Social media has been profligately used and vehemently accused by governments across the world even though most contemporary politicians owe their rise to the power of social media. There is ample evidence that social media is merely a tool and not an essential element of development yet no one can disregard this platform for being a congregation of noisy babblers that make governments uncomfortable. My first encounter with social media as a potential tool for getting things done was in 2006-7 during my research visit to Australia. Social media was just in its nascent stage of experimenting with its impact under digital media. In a bus ride to the Hawke Centre in Adelaide, an apparent racist behavior of the bus driver enraged the university community as the news caught fire through social media. The ABP news channel’s investigative effort triggered immediate police action against the offender. It was also time for the 26th Prime Ministerial election in Australia during which social media campaigns designed by an advertising guru Neil Laurence and ABP TV telecasts for Kevin Rudd of the Labour party presented the artful absentee as a lionized cynosure of all eyes.

It was incredible how this technology impacted the minds of people and directed their decisions to the desired end. Rudd could defeat the longest-serving Prime Minister John Howard who had sympathies from the media baron Rupert Murdoch, owning Sky News and several other channels on Australian TV. This demonstrated the power of social media over the rest of digital media. These Australian encounters inspired me to frame some fundamental arguments for my book A Critical Impulse to e-Governance in the Asia Pacific raising issues of power behind the new technology. These ordinary voices which rule social media are like the tawny outrageous ants which invade any castle of power yet are rarely identified due to their erratic cyber movements as formidable weapons. This fear of cyber world gorilla warfare goes behind most governments undertaking efforts to regulate and also enslave this technology.

Social media provides for an in-depth social interaction against one-way television communication. The government under its ‘Framework and Guidelines for Use of Social Media by Government Organizations’, defines social media as Social Networking sites such as FaceBook or MicroBlogging sites such as Twitter or any web or mobile-based platform that enables an individual or agency to communicate interactively for an exchange of user-generated content. The real driver of change is digitisation which converts content from analog to computer-readable formats and significantly increases communicative capacity on high bandwidth, higher fidelity, and the ability to easily integrate content into the internet. Social media is a subset of digital media that adds database capacity to communication by increasing ability to define and analyse human relationships. Its platforms give rise to alternative form of political campaigns in which a role for non-profits, crowd sourcing and citizen journalism lay strong claims to legitimacy of government actions and initiatives. ‘Howdy Modi’ and a few months later ‘Namaste Trump’ are campaigns that perfectly fit as byproducts of social media.

An interpretation of political events and social activity with power to define newsworthy-ness challenges established institutional loci of power. In achieving these roles social media technologies like Facebook, Twitter and blogs have rapidly emerged as one of the strongest weapons of contemporary governance in the last 16 years since the origin of Facebook in 2004. According to statistics provided by the Global Media Insight, India’s vigorous and unrelenting number of social media visitors has surpassed even the USA on Facebook (340m) and YouTube (225m) and stand at rank two and three on Instagram (80m) and Twitter (22m) respectively. Surprisingly, China doesn’t even feature in the world’s top twenty users of these most accessed social media sites.

The media industry stopped getting raw news in 2014 when Modi and on his instructions, cabinet ministers, and the whole of bureaucracy stopped communicating directly with journalists but dispensed actively on Twitter which became a single potent source of information from the government. Interestingly when the Planning Commission was disbanded in August 2014, media was caught by surprise as news was neither shared nor leaked from the Cabinet which was briefed about this change two days prior to the announcement. The Editors Guild of India was visibly upset as they considered Twitter and Facebook shouldn’t become news disseminators in a country with limited internet connectivity. They asked Modi to ‘enlarge access and engage more actively’ with journalists. The successful ‘Howdy Modi’ event of September 2019, with more than 50,000 audiences in a packed stadium in Houston brought Modi’s skills of courting the Indian diaspora to its best. This impassioned following to Modi’s charisma was well shaped by the social media as much as it was for Kevin Rudd.

When ‘Howdy Modi’ was taking place, the most approving as well as most critical voices against it came through social media especially micro-blogs on Modi team’s planned agreements for the giant size investors in the energy industry. Houston University headed by an Indian American social scientist fairly understood the irrelevance of such a big show as merely a puff of social media. Of the 31m Indian diaspora scattered across the world, an estimated 4.6m live in the USA, a number that was a mere 12,000 in 1960s. These were Indians holding not just rich American assets but status, education, and global exposure. It was relatively much easier now than in the 1960s for a non-profit organization, ‘Texas India Forum’ to generate around $ 2.5 million for the Houston event given the power of social media outreach. A nationalistic excitement behind the bonhomie splashed through the social media sites capturing Houston’s rousing endorsement of the Modi event.

An interesting fact of the communicative rationality of social media is its ubiquitous outreach. The same diaspora that cheered ‘Howdy Modi’ was soon found asking about the purpose behind this mega show. The fact sheet was spread out detailing the long list of bilateral and multilateral agreements on the card. Modi tweeted “Howdy Houston?” and a round table with 17 CEOs of energy companies worth $1 trillion during his prospective visit to the USA. Modi again tweeted, ‘It is impossible to come to Houston and not talk energy’. These tweets were a big energy booster to Indian companies aspiring to become stakeholders in the American energy business especially in the background of their annual energy purchase from the USA going as high as $4.5 billion. So, Petronet LNG an Indian company signed an MoU with a Houston-based oil upstart company Tellurian for their LNG project in Louisiana. Petronet got an investment opening of $ 2.5 billion in its LNG export terminal with rights over 5 million metric tonnes of LNG per year for 40 years. The Ministry of External Affairs and the Modi team was prematurely upbeat on their achievement as displayed in their tweets even though this agreement was to be finalized only by the 31st March 2020. As was the future, this single MoU signed in the USA could not materialise despite extending its timeline twice, and finally on 31st December 2020, the agreement expired. The hype on social media did prove as a momentary puff.

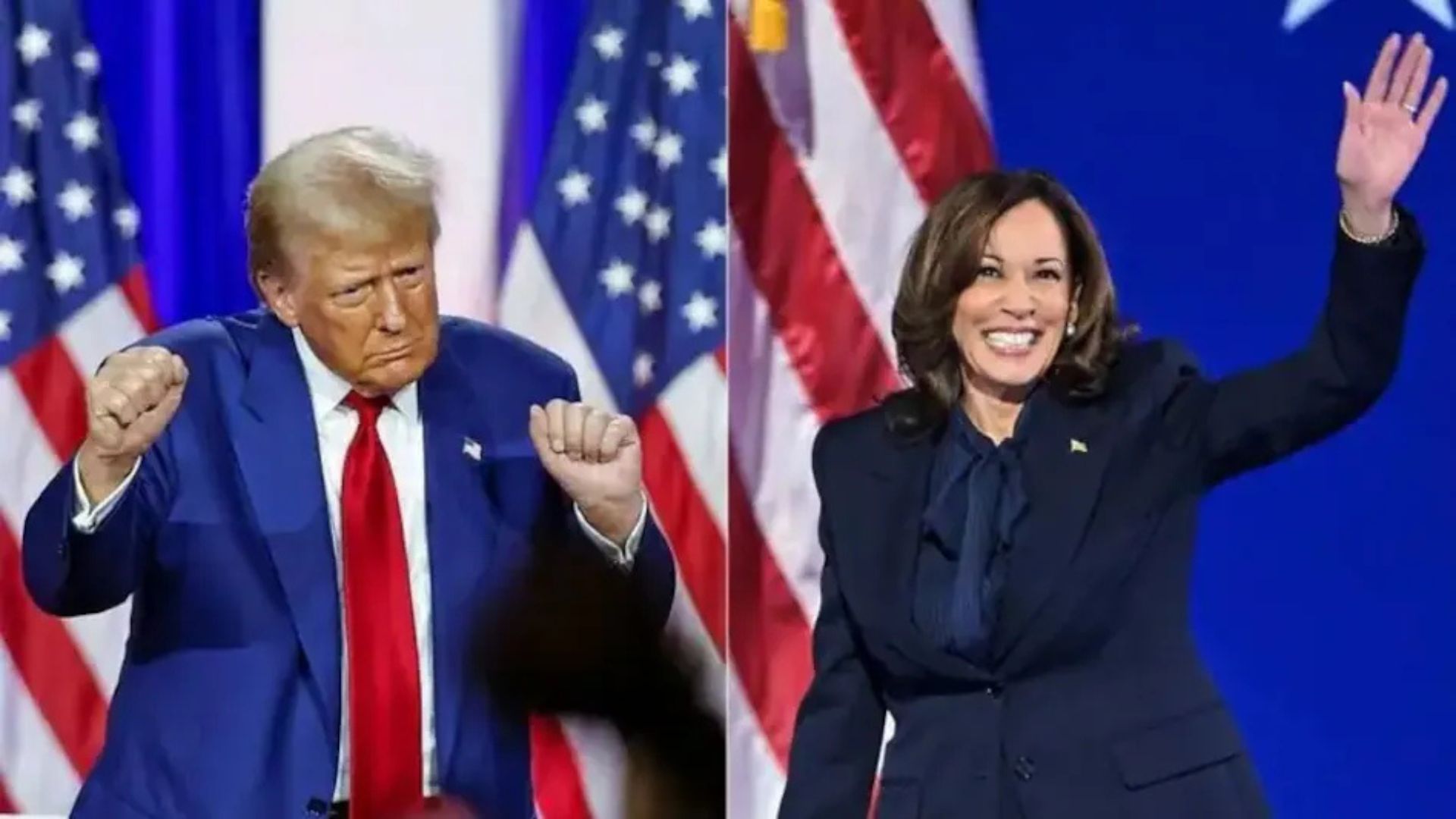

Six months after ‘Howdy Modi’, social media was being used again to engage people in a virtual show of strength. In Feb 2020 Trump visits India for a high-profile event ‘Namaste Trump’.The government spent more than Rs.100 crores to host him and his family for just 3 hours at the newly built Motera cricket stadium in Ahmedabad. This time, unlike their western counterparts spending the Indian diaspora’s money, the government-funded US President’s eventful visit. Even Trump was making public announcements on social media sites claiming to be greeted by more than 10 million people at the world’s largest cricket stadium in Ahmedabad without any idea that the total population of this city being 7 million only, there was a phenomenal error of estimation.

Social media gives no time for restraining oneself from turbulence striking within. Big leaders also get caught in this current and pay a heavy price. However, social media releases information that is denied even to a regular journalist such as information that a huge wall was being built to hide slums as Trump’s cavalcade arrives from the airport to the Motera stadium or in Agra, CM Yogi spent massively on an event with 3000 cultural artists and a stringent security arrangement for Trump and his family’s Taj Mahal visit or the cost of President Ram Nath Kovind’s gala dinner banquet in Trump’s honour or massive government arrangement for his family’s visits to several other places. While TV channels were incessantly debating with a muscle-flexing intimidation on what a great achievement the visit had been for India someone leaked to social media that Trump refused to sign a single agreement placed before him in Delhi but on the contrary earned a defence purchase deal of $ 3 billion from India. This amount worth of highly sophisticated military equipment has been left free by America in the hands of Taliban. Social media made the visit look so great, which it wasn’t. In a blog of the Atlantic Council a Washington based think tank, ‘while the visit was widely lauded by domestic media in India….the trip failed, however, to produce large or transformative agreements to advance the US-India strategic partnership, while laying bare troubling contradictions in the bilateral relationship.’

Social media is disturbing for dogmatic and liberals alike yet the world has reached a point of no return. Whatsapp and Facebook join people across the world, lost friends are discovered, parents and grandparents happily connect to those they may never get a chance to ever visit especially as national frontiers get more vulnerable to pandemics and wars. Modi was optimistic about this new digital technology in 2014-15 when he joined Instagram in November 2014, addressed the 18th National Conference on e-Governance through Twitter, and even joined enthusiastically the Chinese social media platform Weibo with his message, ‘Hello China, Looking forward to interacting with Chinese friends through Weibo’. After five years of raging global experience on these sites, Modi suddenly declared on 3rd March 2020 to quit his accounts. It appeared as a social media detox exercise for someone who has been through too much but as it later turned out that he was only offering it temporarily to celebrate inspiring stories about women on women’s day.

Social media has definitely become a battle field for the rogues who don’t wish to be seen otherwise but it has also become a site for first information report which the police rarely registers for those lower in hierarchies of power. The rising questions on accountability of proclamations made from Central government podiums, the integrity of enforcement and vigilance agencies, and official shielding of lynch and rape crimes by the upper castes has dipped reputation of the government to a new low. The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) issued a new set of rules on 25th Feb 2021 under the Information Technology Act 2000, called the ‘Information Technology (Guidelines for Intermediaries and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021’. This was done to prevent the misuse and abuse of social media and digital media platforms.

Regulating social media may be a complicated choice between accountability and a much-required autonomy of people. With an overload of variety and versatility, regimentation of social media may lead to misunderstanding of cultural attributes and cognition, mental and symbolic representations of reality in expressions and languages of people stuck in the periphery of governance. As the Internet Freedom Foundation fears, there might be more censorship through government’s oversight. In conclusion, the rules of social media should be revisited in the interest of accommodating more people and diverse anthropological expressions notwithstanding their legal accuracy and annoyance to the government in the interest of democracy and freedom of expression.

The author is president, NDRG, and former Professor of Administrative Reforms and Emergency Governance at JNU. The views expressed are personal.