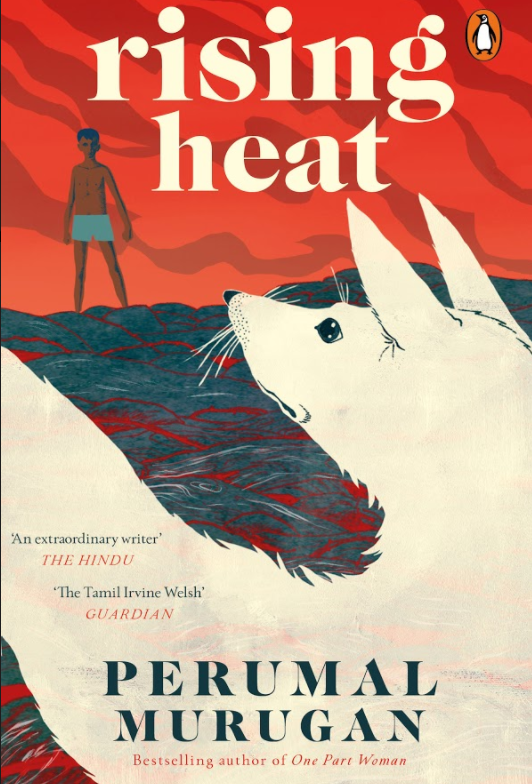

Rising Heat

Perumal Murugan

Penguin, Rs 399

A few years ago, Tamil novelist Perumal Murugan put a post on his Facebook wall, which read like a suicide note. “Author Perumal Murugan is dead. He is no God. Hence, he will not resurrect. Hereafter, only P. Murugan, a teacher, will live,” it said. The Murugan episode was an uncanny reminder of a similar event which took place on a sunny October day in London in the late 1980s, when Salman Rushdie was asked by a BBC reporter how he felt post the Ayatollah Khomeini fatwa. “I’m a dead man,” Rushdie wrote in his 2012 memoir, Joseph Anton, recalling that fateful day.

The two incidents may have happened over two decades apart but a common link exists. American writer Daniel Pipes believes TheSatanic Verses ban changed the very rule of the game. Thereafter came into existence “the Rushdie rules” whereby, as Pipes explains, “editors, authors, publishers and academic teachers abide by a new set of rules which limit the freedom to discuss Islam with the same methods, terminology and frank inquisitiveness which are considered normal in discussing Christianity and Hinduism”. If the Rushdie book ban made Indian Muslims look like “a bunch of humourless touch-me-nots, intolerant of elegant verses or an irreverent idea”, as Saeed Naqvi would say soon after the incident, it also emboldened fringe elements among Hindus to ape their Islamist rivals.

Years later, Murugan concedes he hasn’t yet come out of the shock of the raucous protests he met following the publication of his novel, One Part Woman. “The fear and the anxiety that the controversy has brought is still in the back of my mind and I constantly think about that. I feel the fear and anxiety will never go away,” he says, adding that he is now a more “cautious” and “measured” writer.

One tends to believe the novelist who, when asked what is keeping him busy during these Covid-ridden days, says that he has bought two buffaloes and is busy looking after them — and in between, he has written about 20 short stories and a few poems. The following are excerpts of the interview with Murugan:

Q. Your latest book, ‘Rising Heat’, happens to be your first book too, which came out in Tamil way back in 1991. Please tell us about your trials and tribulations when the book was being published in 1991.

A. It was quite a struggle to get this book printed. At the time when this book was being published in 1991 in Tamil, the Tamil publishing world wasn’t the same as it is today. They were only interested in publishing works of famous writers at that time like Sujatha and Balakumar. They were not interested in published serious subjects, and even if they did publish they were limiting themselves to established writers. So the new writers had to put their own money to get their work published. I also had to put my own money to get the first book published. But since I didn’t have the required money, one of my closest friends put in his money to get the first book published.

Q. The plot of this novel revolves around the changes faced by an agrarian family in Tamil Nadu after the state acquires its farmland to build a housing colony, and is said to be drawn from your own life. Please tell us more about the book, and how much of it is autobiographical.

A. The base of the novel is entirely autobiographical. My family and relatives were displaced by the government when they took over 100 acres of their land and they were removed from their own ancestral properties. So that was the basis of the story and there was no doubt about that. Some fictional elements were introduced, but how much of it is fiction and how much is reality is something even I can’t exactly tell you. All I can tell is that almost 50 per cent of the story is autobiographical.

Q. Caste often makes an appearance in your novels. What makes caste such an important background in your books?

A. If you write about villages, you just can’t write without talking about “jaat” (caste). Even today, in villages, people still live and abide by rules of the caste system; different castes live differently, and owning land remains the privilege of the few and the rest have to comply and live with these rules. So, if you have to write about villages, you just cannot not write about caste.

Q. The book also talks about protests against the imposition of the Hindi language. It’s a sensitive subject, and one which often comes up in our national discourse. What is your take on it?

A. First of all, it’s not a protest against Hindi. It’s actually a protest against forcing the study or learning of Hindi. And to force anyone to learn anything other than their mother tongue is something that anybody who works in languages would oppose. The mother tongue needs to be studied, everything else is an option. It should be the choice of the person if he or she wants to learn a language outside their mother tongue. It can’t be insisted upon or made a part of the curriculum. In other states, they have a three-language policy. In Tamil Nadu, we have a two-language policy: Tamil as first language and English as the second. Anything beyond that should not be insisted upon.

Q. You faced a lot of hardships after the publication of your book, ‘One Part Woman’. How do you look at that entire episode now, almost a decade later? And how has it impacted you as a writer and an individual?

A. When I wrote that book, I didn’t expect that it would get so much attention. Even when I wrote Rising Heat, I didn’t think it would even be accepted as a novel. So when I wrote One Part Women, I wrote with the same sort of ease of writing and didn’t think that it would get the notice it ultimately did. But now it holds the most significant place among all the books I have written. Looking back, I sometimes wonder if I could have written all the elements that made the novel so controversial. The fear and the anxiety that the controversy has brought is still in the back of my mind and I constantly think about that. I feel the fear and anxiety will never go away.

Q. So you are saying you have matured as an individual and a writer post that incident?

A. Absolutely, no doubt about it. Nowadays, I am very cautious to not mention any caste or names of places and also make some generic atmospherics. After writing, I go back again to edit consciously what I have written.

Q. You mentioned an ease of writing. Is that ease of writing still there, or is there no pressure to perform?

A. I am a college principal and also do farming. I write when I have an urge to write. In these Covid times as well, when people are writing novels, I have written some short stories and poems. I keep my creative juices alive by doing things but I need to first have the urge.

Q. What’s keeping you busy these days amid Covid-19?

A. In the first two months of Covid-19, I couldn’t go out and was forced to stay at home. At that time, I wrote about 20 short stories. In about mid-May, the college work resumed. I also have a farm, and recently bought two buffaloes. I am taking care of them, and in between all this, I have written a few poems as well.