, something that only a few authors may be adept at.

Personification is different from anthropomorphism. If a bed looks at a character ‘invitingly’ that’s personification. On the other hand, if a bed stands up and starts walking towards to you, as it speaks to you, that’s anthropomorphism. If a tree stretches its arms towards a character that’s personification, but if the tree starts chasing the character, that’s anthropomorphism. It will however require considerable talent to create a convincing portrait of the latter scenario. A writer like Stephen King might be able to pull it off, but most writers would find such a task far too challenging.

What else? Cancers and viruses have existed for thousands of years, but now new killers have emerged that need literature to represent them. For instance, according to the World Health Organisation air pollution kills seven million people every year. The organisation estimates that 4.2 million people die from outdoor air pollution and 3.8 die from indoor air pollution. Now, given the direness of the situation, wouldn’t it make sense for a novelist or playwright for that matter, to humanise air pollution?

There is no reason why this cannot be accomplished and it be featured as an important or principal character in a short story, play or novel. Certainly, such a work could resonate with urban audiences across the globe who live in crowded polluted cities where the toxic air is slowly but surely shortening their lives.

Authors, are you listening?

(Rajesh Talwar, the author of forty books spanning multiple genres, has served the United Nations for over two decades across three continents. His most recent book is titled ‘The Killings in November: A Play on Toxic Terror’)