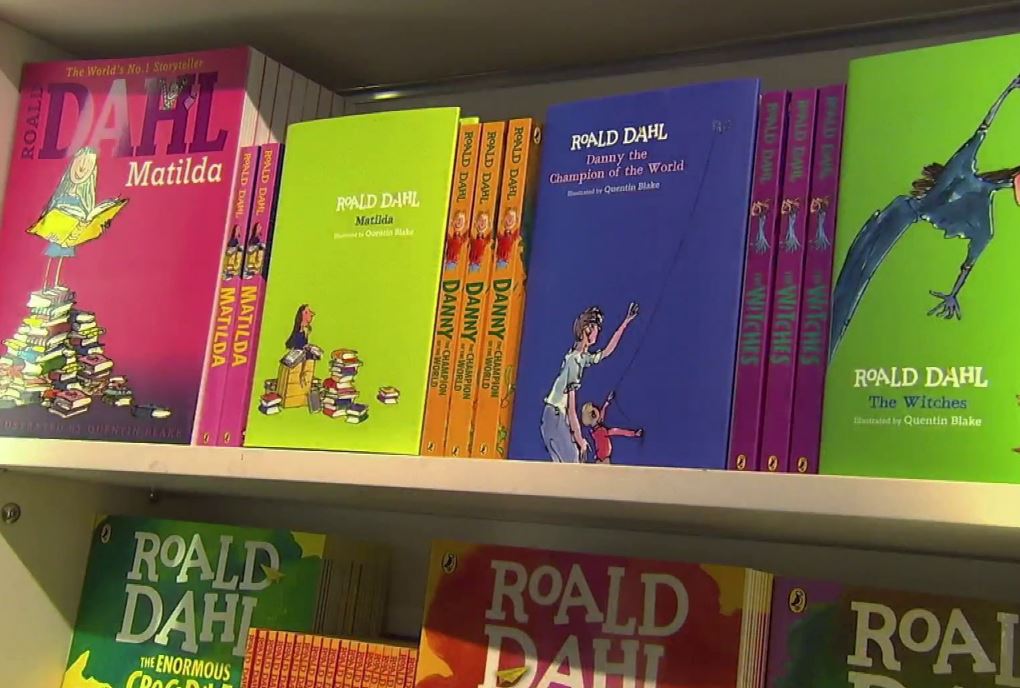

A fair amount of controversy was generated some weeks ago in respect of the proposed editing of several works written by notable children’s book author Roald Dahl. Mr Dahl, it was argued by his publisher, often used language that could potentially foster prejudice in children instead of inculcating good values. To take only one such instance, the author was overly fond of smelly, fat female villains. Such writing wasn’t sensitive to the feelings of overweight people or politically correct, argued his publishers. Ranged on the other side numerous writers and critics strenuously objected to such editing arguing that what the publishers were doing was tantamount to posthumous censorship of an author who, while he was still alive, insisted that his editors not change one full stop or comma without his express permission.

An argument was also raised that this could, potentially, be the beginnings of a new kind of censorship reminiscent of communist regimes. A communist regime might even quarrel with the choice of Charlie in Dahl’s famous ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,’ as being too royal sounding a name, especially in light of the recent ascension of Prince Charles to the throne. Wouldn’t it be better to have a more proletarian name? Chocolate itself was a bourgeois product. Such hypothetical censors could demand that the text be examined to ensure that the workers in the chocolate factory received a fair wage? In the realm of literature, where does censorship begin and where does it end?

Mr Dahl was the recipient of numerous prestigious literary awards. A question arises here. So much fuss is being made about Dahl’s work but correspondingly few questions are asked in respect of the Nobel Prize for Literature awarded in 1952 to Winston Churchill, a racist bigot if ever there was one. A small sampling of his quotes below will serve to illustrate the veracity of such an assertion.

In respect of Africans, he stated that ‘he did think that black people were not as capable or efficient as white people.’ Closer home, on the demand for Indian independence he believed that ‘if independence is granted to India, power will go to the hands of rascals, rogues, freebooters; all Indian leaders will be men of low calibre and men of straw.’ Indians, to him were ‘the beastliest people in the world, next to the Germans.’ Gandhi, for him, was a ‘malignant subversive fanatic.’ He also made remarks such as: ‘I hate people with slit-eyes and pig tails. I don’t like the look of them or the smell of them.’ Those who campaigned against colonialism were branded by him as ‘savages with ideas.’

Churchill’s racism should have been ample reason to disqualify him from consideration for the world’s preeminent literary prize. He also did not deserve it on the merits of the material in question. As pointed out by Madhusree Mukerjee in her excellent book ‘Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War 11’ Churchill’s view of history was that it was driven by great white men such as himself. According to British historian David Reynolds his work on World War II often ‘fell victim to selective memory.’ Lord Moran remembered events differently wondered: ‘Could it be that he had come to believe what he wanted to believe?’

The gravest omission in Churchill’s massive six-volume history of the war is that there is hardly a word in it about the Bengal Famine that took millions of Indian lives. A famine for which Churchill bore direct responsibility and which had led Shashi Tharoor to suggest that he deserves to stand besides Hitler and Stalin as one of the world’s mass murderers! It is true that Churchill won the Nobel for his writings prior to World War II but the criticisms still apply. As a matter of fact, Churchill himself was dismayed that he did not get the Nobel Prize for Peace, and accepted that the award for literature was undeserved. It’s almost as if powerful groups lobbying on his behalf were told by the Committee: ‘We can’t give it to him for Peace; he’ll have to settle for the one for Literature.’ Time and again the Nobel Prize has been accused of being too political, which hasn’t however prevented writers like Salman Rushdie from coveting the same. One of the major omissions referred to time and again is not awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Mahatma Gandhi. There have been individuals who have rejected the prize in the past such as the Vietnamese communist revolutionary Le Duc Tho and the French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre who refused because he didn’t wish to be institutionalised.

Editing Roald Dahl is by no means such a pressing issue as it has been made out to be. Be that as it may, what is far more important is that the curators of the literary world’s biggest prize, the Nobel Prize for Literature, render a fulsome apology to millions of readers who take the award at face value and allow it to influence their reading choices.

No precedent exists for revocation of the Nobel Prize. An apology can however be tendered. Better late than never, as the saying goes. The Committee has, in fact, time and again apologized for not awarding the prize to Mahatma Gandhi. It is about time that the Nobel Prize Committee issue an apology to the effect that it realises that its predecessors did not properly evaluate the candidature of Winston Churchill, and in view of his avowed racism as well as on the merits of the work in question deeply regrets its decision. In the unlikely event that the Nobel Committee is able to summon up the courage to issue such an apology, it will immeasurably enhance its credibility.

(Rajesh Talwar is the prolific author of 36 books across multiple genres, and has worked for the United Nations for more than two decades across three continents. His most recent book is ‘Trading Flesh in Tokyo: Nine Short Stories and a Play; Bridging Borders)