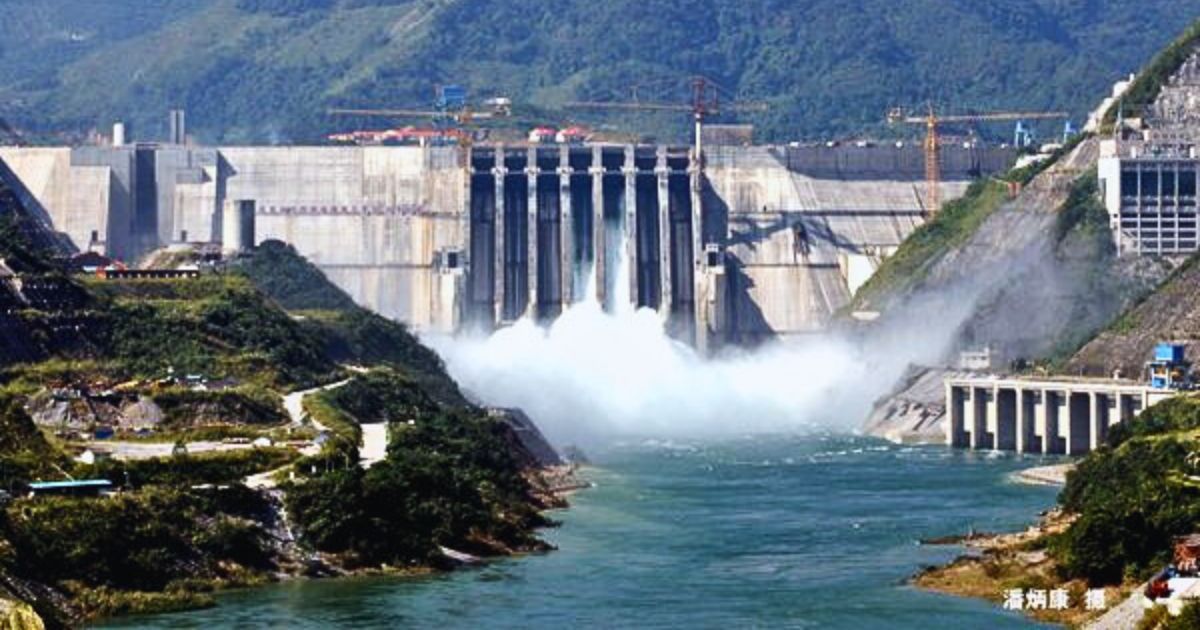

In a move that has triggered deep strategic anxiety in India, China has officially begun construction on a colossal $170 billion hydropower project on the Yarlung Zangbo River, just before it crosses into Arunachal Pradesh as the Brahmaputra. The project, expected to generate 60 GW of electricity, is the largest infrastructure push from China since the Three Gorges Dam and is being hailed as a major stimulus for the country’s economy.

The announcement was made by Chinese Premier Li Qiang on July 19, with state-run Xinhua confirming that a new entity—China Yajiang Group Co Ltd—will build and operate the project. Spread across a 50-kilometer stretch of the river that descends nearly 2,000 meters, the project will consist of five cascade hydropower stations. While typical cascade systems involve flow-regulating storage dams, China has not revealed the extent of water storage planned—a critical detail that could determine its influence over downstream river flow into India.

Chinese stock markets responded enthusiastically, with shares of construction and hydropower firms surging after the announcement.

The ‘Water Bomb’ Concern

Across the border in Arunachal Pradesh, China’s dam-building ambitions have stirred deep concern, especially in the ecologically sensitive and ethnically diverse Siang region. Chief Minister Pema Khandu, in a statement earlier this month, warned that the dam posed a threat second only to the military one from China. Calling it a potential “water bomb,” he said any abrupt release of water could devastate entire communities along the river, particularly tribal groups like the Adi.

Khandu pointed out that even if the majority of the Brahmaputra’s water comes from within India, nearly 30 percent originates in China. The immediate threat would be felt in Arunachal, he said, where unannounced discharges could wash away homes, farmland, and lives.

While the Chinese have maintained strategic silence on the project’s impact across borders, Indian officials are closely monitoring developments amid fears of both ecological damage and strategic coercion.

Downstream Development Disrupted

Beyond flooding risks, the dam could significantly affect India’s own hydroelectric plans in the Northeast. The region holds nearly half of the country’s untapped hydropower potential—about 50 GW of which lies in Arunachal Pradesh alone. Sudden changes in water flow from the Chinese side could jeopardize future Indian hydro projects, throw off seasonal river behavior, and impact biodiversity downstream.

The opacity surrounding China’s intentions and lack of water-sharing agreements only deepens India’s unease.

India’s Strategic Counter: The Stalled Upper Siang Project

India has long planned the 11.2 GW Upper Siang Multipurpose Project, a major storage-based hydropower project in the Siang area of Arunachal Pradesh, to offset the upstream growth. It is envisioned not just as a power generator, but as a regulatory dam capable of controlling water flow in the event of sudden releases or diversions by China.

But despite the strategic urgency, little has been accomplished. Important investigations are still on hold three years after NHPC Ltd. was given the task of creating a pre-feasibility report by the Ministry of Jal Shakti. Local resistance and environmental concerns have slowed down momentum.

Responding to questions about the delay earlier this month, Union Jal Shakti Minister C.R. Patil maintained that India is prepared. “China can do whatever it wants; we are fully prepared. PM Modi is quite serious about it. Work will start,” he said.

NHPC officials have echoed the sentiment that the project is critical not just for energy security but also as a safeguard against potential artificial floods or water flow manipulation from the Chinese side. Once completed, the Upper Siang project would be the largest of its kind in India.

Hydropolitics in the Himalayas

As construction begins on the Chinese side, and delays persist on India’s, the geopolitical weight of the Brahmaputra has never been heavier. With no binding water-sharing agreement between the two countries, and with climate change already altering monsoon and glacier-fed systems, the need for diplomatic, ecological, and strategic caution has become urgent.

This is no longer just about megawatts and engineering. It’s a story of regional power dynamics, ecological fragility, and the lives of millions downstream who depend on the Brahmaputra’s natural flow.