NEW DELHI: The soft tinkle of anklets has always carried more information than a footstep ever could. It tells you how close the wearer is, how deliberate her movement might be, whether the stride is hesitant, hurried or heavy with resolve. In Indian culture—and especially in Indian cinema—jewellery does not merely decorate the body; it speaks. Often, it speaks before the character does.

An anklet does not need to be seen to be understood. A faint chime can signal mischief or romance; a sharper, louder sound can announce authority or anger. Cinema, acutely attuned to sensory cues, has long used this sonic shorthand. In horror films, anklets frequently precede the apparition, heightening dread by allowing sound to arrive before sight. From the eerie silences and sudden chimes of Tumbbad (2018) to countless ghost stories across decades, jewellery becomes an instrument of suspense. The audience hears danger before it materialises.

But beyond fear, jewellery in Indian cinema functions as a psychological, social and emotional language. It conveys desire, loss, survival, rebellion and memory—often more eloquently than dialogue.

DESIRE, POWER AND THE EXCHANGE OF JEWELLERY

In Umrao Jaan (1981), one of Hindi cinema’s most lyrical explorations of desire and artistry, jewellery becomes an offering of surrender. When Nawab Sultan, struck speechless by Umrao’s poetic brilliance, removes his necklace and places it at her feet, the gesture is not transactional—it is devotional. The necklace stands in for words he cannot find, for admiration that borders on worship.

“Jewellery in films like Umrao Jaan or Pakeezah (1972) marks allure but also vulnerability,” says Dr. Usha Balakrishnan, curator and art historian. “They are objects of desire, but also tokens women exchange to survive.” In Pakeezah, the heroine’s jewels heighten her mystique, yet they also underline her precarious position—ornamented, admired, and trapped within systems she did not choose.

Designers continue this dialogue between ornament and narrative. “Sometimes, we describe our work as ‘costume drama meets subculture’,” says Aashua Singh of The Olio Stories, pointing to how jewellery design often straddles historical reference and contemporary attitude.

THE MANGALSUTRA: A SINGLE THREAD, ENDLESS MEANING

Few objects in Indian cinema compress as much emotional meaning as the mangalsutra. It is not just jewellery; it is identity. When tugged until it snaps, it enacts heartbreak with brutal efficiency—marriage, selfhood and security fractured in a single gesture. No monologue is required.

Classic Hindi cinema frequently used the slow unclasping of a necklace during suhag raat sequences as a stand-in for undressing. The camera lingers on fingers fumbling with clasps, transforming jewellery into a proxy for intimacy. The body remains unseen, but the message is unmistakable.

Yet the same mangalsutra can signify confinement as much as commitment. Contemporary films increasingly interrogate this symbol, showing women removing or refusing it as an insertion of autonomy.

JEWELLERY AS SURVIVAL CURRENCY

Indian cinema has long understood jewellery as a lifeline. Again and again, women pawn bangles, necklaces or nose rings to keep households afloat. From Radha in Mother India (1957) to innumerable melodrama across languages and decades, the art of selling jewellery is shorthand for desperation, sacrifice and maternal endurance.

“The paradox of Indian jewellery,” Balakrishnan explains, “lies in its ambivalence. As stridhan, it promised autonomy and financial security. As dowry, it became a burden. The same bangles that save can also shackle.”

This duality is central to how jewellery functions on screen. It can empower and imprison simultaneously, offering protection while reinforcing patriarchal expectations.

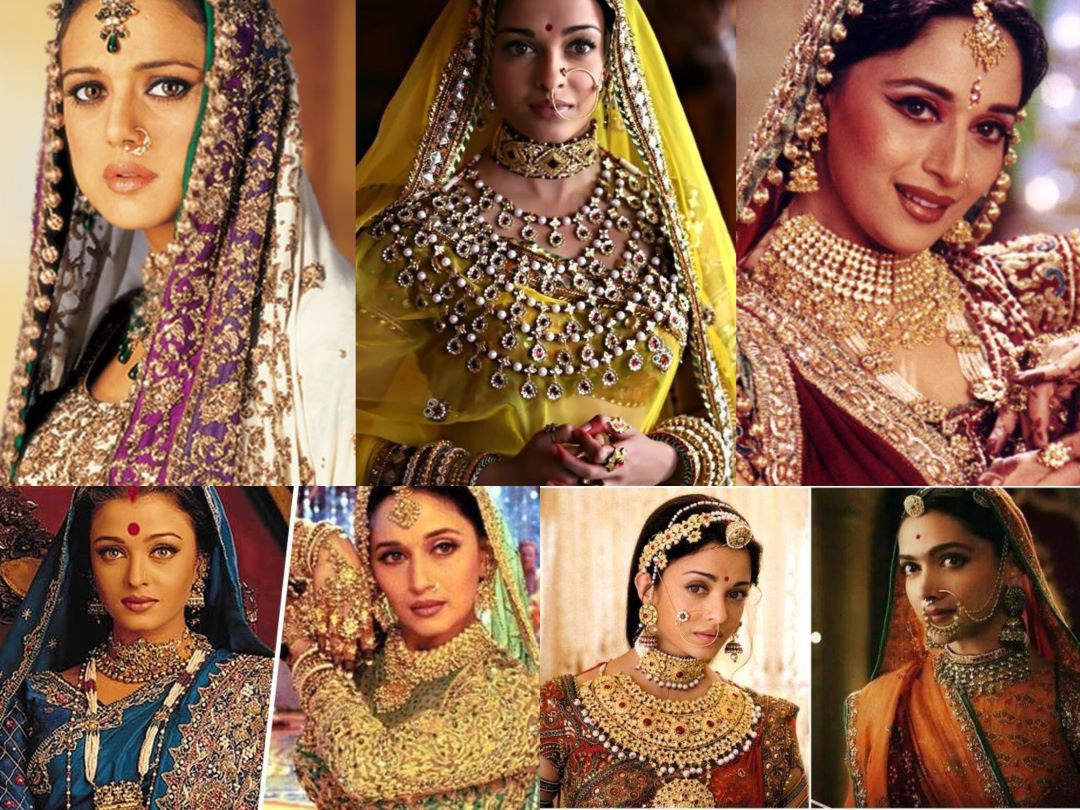

CHARACTER, CARVED IN METAL

Jewellery also scripts character with remarkable precision. Costume designer Eka Lakhani and jewellery designer Pratiksha Prashant, who collaborated on Ponniyin Selvan (2022), visited temples to study sculptures and ritual adornments. Each character’s jewellery was designed as a visual shorthand for personality, status and inner conflict.

This principle is equally evident in contemporary cinema. In Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani (2023), jewellery makes personality legible even before dialogue begins. Rocky, the flamboyant Punjabi protagonist, is draped in chunky gold chains and oversized rings—ornament as bravado, excess and emotional transparency. Rani, a cerebral journalist, wears chiffon saris and a clipped nose pin; delicate, restrained, but quietly sharp. Their contrasting ornaments mirror their class, temperament and worldview long before the script spells it out.

RITUAL, TRAUMA AND RECLAMATION

In Gangubai Kathiawadi (2022), jewellery becomes a rite of trauma and later, resistance. The nath utrai ceremony—the ritual removal of the nose ring—marks Gangubai’s forced initiation into sex work. The act strips her not only of jewellery, but of innocence and agency.

Later, dressed in white, Gangubai reclaims the same tarnished silver nath, wearing it as an emblem of pride. The ornament, once associated with violation, is transformed into a symbol of defiance—a refusal to be erased or ashamed. Jewellery here becomes a reclaimed narrative, worn against a society that denies dignity to sex workers.

JEWELLERY AS MEMORY AND TIMEKEEPER

Cinema also uses jewellery to bend time. In Veer-Zaara (2004), decades of separation are condensed into a single object: an anklet. Veer, after years in prison, pulls it from his pocket and kneels to clasp it onto Zaara’s foot. As she lifts her salwar, the camera reveals the matching anklet—worn all along.

No words are exchanged. The anklets, reunited, carry the weight of lost years, faith and unwavering love. Metal becomes memory. Jewellery becomes proof of endurance.

THE POWER OF ABSENCE

Sometimes, jewellery’s power lies in its absence.

In Piku (2015), the titular character wears no bangles, necklaces or nose rings. A young architect navigating work, caregiving and emotional exhaustion, Piku’s minimalism rejects ornament as shorthand for femininity, duty or desire. Her bare neckline and wrists signal independence—not rebellion, but refusal.

The absence of jewellery becomes its own statement, especially in a cultural context where adornment is often expected.