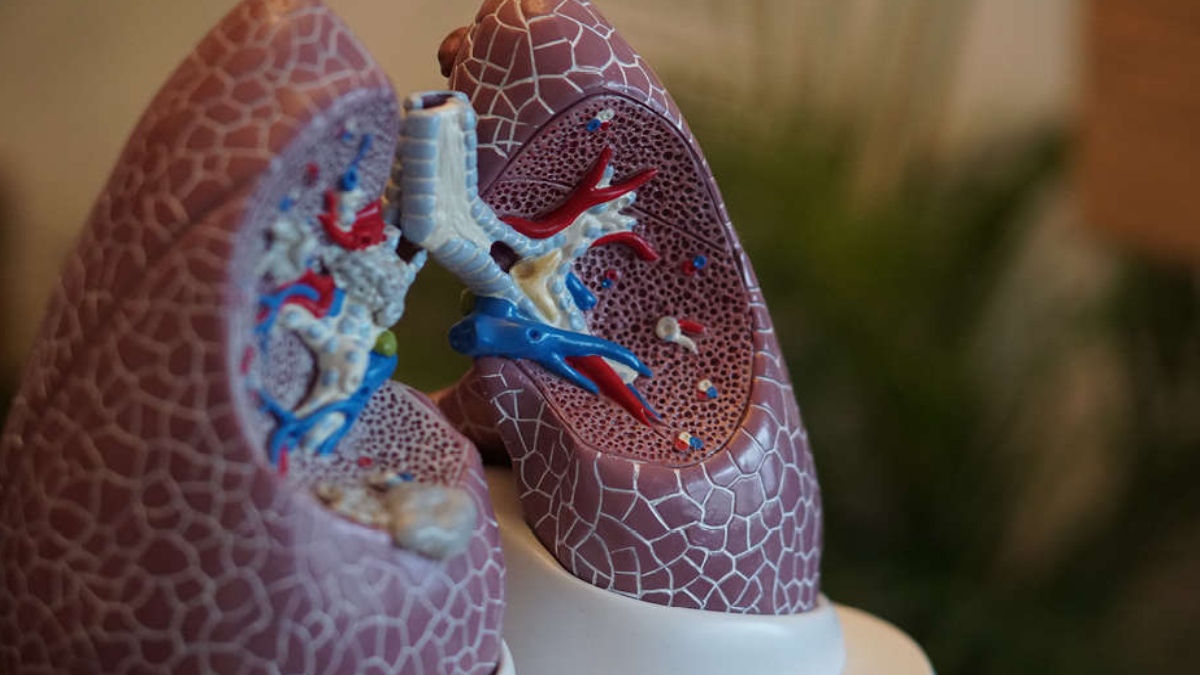

A recent study examined how persistent lung disease develops long after the virus has been cleared.

The findings of the study were published in the ‘Journal of Clinical Investigation’. The deadliest time in a viral respiratory illness sometimes is actually after the virus is cleared from the body.

Destructive processes that are set in motion during an infection crest in the weeks after the virus is defeated, leading to organ damage that can cause chronic illness or even death.

After an initial bout of COVID-19, for example, some people struggle with a persistent cough, difficulty breathing and shortness of breath — signs of ongoing lung disease.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found clues to just how lung damage develops in the aftermath of a respiratory infection.

Studying mice, they found that infection triggers the expression of a protein called IL-33, which is needed for stem cells in the lung to overgrow into air spaces and increases mucus production and inflammation in the lung.

The findings revealed potential points of intervention to prevent chronic lung damage caused by viral infections.

“Vaccines, antivirals, antibody therapies are all helpful, but they are not a solution for people who are already on the road to progressive disease,” said senior author Michael J. Holtzman, MD, the Selma and Herman Seldin Professor of Medicine and a professor of cell biology and physiology.

“We’ve gotten better at taking care of the acute illness due to COVID-19, but what happens after that initial injury phase is still a major obstacle to a better outcome,” continued Holtzman.

“At this point, we are also faced with tens of millions of people who already had an infection, and a high percentage of them are having long-term disease, especially with respiratory symptoms. We don’t have a treatment that can correct the problem,” added Holtzman.

It’s long been recognised that acute respiratory infections can lead to chronic lung disease.

Children hospitalised with the respiratory syncytial virus, for example, are two to four times more likely to develop asthma that persists for long periods, maybe even for a lifetime.

How exactly an acute respiratory infection triggers the chronic disease, however, is not fully understood, making it difficult to develop therapies to prevent or treat it.

As part of this study, Holtzman and colleagues, including first author Kangyun Wu, PhD, an instructor in medicine, studied mice infected with the Sendai virus.