A two-year-old child in Meghalaya’s West Garo Hills district has tested positive for polio, a highly infectious and potentially fatal viral disease. However, this case is unusual as the infection was caused by a vaccine-derived poliovirus, a rare occurrence that can happen in some children with weakened immune systems.

What Is Vaccine-Derived Polio?

Vaccine-derived poliovirus is linked to the oral polio vaccine (OPV), commonly known as ‘polio drops’. The OPV contains a weakened version of the poliovirus, which is generally safe and effective in preventing polio. However, in rare cases, this weakened virus can cause the infection itself, particularly in children with compromised immune systems.

According to Dr. T Jacob John, a former virology professor at Christian Medical College Vellore, vaccine-derived infections can occur in two ways:

1. Reversion to Virulence: Sometimes, the weakened virus in the OPV can continue to circulate among children, gradually regaining its ability to cause severe infection as it spreads.

2. Chronic Infection in Immunodeficient Children: In children with weak immune systems, the weakened virus may remain in the gut for an extended period, slowly regaining its strength and eventually leading to severe infection.

In the case of the child from Meghalaya, it appears that the weakened virus in the vaccine replicated in the child’s gut over time, eventually triggering the infection.

Have Vaccine-Derived Polio Cases Occurred in India Before?

India’s last case of wild poliovirus, the naturally occurring form of the virus, was reported in West Bengal’s Howrah district in 2011. Since then, India has been declared polio-free, with no wild polio infections reported since 2014. However, cases of vaccine-derived polio have continued to emerge.

For instance, in 2013, an 11-month-old child in Maharashtra’s Beed district, who had an immunodeficiency, died due to vaccine-derived polio. Other cases have been reported across the country, with the most recent one before the Meghalaya incident occurring in Kerala last month.

These cases, while concerning, do not affect India’s polio-free status. Only the detection of wild poliovirus would jeopardize this status.

Preventing Vaccine-Derived Polio: A Balancing Act

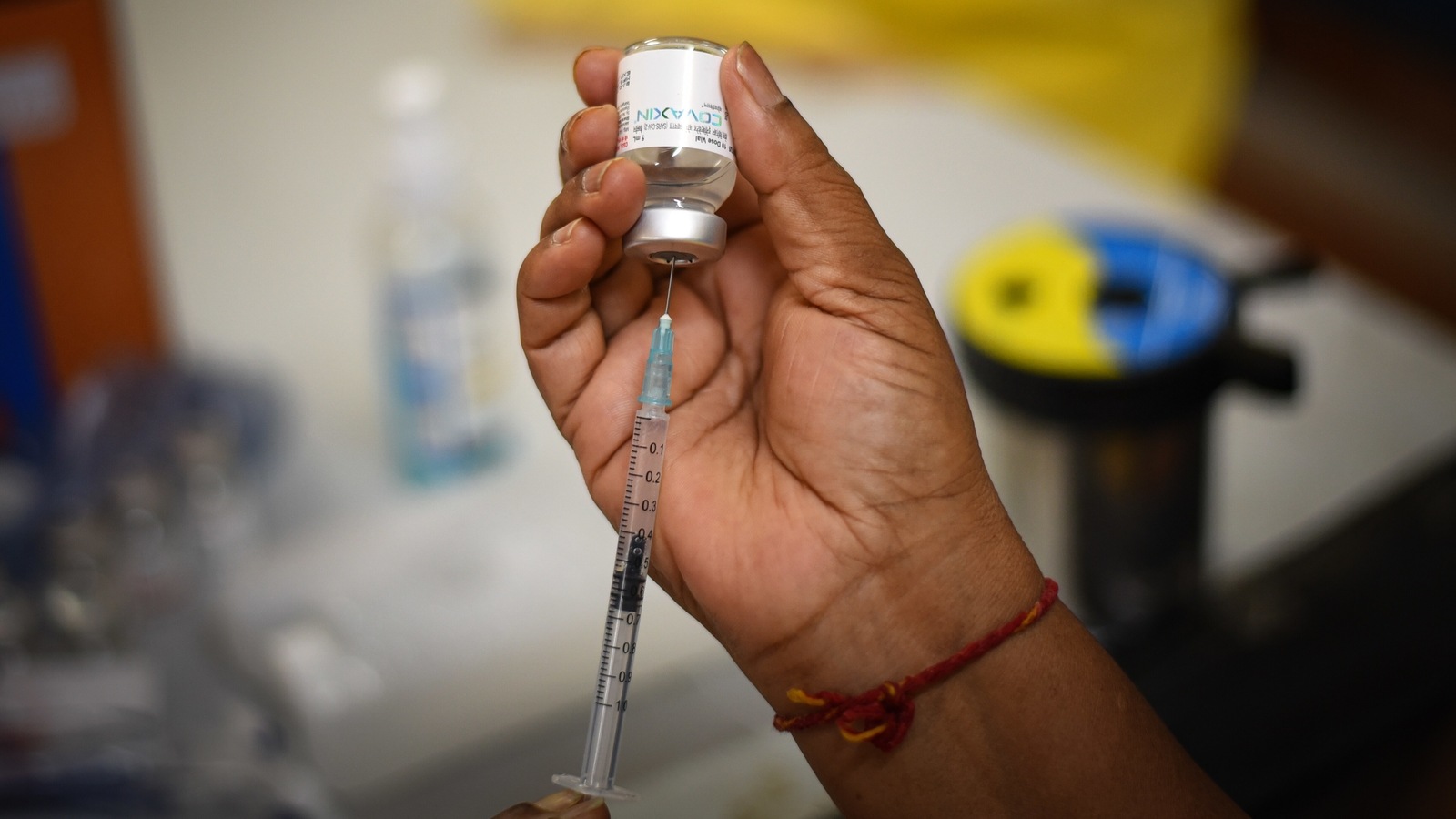

The oral polio vaccine (OPV) has been instrumental in the global effort to eradicate polio. Its ease of administration has made it the cornerstone of vaccination campaigns in many countries, including India. However, the risk of vaccine-derived infections has led some experts to recommend switching to the injectable polio vaccine (IPV).

The IPV is administered as an injection and does not contain live virus, so it cannot cause vaccine-derived polio. However, it has its own limitations. The IPV does not prevent the spread of the virus from one person to another, and it requires trained personnel to administer, which could lower immunization rates.

In India, both OPV and IPV are used. IPV is given during routine immunizations, while OPV is administered during Pulse Polio Days, a key part of the government’s universal polio vaccination campaign. However, according to Dr. John, India is using IPVs “sub-optimally,” typically giving only one IPV shot compared to three shots and one booster in countries that have fully transitioned to IPV.

Conclusion: Ensuring Safety While Maintaining Immunization Levels

The rare case of vaccine-derived polio in Meghalaya has prompted health officials to remain vigilant. Even though such cases do not compromise India’s polio-free status, they highlight the need for careful monitoring and continued high levels of immunization. The challenge lies in balancing the effectiveness of the oral polio vaccine with the safety provided by the injectable vaccine to prevent future outbreaks.