The celebrated Urdu writer Ismat Chughtai extensively wrote about freedom of speech, femininity, class conflict, homosexuality, and expression of female sexuality: The subjects continue to be as relevant today as they were when she first started out in the 1930s. The early phase of her writing career was marred by an obscenity trial where Chughtai had to defend herself in the Lahore Court in the year 1944—an incident which led to much controversy and uproar. The obscenity charges were leveled against Chughtai for a 1942 Urdu short story published in the Urdu literary journal “Adab-i-Latif”. Titled “Lihaaf” (aka “The Quilt”), the short story explores the theme of homoeroticism. Interestingly, Chughtai wasn’t put on trial alone. Another legendary Urdu writer was put on trial for obscenity alongside her. If you haven’t guessed it already, the writer was none other than Saadat Hasan Manto. Chughtai has given a detailed account of the trail in memoir “Kaghazi Hai Pairahan” (“A Life in Words: Memoir”).

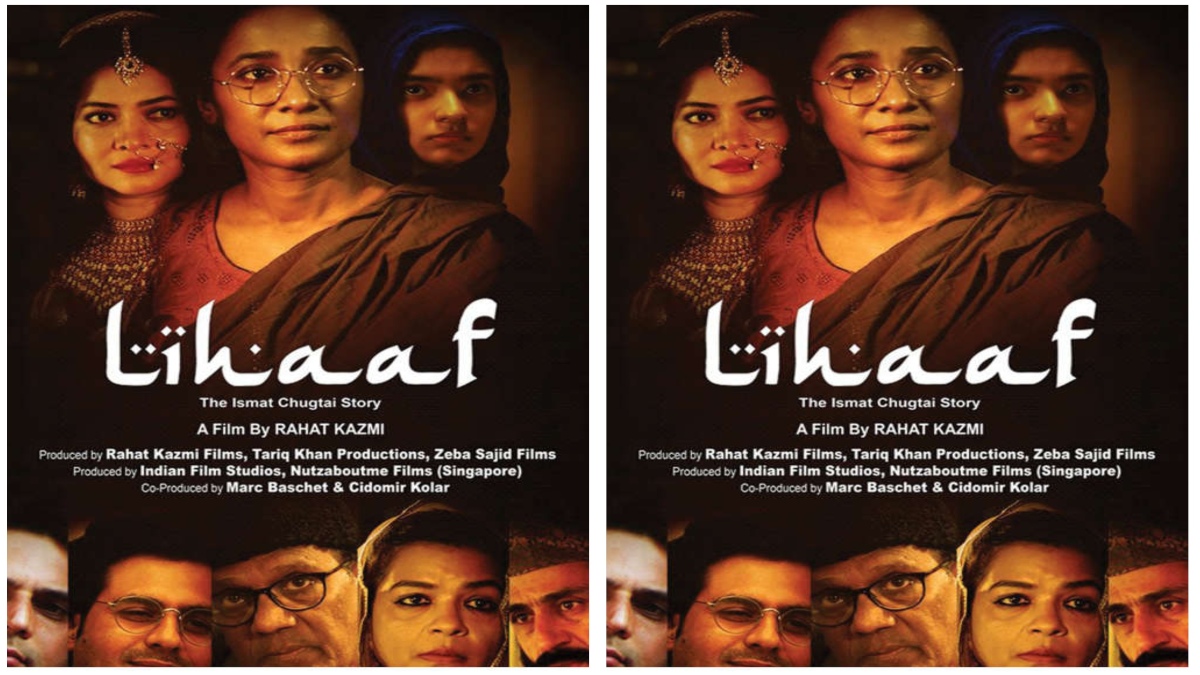

Rahat Kazmi’s period drama film “Lihaaf: The Quilt” which is being streamed by Voot Select as part of Voot Select Film Festival, a direct to OTT Film Festival, is not just a retelling of the story of “Lihaaf” as one would expect, but it also focuses on the aforementioned obscenity trial. The story begins when Chughtai, living in Mumbai, is summoned by the Lahore Court. Considering the charges of obscenity to be totally preposterous, Chughtai refuses to sign on the orders at first. She just cannot believe that the Lahore Court has actually put her on a trial for obscenity for a story like “Lihaaf” that makes no direct suggestion to any sexual act. Everything in the story is so subtle that it’s all up to the reader’s interpretation. That’s the exact argument that her lawyer makes in the court. Chughtai is essayed by Tannistha Chatterjee who never misses a note during her brilliant performance. The part of Manto is played with a refreshing playfulness by Shoib Shah who ensures that the controversial writer isn’t presented as totally humorless like was the case with Nawawuddin Siddiqui’s Manto (as good as the portrayal was) in the Nandita Das film.

The fact that Chughtai’s works continue to be as relevant today as they were several decades ago proves that our society hasn’t evolved much. Burdened by the weight of centuries old patriarchy, the women are still fighting the same fights, over and over again. Now, “Lihaaf” remains the most popular of all of Ismat Chughtai’s stories. While at the time it’s mostly received attention for its suggestion of lesbianism, it also deals with the solitary life of a neglected wife in the feudal society. Chughtai’s thought-provoking short story is considered to be a landmark not just in Urdu literature but also in modern Indian literature which continues to see sex and homosexuality as a taboo.

The story of “Lihaaf” is told through the point of view of a small girl who is temporarily left by her mother to live with Begum Jan. The screenplay of Rahat Rahat’s film, co-written by Sonal Sehgal and Rahat himself, assumes the young girl to be none other than Ismat Chughtai herself. Begum’s depressing life after marriage to a Nawab in the 1920s Agra is intercut with Chughtai’s obscenity trail in the Lahore Court. Begum’s husband is much older than her. He is highly respected by those around her for never having any affairs with prostitutes—a trait that most Nawabs are notorious for. But it is soon revealed that it is because of his attraction to younger men. Meanwhile, the lonely Begum gets ill but is saved by Rabbo, her masseuse, who is very skilled with her hands. When the young Ismat Chughtai is left at Begum Jan’s place by her mother, she begins to make some interesting observations about Begum Jan and Rabbo. At night, she gets petrified by the great shadows formed by the exaggerated movements of Begum Jan’s quilt. Also, she is perplexed by Begum Jan’s mood swings and odd behavior when Rabbo goes away to stay with her family for a few days.

The film’s co-writer Sonal Sehgal, who previously worked with Rahat Kazmi on ‘Mantostaan’, also essays the complex part of Begum Jaan. As part of her preparation, Sehgal cut herself off from the world as she wanted to feel the Begum’s pain and loneliness. Begum Jaan is a victim of her circumstances as well as a perpetrator of crime against the helpless young girl. During the shoot, Sehgal requested the entire cast and crew to leave her alone as she restricted herself to her hotel room at all times except during her takes. And it shows on the screen. Mir Sarwar is also superb in the role of the Nawab. To his credit, Kazmi succeeds in bringing the story of the same sex relationship between a noblewoman and her masseuse back to life in all its glory almost eight decades after it was first published. Here is a film that needs to be watched.