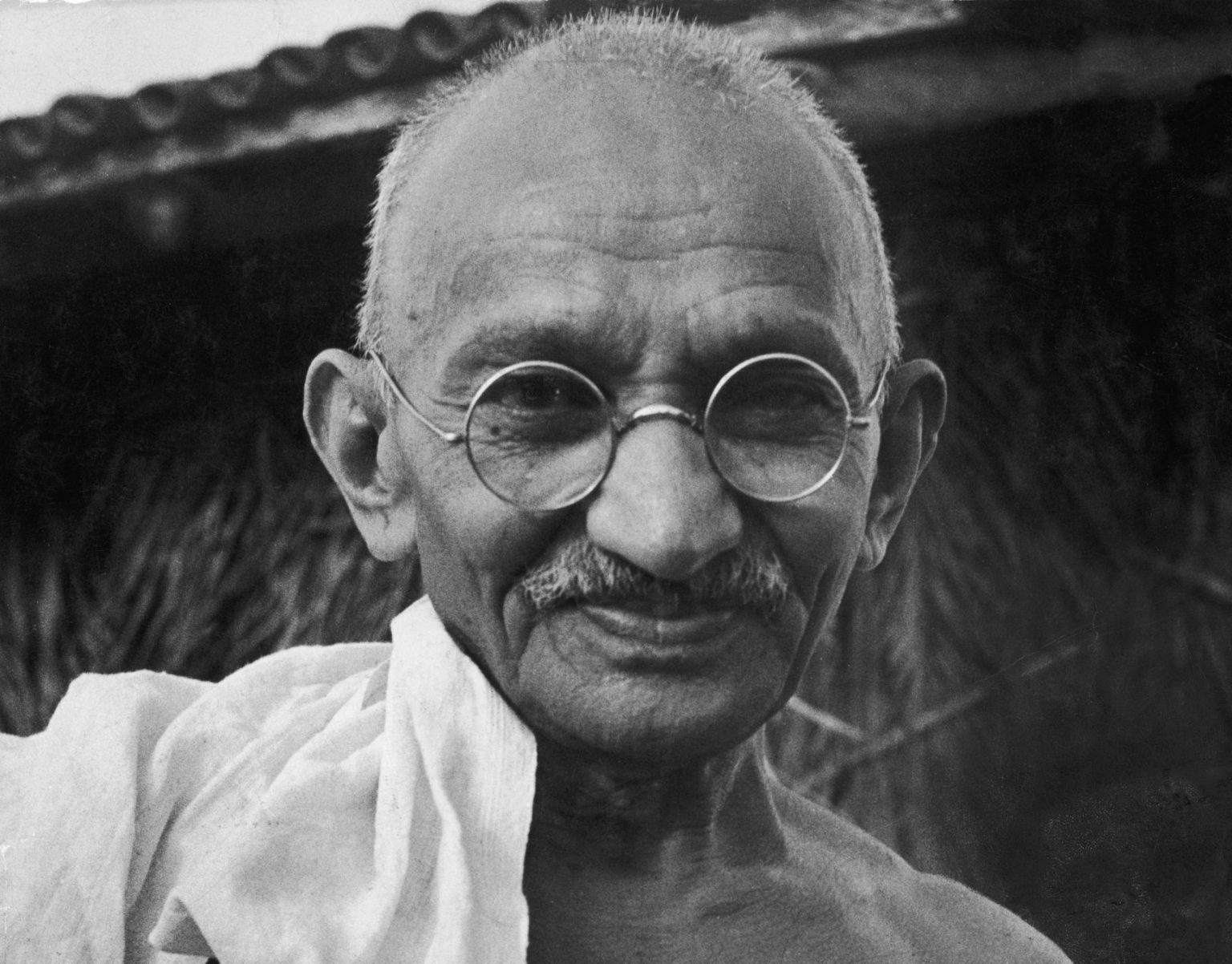

As Gandhi Jayanti approaches it’s time once again to reflect on the life and times of Mahatma Gandhi as depicted in articles, books and even cinema. Turning to the film ‘Gandhi’ which garnered as many as eight Oscars, Richard Attenborough the director shoots a scene etched in the minds of those who watched the film. It is a scene that takes place in Maritzburg, South Africa where the young barrister is thrown off a train with his luggage despite being in possession of a first-class ticket. It was a seminal event in his life with far reaching consequences. What happened next as far as his journey was concerned is much less well known.

The assumption is often made that Gandhi must have boarded another train in the second or third class in order to reach his destination. It is also assumed by many that he did not suffer any further insult or injury after that traumatic episode. This second assumption is simply not true. Gandhi was to suffer a another, yet more grievous physical assault upon his person, and was subjected to even greater abuse and humiliation.

After Gandhi was thrown off the train, he had to somehow reach his destination and so he boarded another train at Charleston, after buying another ticket. This time though he was not permitted to take a seat with the other white passengers on account of his colour. It did not matter that it was not a first-class compartment. A white train official forced him to sit next to the train driver. Gandhi was unhappy with this clear and rank discrimination but nevertheless swallowed the insult.

After a while this official wished to smoke a cigarette and for this purpose, he came into the section where the driver was sitting and desired to occupy the seat that he had previously asked Gandhi to sit on. He took a dirty piece of cloth from the driver, spread it on the footboard and asked Gandhi to sit on it. This suggestion was however completely unacceptable to the young lawyer. As the Mahatma writes in his autobiography: ‘The insult was more than I could bear. In fear and trembling I said to him: “It was you who seated me here although I should have been accommodated inside. I put up with the insult. Now that you want to sit outside and smoke you would have me sit at your feet. I will not do so.”’

The train official is enraged at what he perceives to be rank insolence and a challenge to his authority. ‘As I was struggling through my sentences,’ writes Gandhi, ‘the man came down upon me and began to heavily box my ears. He seized me by the arm and tried to drag me down. I clung to the brass rails of the coachbox and was determined to keep my hold even at the risk of breaking my wrist bones.’

Eventually, the Mahatma recalls in his autobiography it was eventually the passengers who came to his rescue at this stage and asked the train official to desist. Scowling, the train official leaves Gandhi alone, after warning him of untoward consequences once the train reaches its destination. Now if you compare these two episodes the second one involved greater injustice and humiliation for Gandhi. In the first incident, he was thrown off the train for rightfully not agreeing to move out of the first class; in the second instance the issue was not about the compartment being first class but he was simply not allowed to sit in the train with the other, white passengers. Moreover, in the first incident he was thrown off the train but in the second one he had his ears boxed. The assault was therefore far more severe. It is a measure of Gandhi’s grit and fortitude that he did not yield despite being assaulted.

Why did the screenplay writer and the director Richard Attenborough decide to exclude reference to the second incident in the film, and focus only on the first? Several explanations can be put forward in this regard. It can be argued, for instance, that Gandhi led such an active and eventful life that it was scarcely possible for him to include everything. The other thing is that as a metaphor the first incident may have held greater power. In his relative youth, Gandhi was thrown off a train in South Africa, but decades later, he would succeed, albeit with the help of many other contributors to the cause, in ending colonial rule and throwing the British out of India!

It’s also possible that Richard Attenborough realised that the second episode would arouse greater guilt in the white population and also enrage audiences in India. The ‘feel good’ part of the film would have been diluted if the cruelty of the colonisers was made too apparent. Western audiences sitting in movie theatres would shift uncomfortably in their seats. It would not do for the film to become too controversial in India either. After all, which community could stand seeing the Father of the Nation having his ears boxed by a white train official? Indians, especially, are an emotional people. Moreover, the co-producer of the film had persuaded then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to ask the NFDC to contribute ten million US dollars towards the initial financing of the film. Due regard had therefore to be paid to Indian sentiment.

How would the Mahatma himself have reacted had he come to learn of the selective exclusion of a part of his struggle if it had been for the aforesaid reason? It is of course a purely hypothetical question for the film was released many decades after his death. The peacemaker in him would doubtless have approved. The truth seeker, perhaps not.

(Rajesh Talwar is the prolific author of thirty-six books across multiple genres and has worked for the United Nations for more than two decades across three continents. He is the author of ‘The Boy Who Became the Mahatma.’)