The royals’ tryst with opulent design is historic. Anything they touch must be made in gold and encrusted with diamonds and precious stones. Fancy fables and larger-than-life coffee table books make you believe that they had emeralds for breakfast and diamonds for dinner.

Their link with European brands is amplified by global vested interests which make this uber luxe link work to their advantage, making present-day luxury-seekers feel like Maharajas when they invest in their brands. Fairy tales abound, like the famed Rolls Royce custom-built for Krishna Raja Wodeyar IV to shield his servants from the sun or the necklace Cartier crafted for the Patiala His Highness or the crystal chairs, tables, beds and sofas Maharana Sajjan Singh of Udaipur ordered from F. C. Osler in 1877. Such stories are found in abundance.

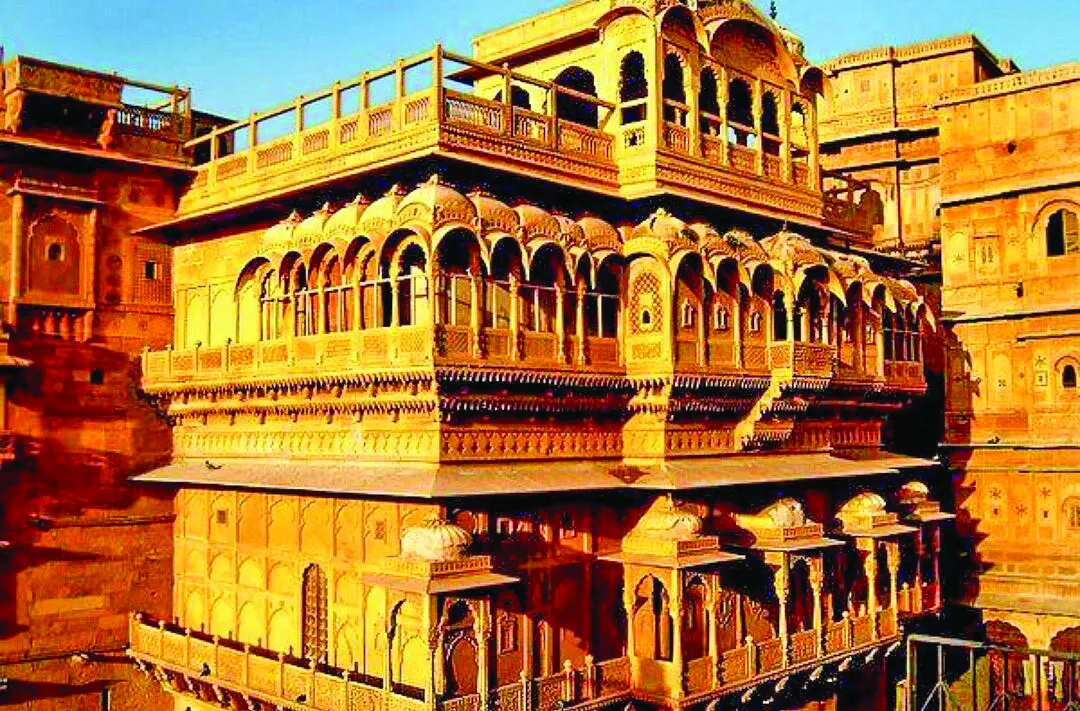

But even in this era of ‘Make In India’ and ‘Vocal for Local’, no light is ever thrown on the exquisite crafts that were made inside the Indian palaces by dexterous craftspeople who wove their magic in all they touched. From the finest robes in the softest hand-woven silks and chiffons, to the most exquisite silver artefacts and furniture, from precious ornaments to explicitly beautiful art and architecture – the royal families spent more time with their master craftsmen than they did in European ateliers, each one devising a design vocabulary that became a synonym for their legacy.

Every family dedicated a gracious part of their palace to a studio or atelier, that they called the kaarkhana. In these well-heeled spaces, artists, weavers, embroiderers, beaders, ornament makers, goldsmiths and silversmiths, all worked to make for the Maharaja and the Maharani anything they desired. Be it a Kinkhwab they might have dreamt of last night, a sculpture that they have a whim for, or a piece of jewellery they wish to adorn at the next auspicious occasion. These kaarkhanas developed a school of design deeply linked to each family’s history and heritage.

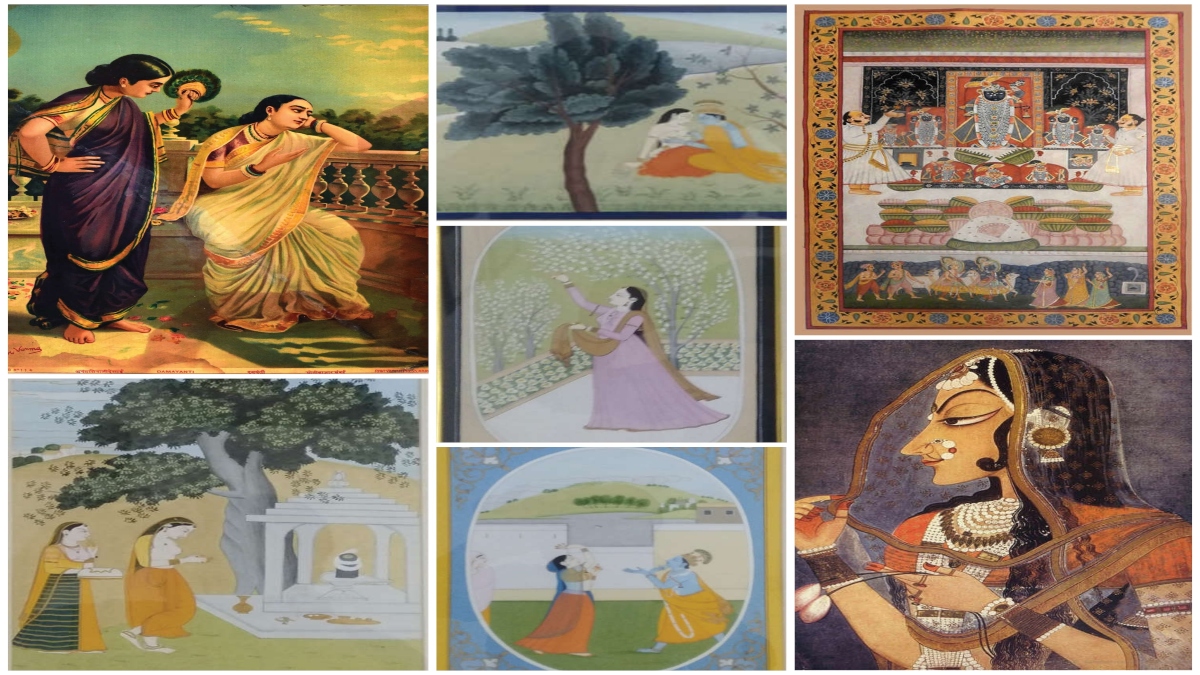

Patronage for art within these studios was legendary. Every Maharaja patronized a master artist who personified a distinct school of art, often synonymous with the region. The erstwhile royals nurtured in their courts a battery of artists who spent their entire lives either chronicling the queen and the king’s glorious lifestyle through art or representing the devi-devtas they bowed before.

Miniature art played the role that photographs do today: recording historic moments. Women in the palace were painted sitting next to a slender lotus, as beautiful as the proverbial flower. Conquests at war became the subject of a series of miniatures. The royal family often became a doting subject for portraiture, while the praja was seen floating around them, a reflection of their poetic beauty.

However, there were certain Maharajas who went down in history for their patronage and support of master artists who took their respective schools of art to the greatest heights. One of the most well-known among them was Maharaja Savant Singh of Kishangarh, under whom the miniature artist Nihal Chand flourished, devising his own style of miniature art that glorified the royal family’s beloved deity, Lord Krishna. In Rajasthan, where paintings with delicate detailing, a vibrancy of colours and a hint of gold and precious stones flourished, Nihal Chand, a surdhaj Brahman, started his artistic career at the age of fifteen. His palette consisted of rich reds, white and greens, with a range of greys and black. He received training in the local styles from the masters. He is believed to have been the one to initiate Bhakti paintings in the Kishangarh school.

However, the most famous among his (attributed) works is the jharokha bust portrait of Bani Thani, often referred to as the Indian Mona Lisa, which incorporates all the unique qualities and exaggerated features of this school, such as the large lotus-shaped eyes with arched eyebrows, and a pointed nose and chin. His other notable work, Godhuli Vela (The Hour of Cowdust), now showcased at the National Museum, depicts a tall blue-coloured Krishna with an hourglass waist.

The Gaekwads of Baroda have also left deep imprints on the cultural and socio-economic landscape of the city of Baroda. Under the late HH Sayajirao III, the state saw rich patronage given to art. His gracious support of Raja Ravi Varma, who created his studio within the premises of the Lukshmi Vilas Palace, is the most famed instance of his patronage.

It started in 1881, when Sir T. Madhavarao, the British Regent of Baroda, decided to invite Ravi Varma to paint the ceremonial portrait of Sayajirao III. Once in Baroda, Ravi Varma was welcomed as a privileged guest and all facilities were extended to him. The various assignments from the Gaekwads brought him much fame. Several of his best paintings were created in Baroda. The paintings depicting Nala and Damayanti, Radha and Madhava, Arjuna and Subhadra, Bharata, Shantanu and Ganga, Shantanu and Matsyagandhi were produced in this period. Many of these are on display today at the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery and the Maharaja Fateh Singh Museum.

The hill kingdoms of Kashmir, Chamba and Kangra brought the simplicity of the mountains in their form of miniatures too. The Kangra Kalam combined Mughal influences with the simplicity of the local artists who were greatly inspired by the atmosphere of the hills. The artistes adopted as their primary theme the eternal love between Radha and Krishna. This style reached its zenith during the reign of Maharaja Sansar Chand Katoch, who was a great patron of Kangra art. An ardent devotee of Krishna, he used to commission artists to paint subjects based on the love and life of Krishna. Under his patronage emerged the great artist Nainsukh whose works personified the ethereal light of hill art.

According to B.N. Goswamy, a leading scholar on Nainsukh, «devices and mannerisms associated with Nainsukh include: a preference for uncoloured grounds; shading through a light wash that imparts volume and weight to figures and groups; a fine horizontal line that separates ground from background; a rich green in which his landscapes are usually bathed; a bush with flat circular leaves that he often introduces; a peculiar loop of the long stem of a hooka; and a minor figure often introduced in a two-thirds profile.”

Nainsukh’s miniatures went on to embody distinctive features of Pahadi art. The verdant greenery of the landscape, brooks and springs were recurrent images. The colours used in the compositions were extracted from minerals and vegetables and possessed an enamel-like lustre. Through his work, Nainsukh, master of this style, introduced a distinctive vocabulary in the realm of Pahadi miniatures, which combined Mughal elements with personal innovations.