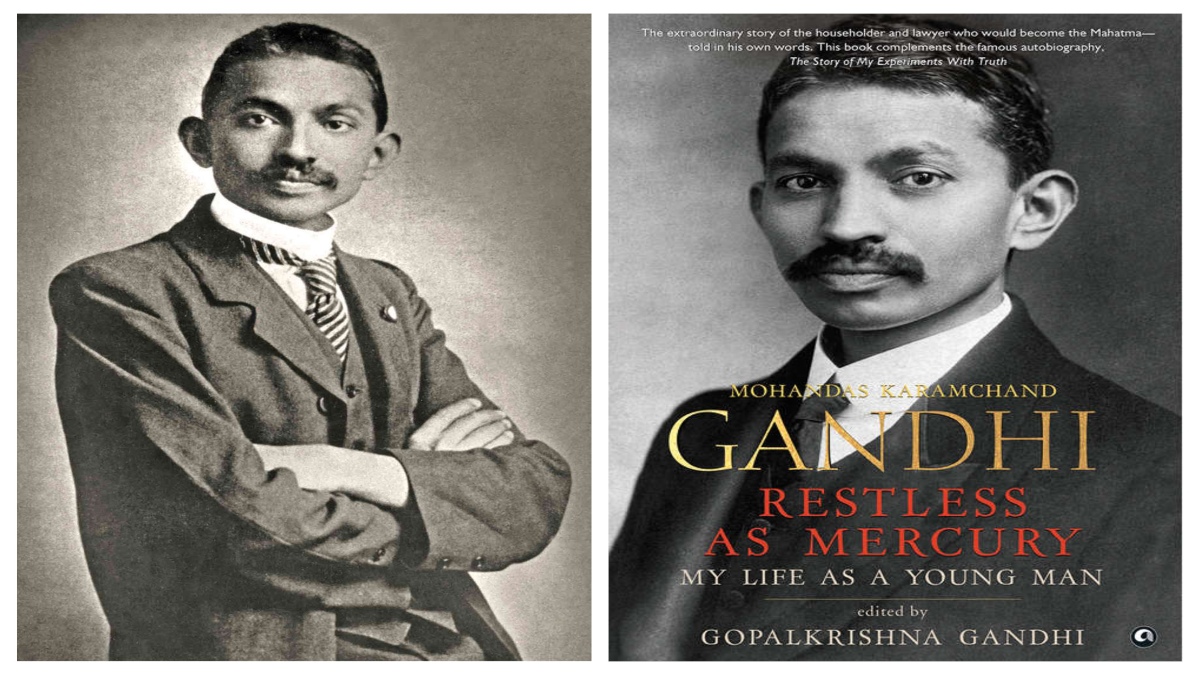

On 6 November 1888, that is, a little over five weeks after reaching London, I formally applied for admission to The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple as ‘Mohandass Karamchand Gandhi, aged 19, the youngest son of Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi, deceased, of Porbandar, India.’

Three days later I wrote to my brother informing him of my application and asking him why his weekly letters to me had slowed down. If I do not get letters every week, I feel very worried, I wrote, and urged him to please drop a postcard every week. I said the cold was now very bitter but I felt no need for meat or liquor, which fact filled my heart with joy and thankfulness.

A month later I penned the draft of a letter to Mr Lely telling him of my having joined the Inner Temple and asking him for a grant of 400 pounds as the 666 pounds that my brother had raised for me would not suffice for my needs. And I sent it to my brother asking him to hand it in person to the agent. I also wrote on similar lines to Colonel Watson, who had given me a letter of commendation. Telling him that I had comfortably settled and had fairly begun my studies, I said life in England was very expensive and asked him also for some substantial help to prosecute my studies.

Getting the right food had become an issue for me, a big issue. Vegetables cooked without spices or salt I could not abide. What could the landlady cook by way of my needs? The morning’s daily fare of oatmeal porridge did fill me up somewhat but by the afternoon and evening I would be famished. The friend would try every day to persuade me to give up my no-meat restriction. I would cite the vow and say nothing more. For lunch I would subsist on bread with marmalade and a green vegetable slop. The same or similar would comprise dinner. I could see that of the bread I was expected to take no more than two or three slices. To ask for any more would be unseemly and embarrassing. Now I was used to eating heartily. My appetite was robust and demanding. There was no milk to be had at lunch or dinner time. Seeing my predicament, he one day asked me: ‘When back home you had no need to eat meat you tell me you did eat it; now when you really need to do so, you are starving yourself. How strange!’

Dr Mehta and Bhai Dalpatram Shukla had me move shortly thereafter to new lodgings in the West Kensington home of an Anglo-Indian widow. She was apprised of my dietary quirks and was very understanding. But the hunger pangs stayed! The landlady had two daughters. They would urge me at table to ‘take a bit more of the bread’. Little did they know that what my growling stomach really wanted was the whole loaf. A wandering hunt for a vegetarian eating place started then in right earnest. My landlady said she knew such places did exist in London, but was not sure where they were. I would walk some ten to twelve miles looking for them, and fill my stomach with bread bought at some poor eating house. ‘Send me some mashala and fine-ground saalam,’ I wrote home, ‘in tin-plated lightweight containers.’9 One day my wandering feet reached Farrington Street and lo! there it was, a sign that said ‘Vegetarian Restaurant’. I was as a child that had found its heart’s desire. Buying a book called A Plea for Vegetarianism by Henry Salt for one shilling, I walked into the precincts to sit down for what was my first proper meal in England. God had saved me from hunger at last.

Honouring the word given to my mother was now not a matter of stern vow-keeping alone. It acquired the grace and fullness of joy.

What remained now was becoming an English gentleman.

I had brought ‘Western’ clothes with me but a Bombay cut is only a Bombay cut. That would not do in English society. And so I went to the Army and Navy Stores where a chimney hat to be sat on my head was bought for nineteen shillings. And then on to Bond Street, no less, where the elite had their clothes tailored. There, putting a hissing matchstick on full ten pounds, I got myself an evening suit. And as if this was not enough, I wrote to my brother to send to me a chain that would hold a pocket watch. My brother’s innocent and princely nature moved to do so at once and a heavy chain of pure gold arrived at this fop’s doorstep from home. It was long enough to work its way into not just the one pocket on the three-piece’s jacket, but two.

This was about appearances. What of culture? A cultured man about town must know to dance. He should be able to speak French, the lingua franca of all of Europe—which I wanted to tour. And he should be able to give a speech, fluently. So, I enrolled in a dance class. The first term cost three pounds. Over some three weeks, I took about six lessons. But the feet would not follow the beat. The piano would sing but I could not follow what it wanted me to follow. ‘One, two, three,’ it said, but at its own pace which was not mine. And so, what was I to do? A cat, says the proverb, must be got to catch the rat. I added to the accoutrements of culture. I started to learn to play the violin just so that I could get a sense of notes and beats. Three pounds went into the purchase of a violin and some more on its learning.

To learn the art of elocution, I went in search of my third teacher in gentlemanship. He cost me a guinea. I bought and started to read Bell’s Standard Elocutionist. It was when reading it that a ‘bell’ rang in my mind’s ears. Was I going to spend the rest of my life in England? How was my dance-learning going to help me back home? The violin I can learn to play when I return. I am here as a student. I should acquire but one asset: learning. I wrote to my elocution and dance teachers of my thinking. I took my violin to my violin teacher. She was most understanding. She said she would try to sell the violin for whatever value it fetched. She and I had got to know each other and so I told her of my realization that learning dance and music was a kind of delusion with me. She understood and appreciated what I said. The desire to be a gentleman had held me in its grip for some three months. The fascination with apparel lasted much longer. But I had at last become a student in London.