United States President Donald Trump’s extensive tariff program, among the most ambitious in modern US trade history, is now being closely scrutinized in American courts. Last week, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in Washington, DC, ruled 7-4 that the administration exceeded its authority by using the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose broad tariffs on multiple trading partners. The judges clarified that IEEPA, originally intended for national security or foreign emergency situations, does not grant the president unlimited power to levy tariffs.

The court reviewed two major sets of tariffs. The first was the “reciprocal” tariffs introduced in April 2025, targeting a wide group of US trading partners. The second included duties announced in February against China, Canada, and Mexico, which the administration justified as necessary to combat fentanyl imports. The ruling, however, did not affect other tariffs imposed under separate laws, such as the 2018 steel and aluminium duties. The court allowed the contested tariffs to remain in effect until October 14, giving the administration time to appeal to the Supreme Court. If upheld, the decision could significantly alter Trump’s current tariff framework.

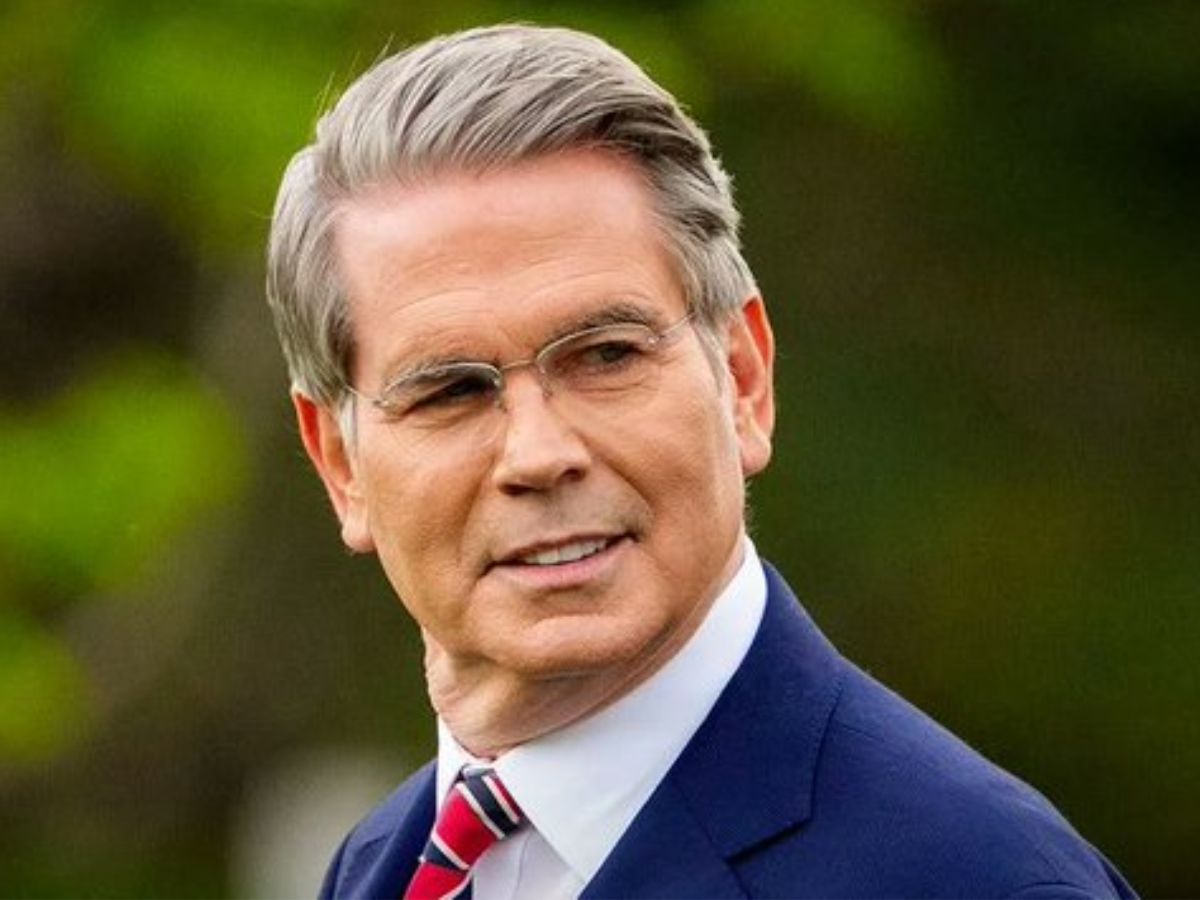

Treasury Secretary Defends IEEPA Tariffs

US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has strongly defended the use of IEEPA, describing it as a crucial response to long-standing economic and security threats. Speaking to Reuters, he said, “I’m confident the Supreme Court will uphold it – will uphold the president’s authority to use IEEPA. And there are lots of other authorities that can be used – not as efficient, not as powerful.”

Bessent is preparing a legal brief for the US solicitor general emphasizing two points: the persistent US trade deficits threaten economic stability, and the fentanyl epidemic constitutes an extraordinary emergency. He noted, “We’ve had these trade deficits for years, but they keep getting bigger and bigger. We are approaching a tipping point … so preventing a calamity is an emergency.” He also drew parallels with the 2008-2009 financial crisis, suggesting that early interventions could have reduced the impact and that current trade and drug threats require similar proactive measures.

Scope and Purpose of Tariffs

Under IEEPA, Trump has imposed tariffs on imports from multiple countries, covering both broad categories of goods and specific products. The administration frames these measures as enforcing “reciprocal” treatment, with US tariffs matching levels charged by trading partners.

Some tariffs are also tied to national security objectives. In February, additional duties targeted China, Canada, and Mexico, directly linking them to efforts to curb fentanyl, a synthetic opioid responsible for tens of thousands of deaths annually. Bessent told Reuters, “If this is not a national emergency, what is? When can you use IEEPA if not for fentanyl?” While critics questioned whether tariffs are an effective tool for drug enforcement, the administration argued that economic leverage can pressure foreign governments to act.

These tariffs continue the approach from Trump’s first term (2018–2020), when duties were imposed on steel, aluminium, solar panels, washing machines, and hundreds of billions of dollars of Chinese imports, reshaping US trade relations. Many of these remain in force under the Biden administration.

Plan B: Alternative Legal Routes

Bessent emphasized that IEEPA is not the only option. Other legal authorities within US trade law could maintain tariffs if the Supreme Court strikes down the current approach. One potential pathway is Section 338 of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, allowing tariffs up to 50% for five months on imports from countries discriminating against US commerce. While rarely used and historically controversial, it provides a backup mechanism.

Other statutes include:

-

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 – allows tariffs on imports threatening national security. Trump has used this for steel, aluminium, and automobiles, with more investigations underway for semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, timber, aircraft, and other products.

-

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974 – allows tariffs if imports seriously injure US manufacturers, capped at 50% above existing rates and lasting up to eight years. Used in 2018 for solar panels and washing machines.

-

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 – permits tariffs in response to discriminatory trade practices without a cap, historically used against China. New investigations, such as into Brazil, have also led to recent tariffs under IEEPA.

-

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 – allows temporary tariffs of 15% for 150 days to address balance-of-payments issues, requiring congressional approval for extensions.

Also Read: Why Border Disputes Still Spark Wars: The Cambodia–Thailand Conflict Explained