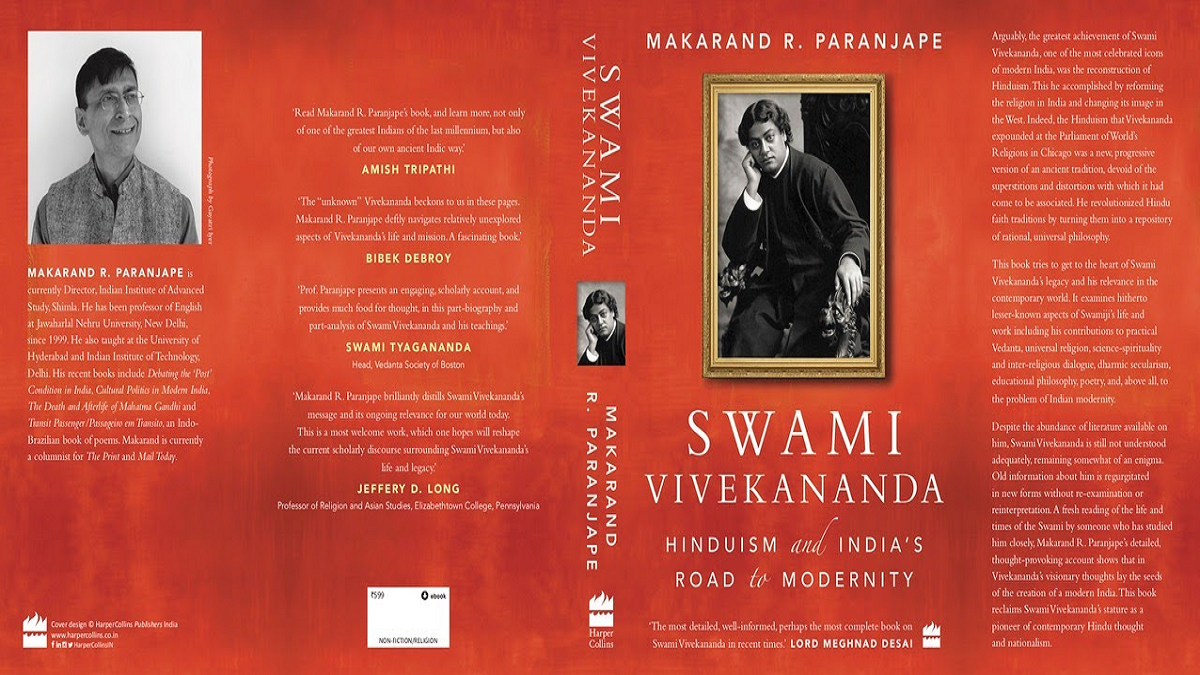

Call to Action

Swami Vivekananda, in his brief life of less than forty years, of which only the last nine were properly in the public sphere, made an extraordinary impact on India. He was able to rouse a defeated nation’s consciousness by restoring pride and dignity to its masses. In doing so, he followed in the footsteps of great reformers and leaders such as Sankara, Ramanuja, Chaitanya, and Guru Gobind Singh, traversing the length and breadth of the land to inspire, rejuvenate, and unite the people.

Education and Social Change

For such a wide-ranging transformation to occur, education, which is a key instrument of change, could not, of course, have escaped his notice. Yet, as we know, Vivekananda did not sit down to write a treatise on his educational philosophy. Instead, his views must be culled and inferred from his various utterances on the subject, usually parts of larger speeches or works.

Luckily, such a work need not be done afresh; at least a preliminary sketch of it already exists. In 1942, T. S. Avinashilingam compiled a book of Vivekananda’s words on education. Avinashilingam was in prison, having been jailed for his role the freedom struggle, when he performed this task. The context of his labour is, thus, not irrelevant. India was engaged not only in overthrowing British yoke, but also in a massive reconstruction of its society. There was hope that a new India would emerge glorious from the ashes of foreign domination and centuries of slavery.

Mahatma Gandhi, who sent a handwritten endorsement from his ashram in Sevagram on 22 July 1941 agreed wholeheartedly. Addressing the author as “Dear Avinashi,” he said, “Surely Swami Vivekananda’s writings need no introduction from anybody. They make their own irresistible appeal.” Avinashilingam’s method in this book is to extract key ideas and statements on education from Vivekananda’s writings, arranging them thematically.

The Meaning of Education What is education? The very first page of the compilation begins with one such foundational idea: “Education is the manifestation of the perfection already in man” (1). Here we see the summary of Vivekananda’s Vedic approach to the topic: each jiva or individual is nothing but the atma or the ever-perfect supreme Self. All of life, not just education, is the unfolding of that perfection already inherent in us. Education is thus not something that must be brought in from the outside but only the enabling of what is already implicit. A good teacher is a facilitator, inspiring and encouraging the pupil to learn, grow, and manifest the knowledge that is already within, as a tiny seed contains a gigantic tree. However, a lot of what passes for education, whether at home or in formal institutions like schools and colleges, only curbs a child’s creativity, seriously impairing its capacity to reach its fullest potential.

What follows is the emphasis on a positive pedagogy: “We should give positive ideas. Negative thoughts only weaken men” (5). For Vivekananda education was life-making, not life-destroying enterprise. Whatever weakens the pupil is bad, whatever strengthens good: “Infinite strength is religion. Strength is goodness, weakness is sin. All sins and all evil can be summed up in that one word: weakness. It is weakness that is the motive power in all evil doing” (42). That is why Vivekananda believed in inculcating positive thoughts and values in the people: “If you can give them positive ideas, people will grow up to be men and learn to stand on their own legs” (ibid). For Vivekananda, it was important to empower the weakest of the weak and the most neglected or degraded sections of society. Only a positive education could do that. Today, however, in the name of empowerment, we divide society and pit one section of the community against the other. Many of our universities are hotbeds of a negative politics which foments disharmony and conflict rather than solidarity and cohesion.

Thirdly, Vivekananda contends that education is the building of character, not merely the gathering or absorption of information. It is inculcating good values, such as will serve us for our whole lives: “Education is not the amount of information that is put into your brain and runs riot there, undigested all your life. We must have life-building, man-making, charactermaking, assimilation of ideas” (6). Here, assimilation more than information is stressed. To assimilate one good idea is better than knowing dozens of them but not making them a part of our lives.

Vivekananda is also very critical of what he considers wrong education: “Getting by heart the thoughts of others in a foreign language and stuffing your brain with them and taking some university degrees, you consider yourself educated” (7). For him, this is not education but only prelude to slavery. Rote learning and slaving thinking do not produce the kind of men and women that an independent country needs. Such “educated” graduates only become a burden on society, not even able to earn a decent living for themselves. They cease to do manual labour and expect the government to give them doles. Instead, Vivekananda says, “It is man-making religion that we want. It is man-making theories that we want. It is man-making education all round that we want” (8).

Methodology and Pedagogy

Now the question is how? Having clarified the main goal of education according to Vivekananda, which is “man-making,” Avinashilingam next gathers quotations on how it is to be achieved. The main method is concentration:

There is only one method by which to attain knowledge, that which is called concentration. … The very essence of education is concentration of mind. … From the lowest man to the highest yogi, all have to use the same method to attain knowledge.

Though these three sentences are taken from three different places in Vivekananda’s Complete Works, his emphasis on concentration is unmistakable: “The more the power of concentration, the greater the knowledge that is acquired” (9). For Vivekananda, concentration is the key to success not only in education, but in any endeavour: “In making money, or in worshipping God, or in doing anything, the stronger the power of concentration, the better will that thing be done” (9-10). Much of our thought-power, according to Vivekananda, is wasted; that is why we make mistakes (10), but a trained mind performs all tasks with a high degree of accuracy (ibid). Indeed it is concentration that distinguishes human beings from other animals. The results of concentration are almost miraculous: “All success in any line of work is the result of this. High achievements in arts, music, etc., are the result of concentration” (10). Unlike the Greeks, who applied their mind to mastering external nature, the Hindus, according to Vivekananda, turned it inward, to attain self-mastery. That is why it is in India that the science of concentration developed. Spiritual practices such as Raja Yoga greatly enhance the powers of concentration, which may be applied to secular realms of work and action too.

Vivekananda believed that the perfection of the instruments of knowledge, through a training of the powers of concentration, was much more important than the garnering of facts. True education would be the development of the faculties of the mind, which then might be used to gather facts as needed:

To me the very essence of education is concentration of mind, not the collection of facts. If I had to do my education once again, I would not study facts at all. I would develop the power of concentration and detachment, and then with a perfect instrument, collect facts at will.

No wonder, Vivekananda prescribes spiritual practices such as brahmacharya (chastity) and sense control to increase concentration: “Complete continence gives great intellectual and spiritual power necessary for concentration. Controlled desire leads to the highest results” (12). Once again, we see how today’s values are quite contrary to those that Vivekananda extols. Sense-indulgence, rather than sense-control, are promoted by today’s hedonistic culture. Whether in popular movies, television, or music indulgence rather than restraint is encouraged.

In addition to sensecontrol, Vivekananda also stresses on sraddha or devotion:

The idea of true Shraddha must be brought back once more to us. The faith in our own selves must be reawakened and then only the problems which face our country will gradually be solved by ourselves.

Without faith in our scriptures, masters, traditions, without reverence for the nation and its culture, it would be difficult to inculcate the right values or build character. Today’s education, in contrast, seems to encourage scepticism and disrespect for all that is ours, our country, culture, traditions, religions, and so on. But above all, Vivekananda wanted everyone to have faith in themselves: “First have faith in yourselves” (14) for “Mine also is that infinite ocean of life, of power, of spirituality as well as yours” (ibid).

For Vivekananda, education not only meant a development of character, but also of personality and leadership. Great leaders were those who had a magnetic personality, instantly capable of influencing others. We are all bundles of energy, Vivekananda averred, with a part of our energies used up in preserving ourselves; the rest of our energy was expended in influencing others (21). Actually, the whole world was but a force-field of such influence: “The man who influences, who throws his magic, as it were, upon his fellow-beings, is a dynamo of power, and when that man is ready, he can do anything and everything he likes: that personality put upon anything will make it work” (22). For Vivekananda, the “secret of all education” was to develop such a personality through the “science of Yoga” (24). Yoga had discovered the “laws” which could mould and build-up personality. In essence, “He who knows and controls his own mind knows the secret of every mind and has power over every mind” (26). Once again, self-mastery, as in the Upanishads, is seen as the key to the mastery of the world; only the svarat (one who rules himself) can be the samrat (he who rules all):

The utility of this science is to bring out the perfect man, and not let him wait and wait for ages, just a plaything in the hands of the physical world, like a log of drift-wood carried from wave to wave and tossing about in the ocean. This science wants you to be strong, to take the work in your own hand, instead of leaving it in the hands of nature, and get beyond this little life.

According to Vivekananda, Prophets and incarnations of the Divine hasten or quicken this process of growth and spiritual evolution (28).

What, How, Which

Given that Vivekananda’s was a gospel of strength and self-upliftment, physical education was extremely important. His ideal in his context was Mahavira (Hanuman), the great disciple of Sri Ramachandra, for whom no physical exertion or courageous deed was impossible:

We now mostly need the ideal of the hero with the tremendous spirit of Rajas thrilling through his veins from head to foot the hero who will dare and die to know the truth, the hero whose armour is renunciation, whose sword is wisdom. We now want the spirit of the brave warrior in the battle-field. … Make the character of Mahavira your ideal.

Vivekananda advanced the model of responsible masculinity. He wanted the softer, more effeminate aspects of our worship such as the flute-playing Krishna of Vrindavan, to recede in the background; instead, he wanted martial notes to be sounded once-again:

The Damaru and horn have to be sounded, drums are to be beaten so as to raise the deep and martial notes, and with “Mahavira, Mahavira” on our lips and shouting “Hara, Hara, Vyom, Vyom,” the quarters are to be reverberated.

That is why physical education was a must

First of all our young men must be strong. Religion will come afterwards. Be strong, my young friends, that is my advice to you. You will be nearer to Heaven through football than through the study of the Gita. You will understand Gita better with your biceps, your muscles, a little stronger.

Football over the Gita— such was Vivekananda’s message to the weak, the cowardly, and lazy.But Vivekananda also advocated a cultivation of the heart, of strong sympathy and fellowfeeling for the oppressed and downtrodden; mere intellectual learning was not enough. The purpose of true religion was to make us love our fellow-beings: “The intensest love that humanity has ever known has come from religion” (47). Thus, what we see is Vivekananda advocating the fullest development of personality, physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual; such was his integral idea of eduation.

Women and Masses

Finally, Vivekananda paid a great deal of attention to the education of women and of the masses. His tireless advocacy for women’s education is, once again, based on Vedantic ideals: “the Vedanta declares that one and the same Self is present in all beings” (62). Why, then, should women be denied education and condemned to ignorance? He invokes Vedic women rishis such as Maitreyi and Gargi, quotes from Manusmriti (“Where women are respected, there the Gods delight, and where they are not, there all work and efforts come to naught”), cites the example of the United States where women enjoy great liberties and rights, and declares, “The principal reason why our race has so degenerated is that we had no respect for these living images of Shakti” (63). Once again quoting Manu, “Daughters should be supported and educated with as much care and attention as the sons” (ibid), he wants “Female education should be spread with religion as its centre” (64). According to Vivekananda, chastity is the highest virtue that women must maintain and Sita is therefore the best role model for Indian woman: “The women of India must grow and develop in the footprints of Sita. Sita is unique. She is the very type of the true Indian woman, for all the ideals of a perfected woman have grown out of that one life of Sita” (64).

While such an emphasis would not sit well with today’s feminists, we must not forget that Vivekananda wanted men also to practice self-control and service. Along with other arts and sciences, Vivekananda wanted Indian women to be schooled in the art of selfdefence: “Along with other things they should acquire the spirit of valour and heroism. In the present day it has become necessary for them also to learn self-defence how grand was the Queen of Jhansi!” (68). By educating a woman, a whole family can be uplifted: “It is only in the homes of educated and pious mothers that great men are born” (66) and “If the women are raised, their children will by their noble actions glorify the name of the country; then will culture, knowledge, power and devotion awaken in the country” (67).

When it came the pitiable condition of the masses of India, the millions and millions of Indian reduced to starvation, illiteracy, and wretchedness under colonialism, Vivekananda’s heart bled:

My heart aches to think of the condition of the poor, the low in India. They sink lower and lower every day. They feel the blow showered upon them by a cruel society, but they do not know whence the blow comes. They have forgotten that they too are men. … My heart is too full to express my feelings. So long as the millions live in hunger and ignorance, I hold every man a traitor who, having been educated at their expense, pays not the least heed to them. … Our great national sin is the neglect of the masses and that is the cause of our downfall.

Vivekananda realized the urgent need to educate and uplift the masses. He was against the monopoly over learning by a few and advocated mass education: “The only service to be done for our lower classes is to give them education to develop their individuality” (69). The only way that the masses could be educated is through the mother-tongue; Sanskrit was too difficult, even though its study was important and should go on (70). Vivekananda wanted education to go to every home in the country.

He thought that wandering sannyasins and selfsacrificing men of religion could also impart secular education from door to door: “There are thousands of single minded, self-sacrificing sannyasins in our own country, going from village to village, teaching religion. If some of them can be organised as teachers of secular things also, they will go from place to place, from door to door, not only preaching but teaching also (72-73). Vivekananda’s method in this regard is to rouse the fellow-feelings of the elite for their less privileged brethren:

Do you feel? Do you feel that millions and millions of the descendants of gods and of sages have become nextdoor neighbours to brutes? Do you feel that millions are starving to-day, and millions have been starving for ages ? Do you feel that ignorance has come over the land as a dark cloud? Does it make you restless? Does it make you sleepless ? Has it gone into your blood, coursing through your veins, becoming consonant with your heart-beats? Has it made you almost mad?

Here, Vivekananda takes the idea of collective responsibility to another level. He shows us how inhumane and callous we have become, how selfish and self-centred, with no care or concern whatsoever for our less fortunate countrymen and women. What can we do to improve their condition? We can help by bringing education to them: “Who feels for the two hundred millions of men and women sunken forever in poverty and ignorance? Him I call a mahatman who feels for the poor. Who feels for them? They cannot find light or education. Who will bring the light to them who will travel from door to door bringing education to them?” (76).

From this overview it is clear that Vivekananda did not distinguish too much between religious and secular education, considering them both to be interrelated and part of a holistic process of unfolding the potentialities already inherent in us. The ultimate goal of education was, of course, to manifest the perfection that we are all heir to by virtue of our being Divine Selves. Such a realization would lead to mastery, courage, fearlessness, and, ultimately, liberation.

Education, therefore, was not merely the imparting of information, but characterbuilding, for which positive thoughts and reinforcements were the only prescription. Good habits and values would help build character. For the powers of the mind to be development, concentration was the key. And yoga was the science of concentration. All students thus had to be yogis. Personality development was also a part of education; for to influence others personality was more important than learning. The way to develop one’s personality was by cultivating self-control and the restraint of the senses, especially brahmacharya or continence. Such restraint was recommended both to boys and girls. The best way of to educate was through personal example. That is why close contact with the guru was essential for the flowering of the student. Both gurus and sishyas or teachers and students need to live up to the highest ideals of the land. Education was meant not only to develop character and personality, but to produce leaders. Such leaders had to be strong and able physically, deeply compassionate and engaged emotionally, in addition to be mentally competent and spiritually advanced. An all-round, integral approach was therefore required.

Finally, Vivekananda believed that the education of women and the common masses of India was absolutely necessary for the transformation of the country. If for men, Vivekananda offered Hanuman (Mahavira) as an ideal, for women he proposed Sita, a model of chastity, patience, suffering, and courage. To educate the masses, he prodded and inspired the elites to do their bit rather than being selfish and uncaring. Without deep sympathy and fellow-feeling for the suffering masses, no privileged or educated Indian could help his country. In conclusion, Vivekananda’s views on education were wide-ranging and radical. If implemented, they are bound to result in a great social transformation in our country. We cannot help wonder if the current education system is be headed in a different, if not opposite, direction from what he advocated.