There is something inexplicable about the way babudom functions in India. If point A could be connected to point B by drawing a straight line, the intervention of an Indian babu will ensure that all the letters of the English alphabet are covered before the line reaches B from A. The direct fallout of this is the formulation of complicated rules and regulations that inconvenience the public and scare off businesses. In spite of “minimum government maximum governance” being the motto of the current government, the bureaucrats know how to bludgeon the public with a rules-hammer in the name of securing public interest. The latest directive from the RBI on “recurring standing instructions” to banks for online payments comes in this category.

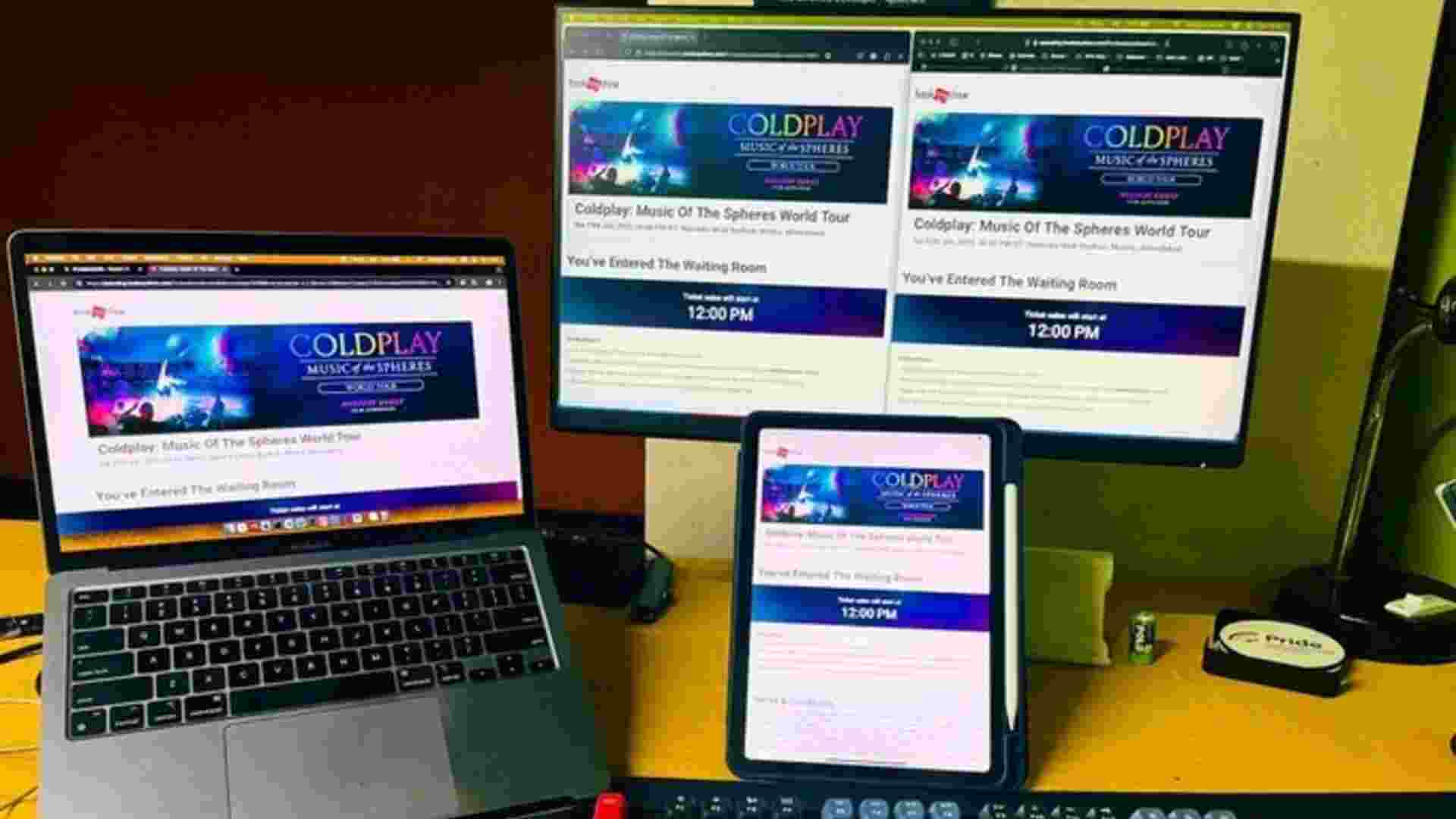

From 1 October onwards, all recurring or monthly payments to different services that are made through credit or debit cards, and are of the value more than Rs 5,000, need to be approved manually by the customer, instead of these getting automatically renewed through standing instructions given to the bank. And if the merchant that you take the service from has not yet made the changes specified by the RBI regulations, then the banks that have issued the credit or debit card, will block even a simple Rs 99 monthly payment to a music streaming service, until, in this case, the international merchant follows the new regulations, as this writer found to her surprise this week. Unless you have registered yourself on the merchant site, followed a two-factor authentication, renewed a payment of Rs 99 and received an e-mandate for subsequent transactions, you cannot renew your subscription. And if your merchant has not sorted out the matter with your bank, then your renewal will be declined. For recurring payments above Rs 5,000 this re-registering and two-factor authentication have to be done every month—month after month until the RBI has a change of heart and amends the rule. If this does not define tedious, what does?

This is posing a major problem particularly for those who subscribe to services provided by international merchants—this could be even monthly subscriptions to foreign publications, or a music/movie streaming service below the Rs 5,000 threshold. It will take some time before international merchants start following RBI regulations, not because they do not want to, but sometimes because they do not even know that such regulations have come into place. Until that time, all access to such international services/publications is blocked to the Indian customer.

We are told that the RBI has done this to protect us, customers, from online fraud and that by introducing these regulations they are giving us greater control over how our credit/debit cards are used online. But obviously, no one in RBI thought of how complicated implementing the regulations would be, and how much inconvenience these would cause to the customers.

According to experts, only about 50% of the banks are fully aligned with RBI regulations and it may take at least six months for the system to fall in place. But no one is being able to say how long foreign merchants will take to follow the RBI regulations, if at all.

Problems will also arise for web hosting platforms and the like whose recurring payments are generally above Rs 5,000 a month. There is speculation that this will make several foreign start-ups that focus on India, to look for alternate markets. If that ecosystem gets hurt, it impacts incomes in India as well, and thus hurts India’s prospects of attracting foreign investments.

To cut a long story short, RBI’s intention may be good, but the implementation is so bureaucratic that it does not inspire confidence in the process. And this has been the problem throughout with the Indian system, with—to give an example—the GST only now limping to normalcy, over four years after it was first implemented with several complicated and unfathomable rules and regulations. Sadly, all this is appearing to be a case of maximum government to achieve even bare minimum governance.