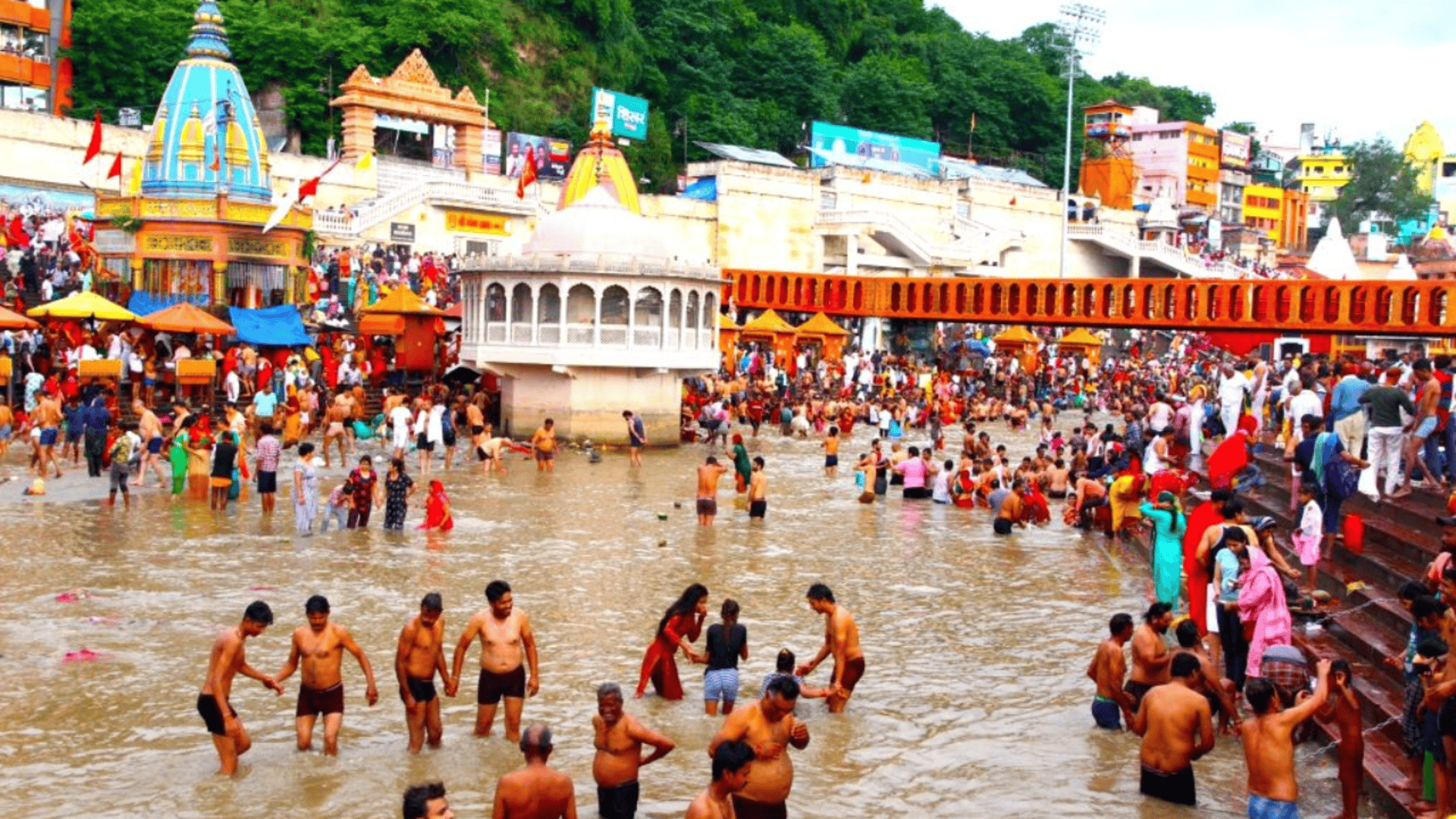

The death of an elephant in Kerala’s Palakkad district recently outraged the nation’s conscience. The autopsy proved she had consumed an explosive filled coconut, earlier believed to be pineapple, meant to scare off wild boars from eating crops. Whether it was a deliberate act of mischief or an accident remains to be ascertained. The pregnant elephant became the face of tragedy as she gave up life standing trunk deep in a river.

Sadly this is one side of the story. In a different district of Kerala, viz. Kannur, the government is planning to construct a wall at a cost of Rs 22 crore to shield elephants from Aralam Farm sanctuary raiding nearby villages frequently. Curiously, the fund is being provided by Kerala’s Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Development Department. In neighbouring Karanataka video clip of a school girl named Vismaya, from Sakleshpur taluka of Hassan district, went viral last November. She was seen appealing to Chief Minister B.S. Yediyurappa to protect their village from recurrent forays of elephants. In the last 10 years, 60 people have died in Hassan district in elephant attacks.

Loss of human life, property and crops are often reported in elephant depredation. Both elephants and human beings are falling victims to a conflict situation. This would be evident from the figures presented in Parliament in recent past. The tally of human casualty stood at 516 (2016-17), 506 (2017-18) and 452 (2018-2019) in manelephant conflict. The Central government provides ex-gratia payments in case of death/permanent incapacitation, grievous and minor injuries, and loss of property/crops, etc, in such cases. While human deaths seem to moderate the total compensation has varied 14.95 crore (2016-17), 18.21 crore (2017- 18) and 14.98 crore (2018-19). This was informed by Babul Supriyo, MoS, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, in the Lok Sabha (vide Unstarred Question No. February 7, 2020). A Task Force in 2010 found that two out of every three rupees spent on elephant protection in India deals directly or indirectly with elephant-human conflict.

Every year, on an average, one hundred elephants also die in India due to train accidents, electrocution, poaching and poisoning. The population of wild elephants in India as per last synchronised elephant estimation (2017) is 29,964. The next estimation is due in 2022. The figures of estimations in 2007, 2012 and 2017 point towards fluctuating elephant population. There has been a decline of elephant population between 2012 and 2017 from 29,391 (lowest estimate) to 27,321. The Arthashatra, Asokan pillar edicts and the Elephant Preservation Act, 1879 in colonial times speak of state’s concern for protecting elephants down the ages. A “Project Elephant”, on the lines of “Project Tiger”, has been in operation since 1991.

Almost 30 years ago Douglas H. Chadwick, the illustrious American biologist, author and photographer, tracked the condition of the elephants across Africa and Asia. In his book, The Fate of the Elephant (Penguin-Viking, 1992), he opines that it is at once discouraging and hopeful that India holds between 35% and 50% of all elephants in Asia. Discouraging because it shows how few elephants are left in the wild. The contemporaneous figure that Chadwick cites for Asian elephants is 35,000 and 55,000 besides 16,000 in captivity.

However, Chadwick had reasons to be hopeful at the same time. That India, despite her burgeoning population, could still hold between 17,000 and 22,000 wild elephants might reveal something very important about how to co-exist with those giants in an overcrowded world. India’s population is larger than entire Africa’s, but land size one-tenth. If three decades later elephant population has grown, in tandem with human demography, it shows India has not done a bad job.

Elephants have historically commanded an imperial status in India. They used to be part of regular army from the days of the Mahabharata to the beginning of Mughal era. During the British era, when hunting was legal pastime, elephants were used as mount. Princely states groomed elephants for peasantry. The post-colonial era came as catastrophe for the elephants both in Asia and Africa. This has little to do with end of imperialism and spread of democracy or rise of despotism. The postcolonial era everywhere was dominated by discourse of development even at the cost of environment. New urban projects meant reduction of forest cover, and consequential loss of natural habitat for the elephants. The illegal trade in ivory also took its toll on elephant population. Ajay A. Desai and Heidi S. Riddle in their study, “Human-Elephant Conflict in Asia” (2015), say that the estimated original range of Asian elephant had declined from nine million sq km to mere half a million sq km. The problem of wild elephant habitats attained serious proportions in the second half of the twentieth century. Desai and Riddle cites that forest cover in Sri Lanka declined from 44% in 1956 to 22% in 1988. Cambodia saw a rapid decline of forest cover in 73% in 1970 to 53% in 2000. In the same period Mynamar’s forest cover declined from 47% to 36%.

Elephants tend to migrate, seasonally or otherwise, from one natural habitat to another in search of food. The lean patch they pass through is termed corridor. The numbers of such corridors are on the rise as habitats degenerate and fragment. Between 2005 and 2017 the number of elephant corridors in India has gone up from 88 to 101, which describes a general trend. These elephant corridors enjoy no legal protection under the Wildlife (Protection) Act or the Environment (Protection) Act. Nor is the government in a position to secure the same by purchasing the entire real estate. The level of elephant-human conflict is more pronounced in the states like West Bengal, Assam, Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh than in the South.

The then UPA-II government had constituted a task force in 2010 on the elephants chaired by Dr Mahesh Rangrajan. The report of the task force titled “Gajah” advocated India to take a global lead in elephant conversation. The task force advocated that India should convene first ever International Elephant Congress with conclaves on science, culture and management that would lay down a vision for the next 50 years in 50 range countries of the world. Second, it also advocated exchange of ideas, expertise and good practices of managing elephant ranges. The report also advocated India proposing a United Nations Day for Elephants. It also proposed trans-boundary cooperation through an Asian Elephant Forum whereby India could cooperate with Bhutan, Nepal at the earliest and Bangladesh and Myanmar subsequently to achieve trans-border elephant landscapes.

The report felt there was a need to declare Asian elephant as India’s national heritage animal, and involving people in the campaign to save elephants. Sadly, the recommendations of the report are gathering dust in bureaucratic labyrinth. Will the killing of the she elephant in Kerala ignite the movement that “Gajah” envisaged a decade ago?

The author is a writer and independent researcher based in New Delhi. The views expressed herein are his personal.