NEW DELHI: India has never had a shortage of women in politics—at least on paper. From village panchayats to Parliament, reservation policies have steadily increased the numerical presence of women in decision-making spaces. Yet a harder question persists: does visibility translate into influence? Or has representation remained symbolic, while real power continues to sit elsewhere?

The distinction between reservation and representation is crucial. Reservation ensures seats. Representation demands voice, agency and impact on policy.

NUMBERS DON’T AUTOMATICALLY MEAN POWER

India’s 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, mandating 33 per cent reservation for women in local bodies, were a watershed moment. Today, women make up nearly half of all elected representatives in panchayats in several states. On the surface, this looks like a quiet revolution.

But research and ground reporting often reveal a more complicated picture. The phenomenon of “sarpanch pati”—where male relatives exercise power on behalf of elected women—has been widely documented in states like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Women occupy the seat, but decisions are made elsewhere.

Yet to stop here would be reductive.

WHEN WOMEN DO SHAPE POLICY

Take Chhavi Rajawat, former sarpanch of Soda village in Rajasthan. Educated and independent, she resisted proxy leadership and pushed for concrete reforms—introducing digital transparency, improving sanitation, and ensuring access to clean drinking water. Her leadership showed that when women have autonomy, outcomes change.

Similarly, in Odisha, women-led self-help groups have significantly influenced local governance. Under Mission Shakti, women representatives pushed policies focused on nutrition, livelihoods and social security—areas traditionally sidelined in male-dominated governance. The result wasn’t just participation, but a shift in priorities.

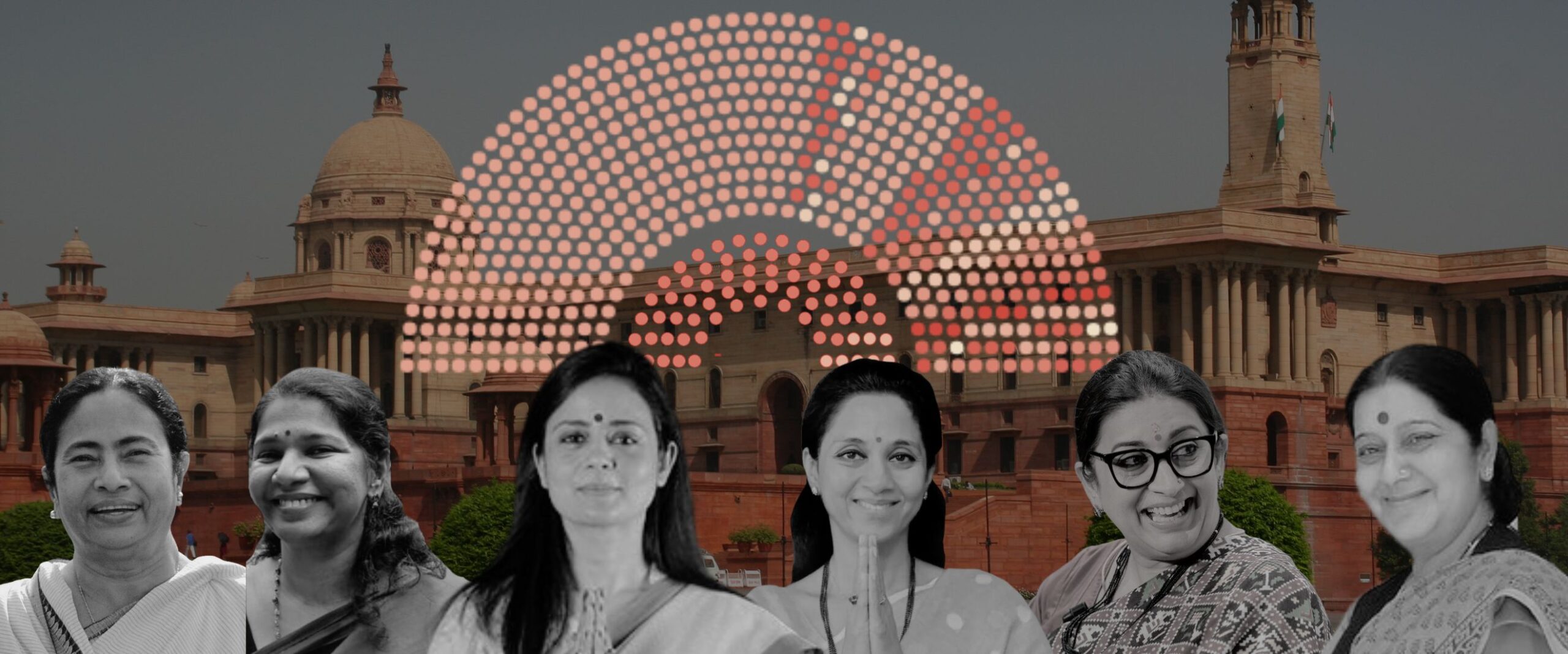

At the national level, the influence is uneven but visible. Former Union Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s tenure as Defence and Finance Minister challenged the assumption that women leaders are confined to “soft” portfolios. Meanwhile, leaders like Mamata Banerjee reshaped welfare politics in West Bengal through schemes such as Kanyashree, which reduced school dropout rates among girls and earned global recognition.

THE STRUCTURAL BARRIERS REMAIN

Despite these examples, women remain underrepresented where laws are framed. As of now, women make up less than 15 per cent of the Lok Sabha. The long-pending Women’s Reservation Bill—passed in 2023 but yet to be implemented—promises 33 per cent reservation in Parliament and state assemblies, but its delayed rollout has raised concerns about political will.

Even when women enter legislatures, they face symbolic obstacles: exclusion from informal power networks, gendered scrutiny, and the expectation to conform rather than disrupt. Studies show women legislators speak less in Parliament not due to lack of interest, but because of hostile environments and limited opportunities to lead key committees.

WHY REPRESENTATION STILL MATTERS

Critics often argue that reservation promotes tokenism. But evidence suggests otherwise over time. A landmark study by economists Esther Duflo and Rohini Pande found that villages led by women invested in more public goods relevant to women, such as water and sanitation, and altered societal perceptions about female leadership.

In other words, representation may not immediately transform policy—but it reshapes norms, pipelines and priorities in the long run.

BEYOND SEATS, TOWARDS SUBSTANCE

The real question, then, isn’t whether reservation works—but whether institutions are willing to support women once they enter. Training, protection from political violence, access to funding, and inclusion in decision-making forums matter as much as quotas. Reservation opens the door. Representation determines whether women are allowed to walk through it—and rearrange the room.

Until women influence not just who governs but how governance happens, India’s democratic promise remains unfinished. The challenge now is to move beyond counting women in power, and start listening to what they’re changing.