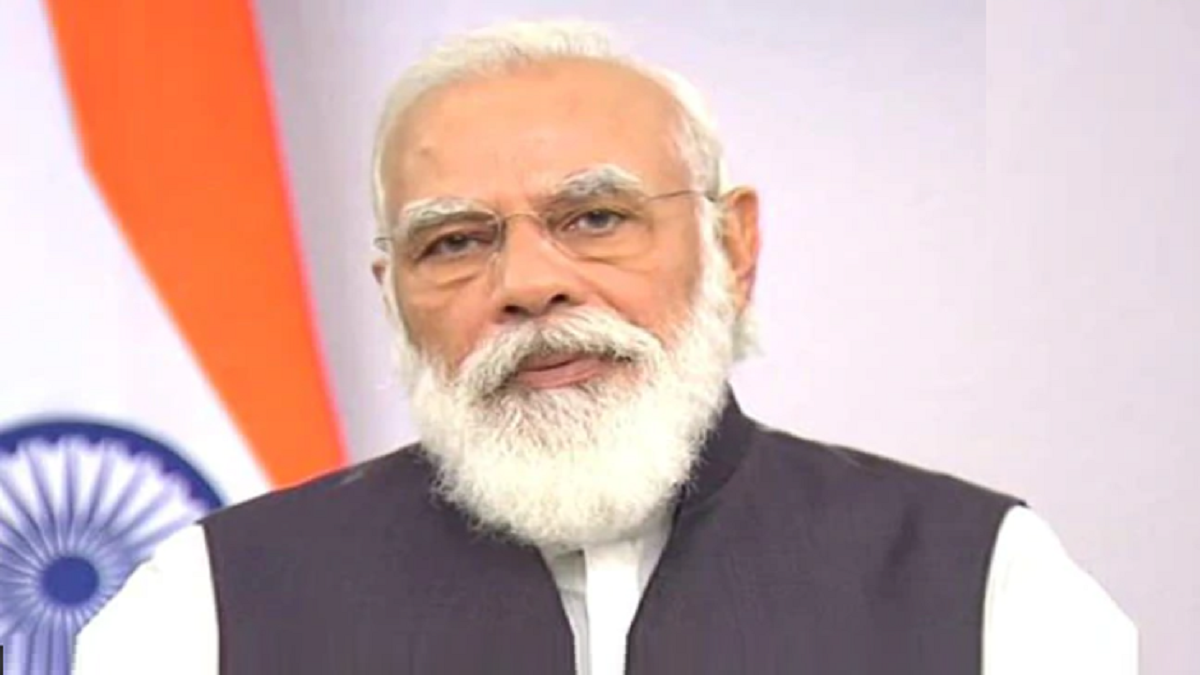

Three years ago, Lord Meghnad Desai, in a meeting with this writer, recalled an interesting incident of December 2007, soon after the Gujarat Assembly election results. Lord Meghnad was asked on live television to analyse then Chief Minister Narendra Modi’s electoral victory. Pat came the reply: “Modi is the next leader of the BJP.”

The statement provoked “surprise and some disgust”, as Desai recalled, among co-panelists, to the extent that noted social scientist Ashis Nandy gave a terse one-liner: “Over my dead body!” To this, Desai recalled saying: “Ashis, you and I are young enough and it will happen in our lifetime.”

And it did happen within seven years when Modi not just became the leader of the BJP but also the Prime Minister of the country and that too with a thumping majority — a first for any party in the last three decades of Indian politics.

But what Lord Meghnad said thereafter was an eyeopener and showcased the kind of scare-mongering that was being created around Modi. “First, they dismissed Modi and (Donald) Trump as outsiders who should not be taken seriously, and then, when the two got elected, this very liberal brigade mourned and screamed as if the entire world had fallen apart,” says Desai, recalling how a prominent member of Lutyens’ Delhi invited him to a qawwali event in May 2014 saying, “I must not miss the last qawwali programme in the city!”

Analysing the “liberal reaction” surrounding Modi, Lord Meghnad questioned the very illiberalism of the liberals. “They are liberals only when they win and are in a dominant position. It all changes when they are on the losing side,” he said matter-of-factly.

Nothing explains this better than the way PM Modi has traditionally been projected in the media. Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, in his biography Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times, too hints at this illiberal side of Indian liberals while talking about the Karan Thapar interview in October 2007 — two months before the Assembly elections that ended in a second consecutive victory for Modi. Recalling the much talkedabout Modi walkout from Thapar’s show, Mukhopadhyay accuses the anchor of “obviously playing to the gallery of Modi-baiters”, as “in all fairness, the question would have put off most political leaders”.

Interestingly, Modi’s foreign biographers could see the issue more succinctly. Lance Price, a British journalist, explains in his book, The Modi Effect, why Modi has reason to be wary of writers and journalists. “Few politicians in India have faced such a barrage of personal attacks as he has done since his first days as a public figure,” he writes. Similarly, British author Andy Marino’s account of the Godhra violence in his Modi biography avoids painting things in black and white.

This background is necessary to truly appreciate Arvind Chaturvedi’s new book, The Real Modi (published by Bloomsbury). For, it avoids the mistakes most biographers, especially Indian, have made while writing about Modi. For, Modi is not the sum total of Godhra. The problem is most analysts trying to analyse Modi have already a fixed notion about him: They first decide what Modi is or should look like, and then go about looking for evidence to bolster that claim!

Arvind Chaturedi avoids this pitfall. He, as the book’s title suggests, searches for the real Modi. He goes around looking for his roots in Vadnagar where Modi was born and brought up, meets his family members, relatives, neighbours, friends, teachers, et al, to analyse the phenomenon called Modi.

Reading the book, one realises that some of his works like Swachh Bharat, Jan Dhan Yojana or even the to ilet programme weren’t just fanciful projects for PM Modi (some “elitists” even abhorred the idea of a Prime Minister talking about these things from the rampart of the red Fort). These were the very things the Prime Minister had seen around while growing up in Vadnagar. He saw filth and lack of hygiene among people; he grew up seeing women facing toilet problems. He saw the poor facing issues in getting back accounts opened.

Writes Chaturvedi , “Their (Modi’s) single-storey house, tucked inside a narrow lane, was home to eight people. The house didn’t even have a bathing area and they had to make do with a makeshift bathroom with cloth curtains strung from three sides. Narendra Modi has experienced this painful existence from close quarters.”

One thing that comes across time and again in the book is Modi’s deep love and respect for his mother. Most of us still remember PM Modi – on the dais with Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg not very long ago — getting emotional while talking about his mother. People from different walks of life interpreted it differently, but while reading The Real Modi one realises the essence of that moment.

The author quotes Modi’s sister Basanti as saying how “Modi was the apple of his mother’s eye”. His younger brother, Pankaj, affirms this when he says, “Every day, their mother would save one bajra roti from lunch for Narendra Bhai. She would leave this roti on the pan till it became crisp like a biscuit. As a child, this was his everyday meal. He would dunk this crisp roti (made in the morning) in tea and enjoy it.” Modi’s another brother, Prahlad, adds to this saying that their mother never gave this roti to anyone else. One thing that often confuses traditional Indian intelligentsia, whether in media or academia, is PM Modi’s supreme confidence in pushing forward his programmes and initiatives once he makes up his mind. He never looks back. He never hesitates. He never appears to be in any kind of dilemma. Most of his critics see it as his arrogance. But when this reviewer once asked a Delhi-based senior journalist, who has been close to Modi when he was the Chief Minister of Gujarat, he just said one word: “Conscience”! When asked to elaborate, he stated, “Modi firmly believes that if your intentions are right, people are wise enough to understand and support you.” One may agree or disagree with some of PM Modi’s moves, from demonetisation to GST implementation, but the support he received from the masses, despite the hardships they faced, is a vindication of his faith. Chaturvedi too mentions this aspect of Modi while telling the story of one bank manager, Harshad Bhai.

The other part of the book that touches the chord of the reader is how PM Modi might have several SUVs at his disposal today, but what truly captured his imagination were his scooters. He had different scooters in different phases of his life. The author finds out more about Modi’s scooter rides and how the vehicle played an important role in his initial days in politics. Interestingly, Chaturvedi quotes his one-time colleague Shankersinh Vaghela as saying how Modi was very possessive about his scooter and never allowed anybody else to ride it.

This is a must-read book for anyone willing to find out the real Modi. It will help unravel some of the enigmas surrounding the PM, and also explain why he did what he did both as Gujarat CM and later as Prime Minister. As for those screaming “Chowkidar Chor Hai”, they should read the section where Modi was given a bag with Rs 50,000 during an RSS camp in 1969 with a request to return after it’s over in a few days. Modi dug a deep trench near the training camp late into the night and buried the bag there. For the next two days, he would sit there all day, till he was asked to return the money!

The book is an ultimate reminder of how wrong the liberals have been in understanding and analysing Modi. Maybe the Six years have gone by since Modi is in Raisina Hills. Qawwalis are still happening (maybe not now but blame Covid and not him for that) and will continue to happen. It’s time Indian liberals shed their illiberalism.

Excerpts from the book

Why Modi joined the Sangh

While researching for this book, I met Narendra Modi’s supporter, Dr Anil Rawal, who runs a clinic for the poor in Maninagar. Dr Rawal has worked for years with Modi. He shared a story to tell why Modi joined the RSS. Dr Rawal said that a swayamsevak’s job was to go around villages and towns, propagating the Sangh’s doctrine. In those days, they used to distribute vada and tea in the morning at the RSS office. In the evening, they used to visit some swayamsevak’s home for meals. This was their normal routine. In case they were unable to go to a swayamsevak’s house on any day, they had to go hungry. Once, Modi had gone to a swayamsevak’s humble home in a village. It was a family of three — a couple and their child. He had visited them during lunch time, and so, the couple invited him to join them for lunch. The wife had offered him a roti and some milk in a small bowl. But as Modi started eating he saw their child staring at the bowl. Modi felt that the milk was probably the child’s share, and so, declined to drink it. The mother picked up the milk bowl and gave it to her child who had gulped it down immediately. That incident had shaken him as he said that he had not seen a bigger sacrifice made by a mother, despite such poverty. Modi felt like honouring the couple for their sacrifice. He realised that even in this day and age, people have a sense of sacrifice and dedication. While leaving their home, he took a pledge to reach out to every unhappy and helpless person in the country. Dr Rawal revealed that it was this incident that convinced Modi to dedicate his life to the Sangh. After becoming the chief minister of Gujarat, Modi launched campaigns to provide food, clothing and shelter to the poor, and after becoming the Prime Minister, he promised the country that every poor would be fed, clothed and sheltered.

Modi and his love for cricket, kabaddi

There was another special quality in Narendra Modi: he rarely missed school. As a child, he always tried to reach school on time. He liked playing games. After becoming the prime minister, he asked the children on Teacher’s Day about how many of them really sweated it out at least four times a day. He told them that they should play a sport, have fun and play pranks. Narendra Modi was a good sportsman. He had no competition in swimming, kabaddi, kite flying, wrestling and cricket. He loved playing cricket. His classmate, Shyamaldas Madhav Das Modi, said he had put together a cricket team called Azad Team. Suresh Bhai, who was the captain, is no more today.

Scooter and the making of Modi

Today after becoming Prime Minister, Narendra Modi has several vehicles at his disposal, but the vehicle which played an important role in his initial days was his scooter. He had different scooters in different phases of his life.

Laxmanrao Inamdar’s only surviving brother, eighty-fiveyear-old Gajanan Inamdar, who retired from Ahmedabad Electrical Company, revealed that a bearded well-built young man used to drop his brother home on a cream-coloured scooter in the early 1970s. He also said the man taught his ten-year-old son how to ride a scooter. According to Premchand Kodar Bhai Patel, Narendra Bhai also had a Lambretta scooter in 1974. Though Premchand was unable to recall its number or colour, he said it was this scooter that Narendra mainly used for commuting.

Shankersinh Vaghela, who was then a leader in the Gujarat Vidhan Sabha, and now has his own party, said Modi was very possessive about his scooter and never allowed anybody else to ride it. He said he had covered huge distances with Modi on his scooter. Today, a grey scooter, numbered GJ-01-N-4242, stands parked at the Ahmedabad RSS office, telling us the story of how it had taken PM Narendra Modi closer to his goal. It is still in perfect condition. During his stay at the Maninagar RSS office, Modi used this scooter for commuting. According to Girish Bhai Patel, when Modi was given some responsibility in Karnavati Nagar in 1991, he made use of this scooter.

Its papers were issued in Narendra Modi’s name. After taking oath as the PM, Modi announced he did not want any valuables under his name and then the scooter was transferred to Yogesh Bhai. Girish Bhai who looks after the office vehicles in Ahmedabad, said that, normally, they replace the vehicles every four or five years. He also said that, presently, there are fifty-one pracharaks in the area and a total of fifty-two two-wheelers.

Shankar Singh Vaghela said that in the early days they had a Fiat car that they had bought for 22,000. I also met a veteran RSS worker, Harish Nayak, at the Ahmedabad Sangh office, who shared some interesting anecdotes about Modi’s scooter. He said that whenever Modi approached the scooter, he would first raise his left arm before starting the scooter. He did this to adjust his watch, which had been loose.

After his induction into the BJP, Modi became very busy. According to Gujarat organisational secretary, Bharat Bhai Pandya, after joining the BJP, Narendra Bhai used to commute by a cream-coloured Vespa scooter.