As of 01st January, the central government has implemented its new integrated food distribution scheme which will provide free foodgrains to 81.35 crore beneficiaries in 2023. The scheme has been designed to strengthen the provisions of the National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013 in terms of the accessibility, affordability, and availability of food grains for poor households. The NFSA 2013 aims to provide subsidised food grains to approximately two-thirds of India’s population. Around 58 per cent of the Indian population is engaged in agriculture and allied activities, the availability of food and food security continues to be a major problem in the country, given the increasing population, low agricultural productivity, reduction in the availability of farmable land, and the impact of climate change on agricultural production.

According to the United Nations Office in India, there are around 22.45 crore medically undernourished people in India, which accounts for around a quarter of the world’s hunger burden. India also ranks 68 out of the 113 major countries in terms of food security. Food security in India is marred by various challenges, including inadequate food distribution, a lack of awareness about farming and agricultural productivity, and a lack of investment in technology to improve farming techniques and productivity. While the free-of-cost provision of food grains is likely to alleviate the food security pressure on the population in the short term, economists caution that the financial burden of such a policy, in the long run, could cause more harm than good.

What is the new integrated food security scheme?

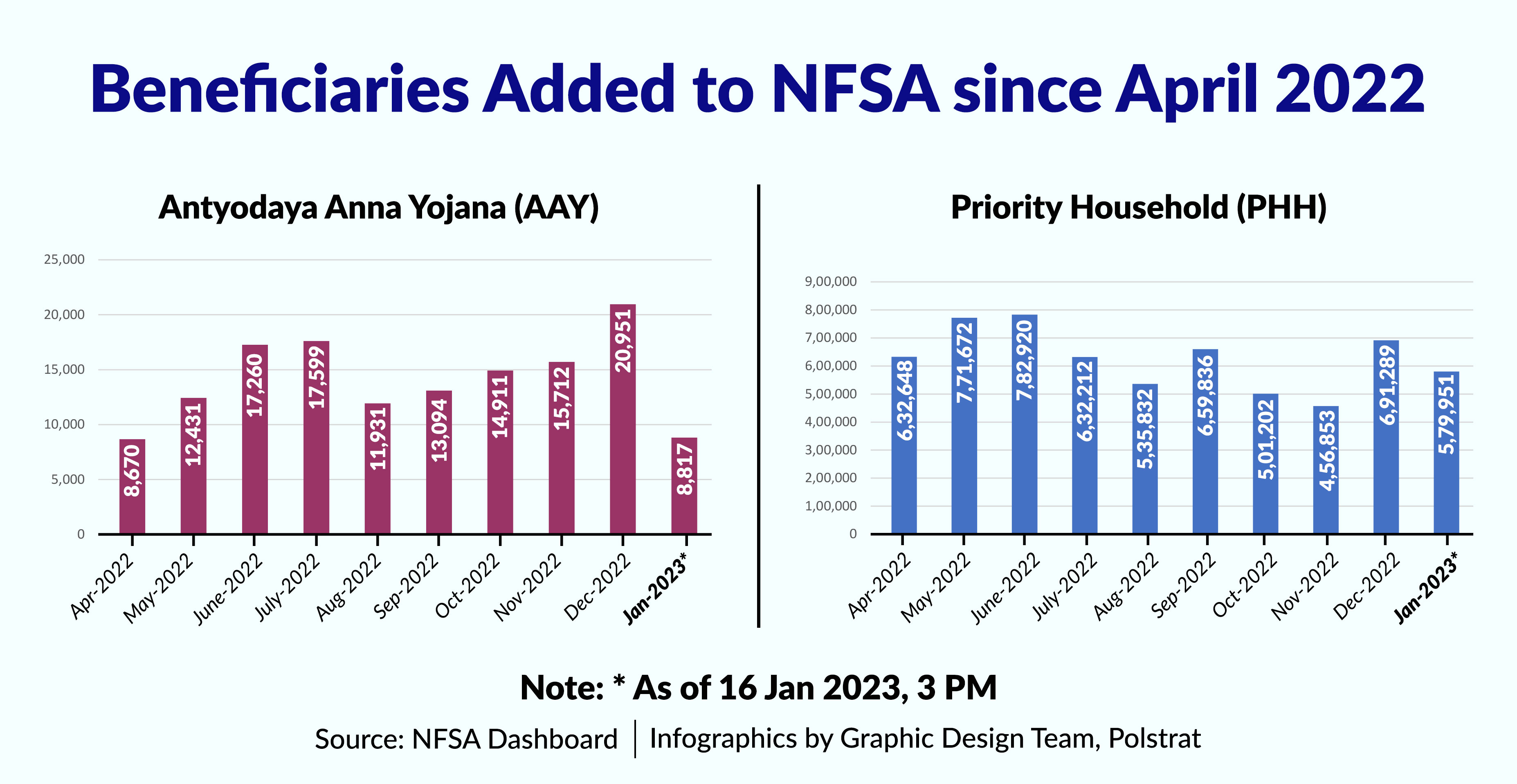

The Indian government rolled out the new integrated food security scheme for providing free foodgrains to Antodaya Ann Yojna (AAY) and Primary Household (PHH) beneficiaries on 01st January 2023. The scheme has been named the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Ann Yojana (PMGKAY). If the new integrated food security scheme is successfully implemented, it will ensure the effective and uniform actualisation of the NFSA. The scheme has been launched to fulfil the central government’s vision of One Nation – One Price – One Ration.

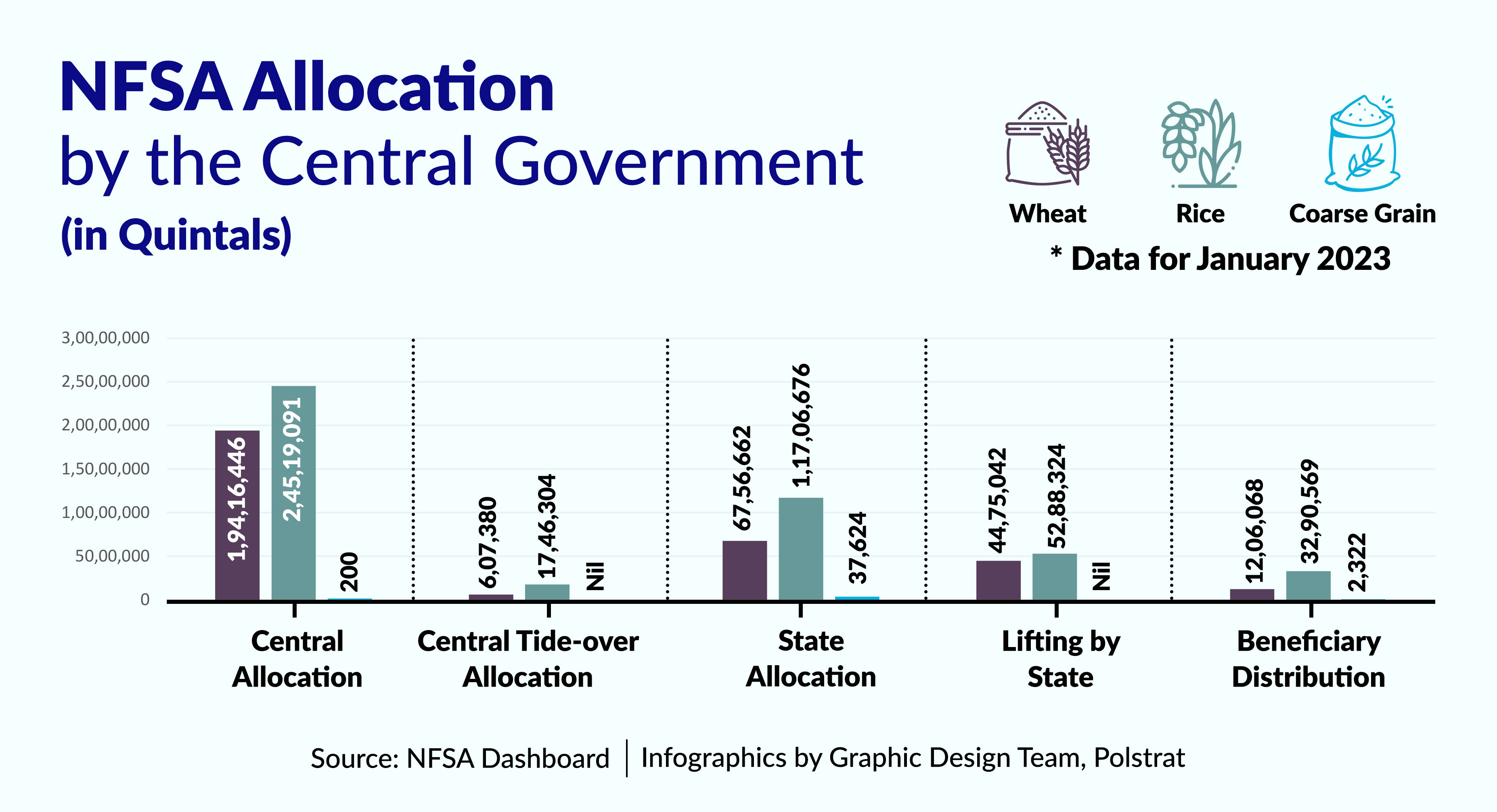

The integrated scheme aims to subsume two current food subsidy schemes which were implemented by the Department of Food and Public Distribution. The first is the Food Subsidy to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) under the NFSA and the second is the Food Subsidy for Decentralised Procurement states which deals with procurement, allocation, and delivery of free foodgrains to the states under the NFSA. The Union Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, Commerce & Industry and Textiles, Piyush Goyal highlighted that under the scheme, five kilograms of food grains per person will be allocated to Priority Households (PHH) beneficiaries while 35 kilograms per household will be allocated to the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) beneficiaries in 2023. It is estimated that the central government will spend around Rs. two lakh crore in the upcoming year on food subsidies under the NFSA 2013 and other welfare schemes to help alleviate the food security burden on poor households. The central government is taking measures to ensure the smooth implementation of the new PMGKAY. Steps, including issuing necessary notifications for making the price of foodgrains zero for AAY and PHH beneficiaries, resolution of technical issues at Fair Price Shops (FPS), advisory related to margin to the FPS Dealers, and zero prices in the print receipts given to beneficiaries, have already been issued. As per government reports, officers of the Department of Food & Public Distribution and FCI are regularly interacting with various State Government officers to ensure the smooth rollout of the scheme. Government records show that as of 16th January 2023, 79.19 crore beneficiaries have benefitted from various schemes and programmes under the NFSA. Overall, the central government has allocated over 4,93,719 Fair Price Shops across 34 states in India to ensure the effective implementation of the scheme.

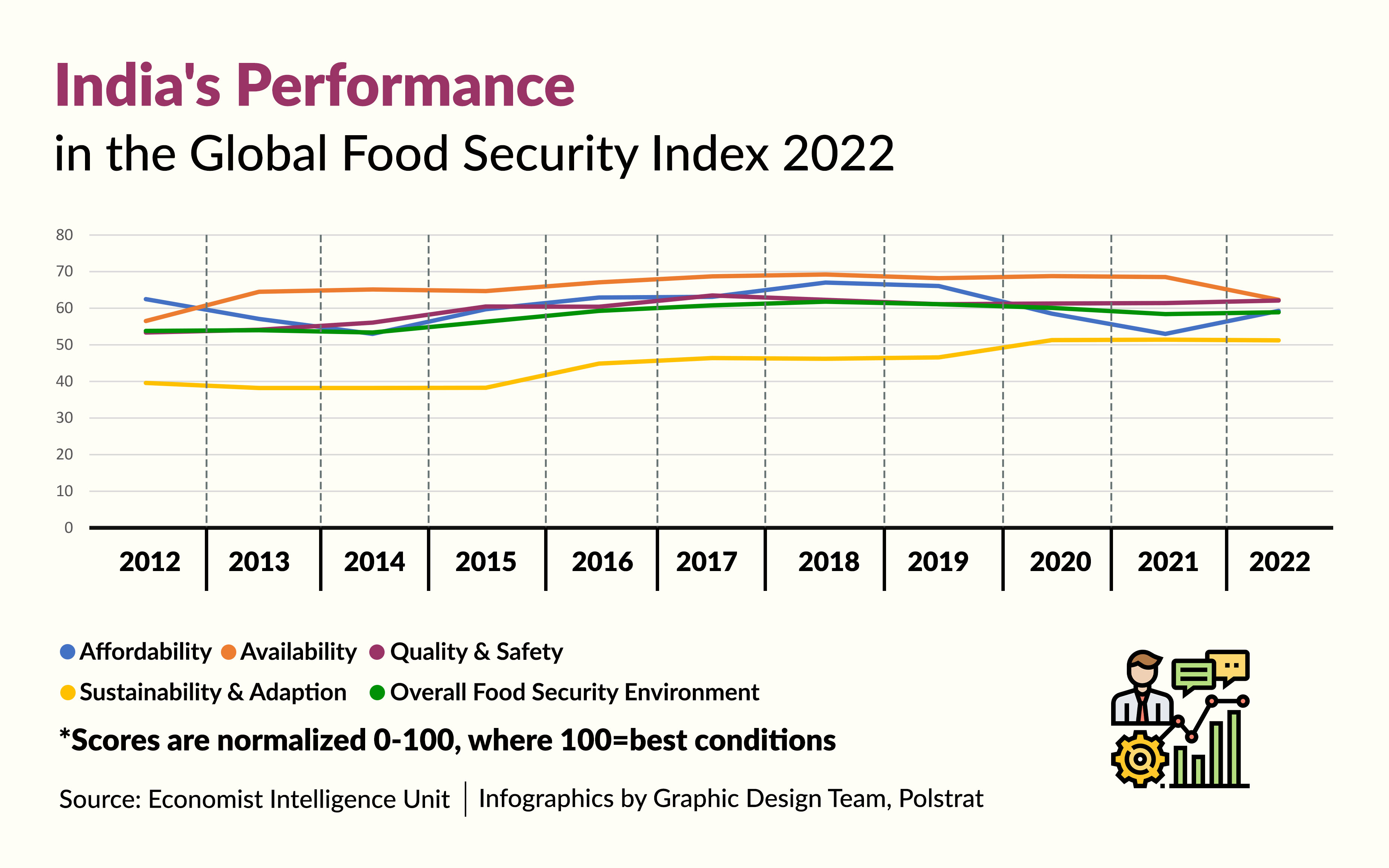

India ranks 68 on the Global Food Security Index

Despite the implementation of the NFSA and various other food security measures and schemes, India still stands at the 68th position on the Global Food Security Index.

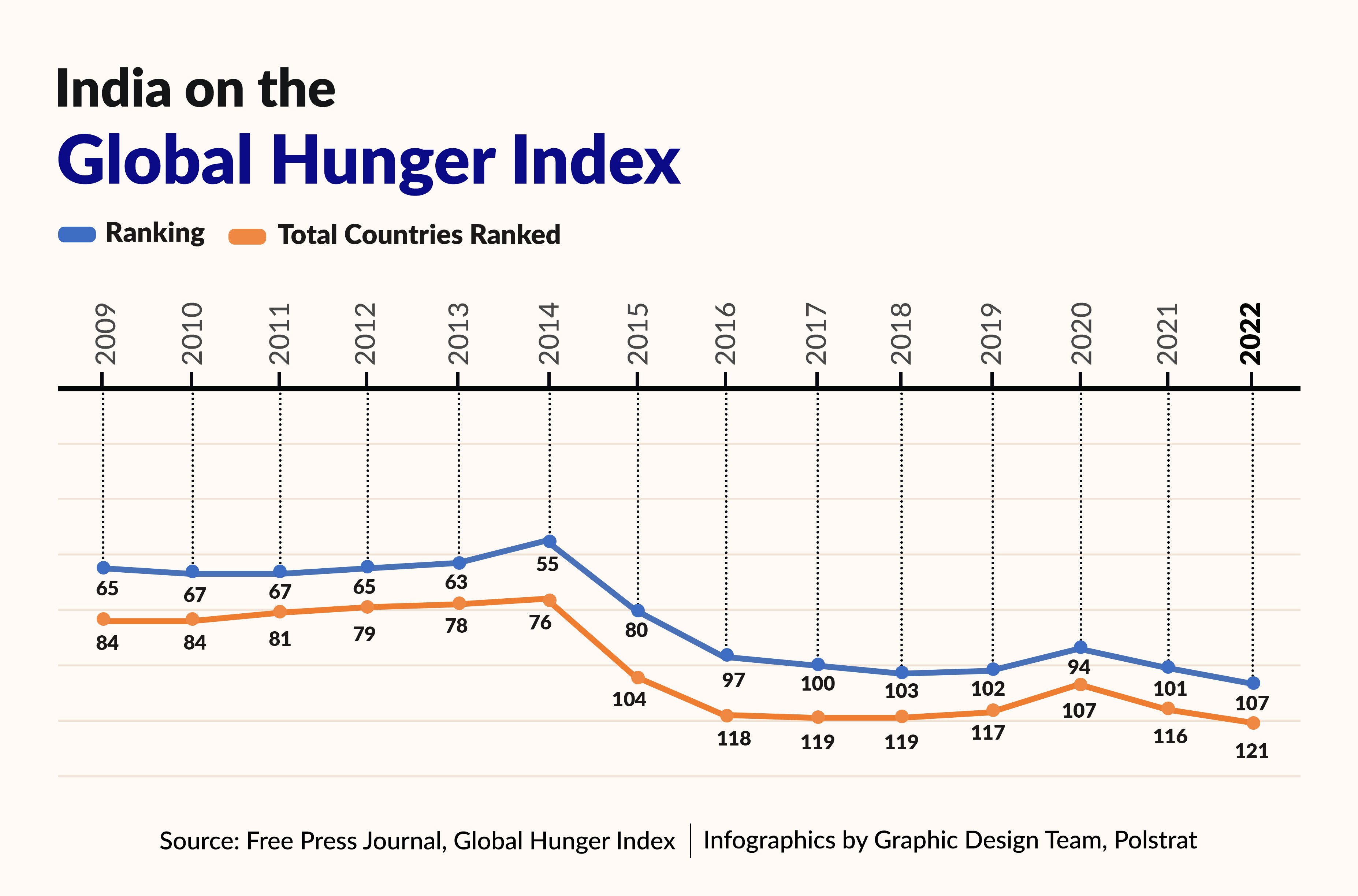

This does mark an improvement from the previous year, where it held the 71st position. Similarly, its rank in the Global Hunger Index is also very low – it held the 107th rank in 2022, a huge downfall from the 63rd position it gained in 2013.

However, the government of India issued a press release in October 2022, stating it believes the Global Hunger Index is “erroneous” and suffers from “serious methodological issues”. “Misinformation seems to be the hallmark of the annually released Global Hunger Index,” the press release said. Some of the key issues of the food distribution system in India, as highlighted by various social scientists and economists, is that those without a ration card, including those who do not have the required documents or are left out of the census, do not receive the benefits of any food subsidy schemes. The government has attempted to combat this through the implementation of nationwide portability of ration cards under the “One Nation, One Ration Card” (ONORC) scheme.

Alongside the implementation of the integrated scheme, 2023 also marks the year of India’s G20 presidency. The number of people affected by hunger is projected to exceed 840 million by 2030 and amid the global food crisis, India is leveraging its presidency of G20 to further promote global food security, nutrition, and food systems. As G20 President, India is also investing in both shortand long-term strategies related to climate-smart agriculture.

The government is focusing on building inclusive value chains and food systems along with bringing digital transformation to the agriculture sector in an attempt to solve the global hunger crisis. India is also attempting to cater to global food demand in times of crisis by exporting 1.21 Lakh Metric Tonnes of foodgrains.

While many are applauding the new integrated food security scheme as it would directly improve the lives of crores of beneficiaries, others are highlighting the fact that it is not desirable to make foodgrains entirely free. Former agriculture secretary, Siraj Hussain, highlighted that the new scheme is estimated to have an additional burden of around Rs. 15,000 crores on the government. He went on to highlight that the NFSA enables the government to revise the central issue price of foodgrains after three years, and a revision of prices was overdue. However, the decision to make foodgrains completely free of cost till December 2023 would mean that the government is unlikely to charge anything for foodgrains even in AprilMay 2024 as the national elections are likely to be held at the same time. Many economists have similarly highlighted that after this instance, any government might find it difficult to charge for foodgrains under the public distribution system, which could make the policy a fiscal burden on the central government in the long run.