The Covid-19 vaccination drive in India, referred to as the “largest vaccination drive in the world” by the Indian government, kickstarted on 16 January 2021. The entire country rejoiced as Manish Kumar, a 34-year-old sanitation worker received the first jab of Bharat Biotech’s Covaxin at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in New Delhi. Since then, India has administered a total of 25.53 crore doses (including first and second doses) of Covid-19 vaccines. Out of the 25.53 crore doses that have been administered, roughly 11.21 crore doses have been administered to men, while 9.56 crore doses have been administered to women, and roughly 27,970 on others (as of 14 June 2021). Over 2 crore more men than women have been vaccinated during the first five months of the vaccination programme, which projects a growing gender gap. As per an analysis of National Family Health Survey data, historically, full immunization is much lower among female children, and there has been a significant gender disparity in the administration of BCG, DPT, polio, and measles vaccines. Covid-19 vaccination trends seem to follow the pattern.

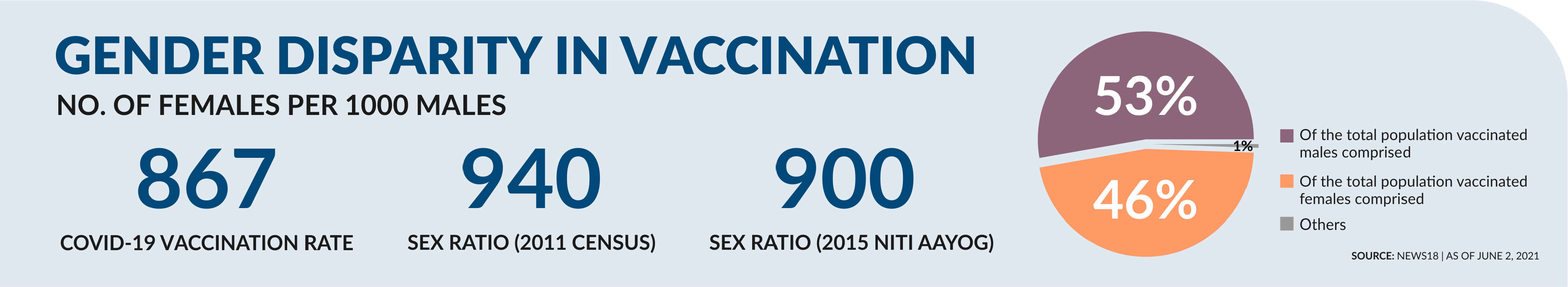

For every 1,000 men receiving the Covid-19 vaccination (first or second dose), roughly only 852 women are getting vaccinated, which is much lower than India’s already skewed sex ratio of 900 (Niti Aayog, 2015). Some of the worst-performing states include Delhi where the gender gap as of 14 June is 722 females vaccinated per 1,000 males while the sex ratio is 821 females per 1,000 males ; Jammu and Kashmir, where the vaccination gender gap is 712 as compared to the sex ratio of 892; Uttar Pradesh where the vaccination gender gap is 741 as compared to the sex ratio of 898. Other poorly-performing states include Punjab, where the vaccination gender gap is 770 as compared to the sex ratio of 876, and Nagaland where the vaccination gender gap is 755 as compared to the sex ratio of 900.

On the other hand, the least gender gap in Covid-19 vaccination has been recorded in Kerala where the vaccination gender gap is 1075 females as compared to the sex ratio of 1058, Andhra Pradesh with 1071 females vaccinated for a sex ratio of 978, Chattisgarh where 1045 females are vaccinated for a sex ratio of 989, and Himachal Pradesh where the vaccination gender gap is 979 as compared to the sex ratio of 968.

While one aspect of the growing gender gap in Covid-19 vaccination is the skewed sex ratio in India, in that, females comprise roughly 48% of the population and males roughly 52%, the gender gap in vaccination is much higher than this disparity. The inequality between males and females in India in the areas of access to healthcare, technology, and literacy rates has a multiplier effect on the vaccination gender gap, which has widened in the last five months, since the start of the vaccination programme in the country. In addition to this, social stigma and other cultural divides between males and females, which are even more prevalent in rural areas, also have an impact on this.

DECODING THE VACCINE GAP

The vaccine gender gap cannot be viewed through an isolated lens. The overall inequitable access to healthcare coupled with systemic problems such as lack of facilities to promote women’s health and lack of education play a role in this widening gender gap. Hesitancy to opt for the Covid-19 vaccine, compounded by the digital divide of access to vaccines, are perhaps two of the most important factors playing a role in increasing the gender gap. As per the National Family Health Survey, conducted in December 2020, on an average, less than three out of 10 women in rural areas and four out of 10 women in urban areas in India have ever used the Internet. Currently, the only way to register for the Covid-19 vaccination programme is through the Government of India’s online portal, COWIN. Due to digital illiteracy, most women in rural and in fact low-income urban households cannot register themselves for the vaccination, creating a huge technology gap. In addition to this, illiteracy has been attributed as one of the main reasons for the misconceptions around the Covid-19 vaccines. On top of this, the female literacy rate in India (70.3%) is significantly lower than the male literacy rate (84.7%), having an even bigger multiplier effect on their access to knowledge about healthcare. Misinformation is another key factor in the low vaccination turnout, and this impacts women more. Several misconceptions, such as getting vaccinated during menstruation leads to blood clots, the effect of vaccines on fertility, and the vaccine being harmful to pregnant and lactating women, are all a result of miscommunication and lack of proper knowledge about healthcare through verified and appropriate channels, which adversely affect women’s willingness to get vaccinated.

Systemic gender inequality in access to healthcare also contributes to the gender gap of vaccination. According to a research study conducted by Harvard University, only 37% of women in India have access to healthcare, as compared to 67% of men. Gender continues to be a barrier across rural and low-income Indian households. Cultural practices, socio-economic status, cost expenditure on health, and perception of illness all have a consequential impact on gender discrimination in access to healthcare services in India.

Additionally, cultural divides and gender norms add to a growing gender divide. In most rural households in India, women have less autonomy to make decisions about their healthcare, their bodies, and their lives, as compared to their male counterparts. Add to this the fact that overall in low income and rural households, there is reduced spending on women’s nutrition and healthcare services, and preference is always given to males in the household for spending money on healthcare services. As per the fourth National Family Health Survey, only 40% of women are allowed to go out alone, including to a health facility. Most females in Indian households are dependent on the men in their families. All these factors affect and limit their access to adequate healthcare.

GENDERED POLICY MAKING: A SOLUTION TO OVERCOME THE GAP

Photograph by Creative Commons

Photograph by Creative Commons Photograph by Creative Commons

Photograph by Creative Commons Photograph by Creative Commons

Photograph by Creative Commons

Women face plenty of roadblocks to receiving healthcare and consequently, their protection against Covid-19 is affected. So what is the solution? The most essential need is to adopt an approach that takes gender disparity into account while making policies surrounding healthcare, especially for programmes such as the Covid-19 vaccination drive, to help women overcome recurring and consistent barriers. The World Health Organization (WHO) has called for countries to address gender-related barriers in the planning and roll-out of vaccine distribution schemes to enable vaccinations to reach everyone, especially those who are marginalised. It also adds that employing women vaccinators is key to closing the gender gap in access to Covid-19 vaccination. In India, where the majority of paramedical staff, ASHA workers, and anganwadi workers are female, incentives, training programmes, and educational drives need to be undertaken to motivate women at the grassroots to opt for the Covid-19 vaccines. Similarly, at the rural level, female panchayat leaders and heads should be educated to motivate and help women from their communities get vaccinated. Having women-only vaccination centres, or having reserved time slots at vaccination sites only for women, and moving away from only digital registration for vaccination slots, will also prompt more women to get vaccinated.

State and central governments, as well as health departments, need to invest in social campaigns to address misconceptions about vaccinations, especially those surrounding the impact of the vaccine on pregnant, lactating, and menstruating women. Because of the profound inequality in almost every sphere, including access to education, healthcare, technology, cultural, and social stigmas, any crisis has a greater impact on females in India. Timely vaccination is the only solution to protect populations from the ravaging impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. If steps are not taken to close the gender gap in vaccination programmes, the long-lasting impacts of the pandemic on Indian gender statistics (including literacy, health, income, and employment,) which are already among the worst in the developing world, could be catastrophic.