The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), set up a working Group, under the chairmanship of Ishaat Hussain, seeking to assess the viability of establishing a Social Stock Exchange (SSE). The Working Group has recently submitted its report which describes in detail the possible modes of investment, listing mechanisms, instrumental layout, personnel changes, rules, and policies that will go into making SSEs a market reality.

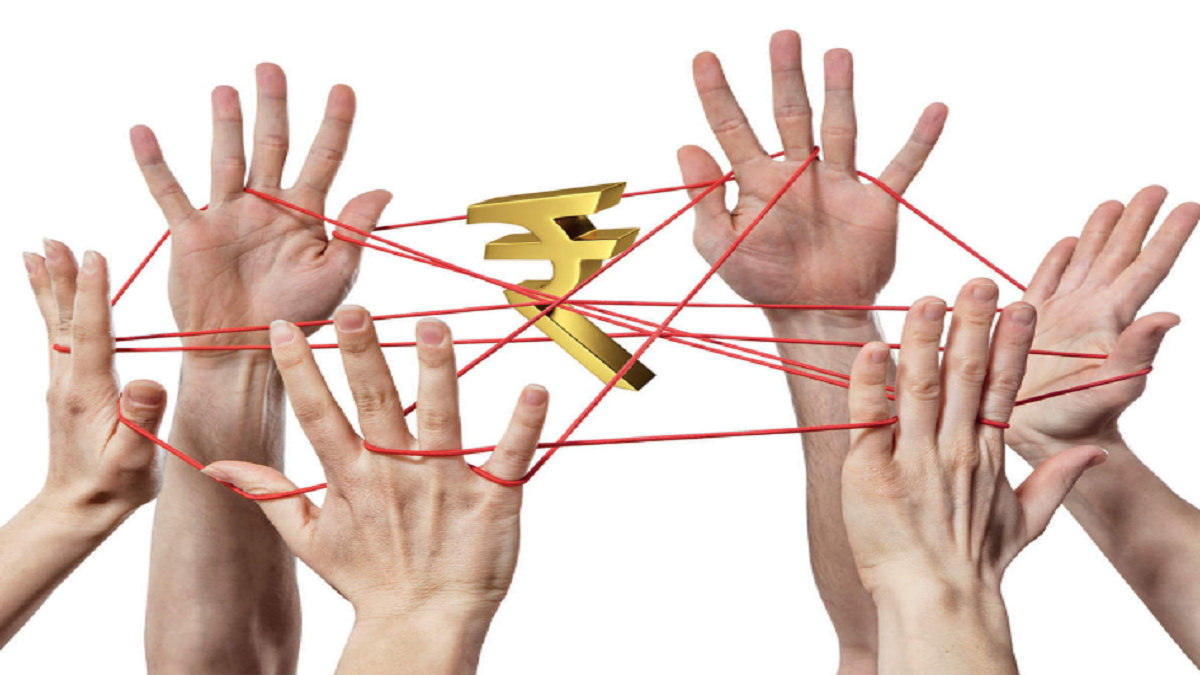

SSEs are listing forums that seek to serve as a bridge between the private sector and the non-profit sector, by channelling greater capital to volunteer organizations. In layman’s terms, it means that an individual can buy shares in a social enterprise, if they wish to contribute to the cause or mission they align with. At the outset, this may sound as an incredibly noble initiative. The biggest question that is posed is why can’t an individual simply donate to a charitable organisation of their choosing which aligns with the same social mission? Why does the need for commercialized forums such as stock exchanges arise in in promoting social goals? How would investing in non-profit organizations, prove different from donating for one? Predominantly, Non Profit Organisations (NPOs) in India are either set up as Societies, Trusts or Not-for-profit companies under Section 8 of the Companies Act. A sizeable chunk of fund raising for such NPOs is via donations, foreign contributions, CSR grants or from various government schemes.

As the Working Group Report notes, India is home to over 3.3 million nonprofit organisations, nearly one NPO for every 400 Indians. The Supreme Court, while hearing a petition in September 2016, mandated the government to audit and keep a check on the use of public funds, by NPOs. These entities, based on their nature, are required to be registered under law to obtain specific tax incentives, under Section 12A and 80G of the Income Tax Act, 1961. As per the CBI report filed before the Supreme Court, out of 3.3 million NGOs, only 0.3 million filed necessary accounts and expense statements with the ministries. This provides a brief overview of the gigantic number of NPOs at one hand, and the sparsity of their sources of funding, expenses, and management on the other hand. Effective social impact by these NPOs is largely dependent on adequate funding. Conversely, the ability to attract funds is contingent on evidence of impact and outcomes. Funders require bare basic information about financial reporting, governance structures and indicators of social impact. SSEs act as an efficient filter for organizations that create and report social impact, as well as follow best practices of financial reporting. Listing on SSEs would also necessitate proper registration and governance structures, providing an adequate cheque on financial activities of NPOs. As an added upside, enlisting NPOs on an accessible public forum, such as an exchange, accomplishes the task of public-visibility, crucial to attracting funds.

One of the glaring deficiencies in the report is its conscious reluctance to define ‘social enterprises’. This reluctance directly leads to the inclusion of FPEs for listing on the exchange as well, which seems hardly remedial in the effort to promote the social sector. Considering that the FPEs are inherently revenue-generating entities, it begs the question that at what point do you cap the absorption of this revenue by an enterprise to make the rest available for their social work. This remains conveniently unanswered in the absence of a definition to eke out the requisite social mandate of organizations.

The question of accountability is paramount while creating any mechanism through which to channel private money into the development of the social sector. In this regard, the Report devises a pay-forsuccess model. This system envisages a system of outcome-funding for the listed entities incentivizing investment based on the fulfilment of social welfare targets. The mandatory social-impact reporting requirements proposed for the SSE-listed bodies and their inclusion in the Information Repository (IR), generate increased credibility among social enterprises. These are two laudable steps in the establishment of a need-based self-reporting and auditing regime. The culmination of this robust framework lies in the guidelines of accreditation and creation of the NITI Aayog’s DARPAN. At last, the repeated directions of a tired old Judiciary to step up regulatory framework for such organisations have gradually taken off.

In the aftermath of COVID-19, the need for mobilising funds into the social sector to repair the widespread financial damages can’t be stressed enough. Impactinvestment, a concept that has been in financial parlance, is often regarded as a medium of attracting private equity capital into social development initiatives. A manifestation of this concept was seen in the world’s first SSE in Brazil (BOVESPA) in 2003. Within a year, the total investment in social shares at the exchange was R$1.1 million. The exchange had managed to help as many as 38 NPOs in their development work, thus gaining acclaim from the UN Global Impact for its contribution. Building on the same, the London SSE (NEX) devised its own form of listing. Organizations, whether for or without a profit-making intention were allowed to access financial markets and raise funds at the exchange, as long as their activities are focused on social and environmental missions. Such listing requires them to comply with a strict reporting standard in terms of their actions. The USA has no active SSE. However, there is a platform called Mission Markets, which connects high net-worth individuals and institutional investors with enterprises that are directly addressing social and environmental issues. As of now, it has 140 investment-ready offerings worth US$ 336 million. This affirms the fact that SSEs are in fact, tried-and-tested instruments in fund-raising. Also, they have efficient parameters of disclosure and accountability, via industry-mandated reportage which is essential for generating much-needed investor-awareness.

The United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP-FI 2005) Report emphasised that there is good evidence to suggest that Environmental and Social Governance (ESG) issues could have an impact on financial returns. To that effect, SSEs are promising undertakings with expected results (if properly allowed to scaleup) — the proposal to create a capacity-building fund worth Rupees one hundred crores, as suggested in the Working Committee’s Report. However, a heightened due-diligence framework of compliance is necessary before filing. The SelfRegulating Organizational (SRO) structure that has been suggested for day-today administration of the exchange must be improved upon by conferring the SRO, with greater adjudicatory powers to oversee and monitor malpractices.

Using private money to aid social development is going to be an established norm in the years to come. It is not desirable for the Government to always be expected to shell out taxpaying monies for their funding. Moreover, funding from the Government would be only a fraction of what could potentially be available from the capital markets. The lucrative quantum of funding attracts enhanced responsibilities of registration and compliance with audit/ reporting standards. As of now, NPOs continue to thrive in regulatory wilderness. For the sake of sociomoralistic commitment, it is essential to ensure that not a single penny attributed to the cause of the needy, goes unaccounted for. In an unending pursuit of Sustainable Developmental Goals (SDG), SSEs open a window to the gates of new-age philanthropy in an everdeveloping world of social growth.

Dr. Poornima Advani is Partner, The Law Point, a law firm with offices in Mumbai and New Delhi. She has served as the Chairperson of National Commission for Women.