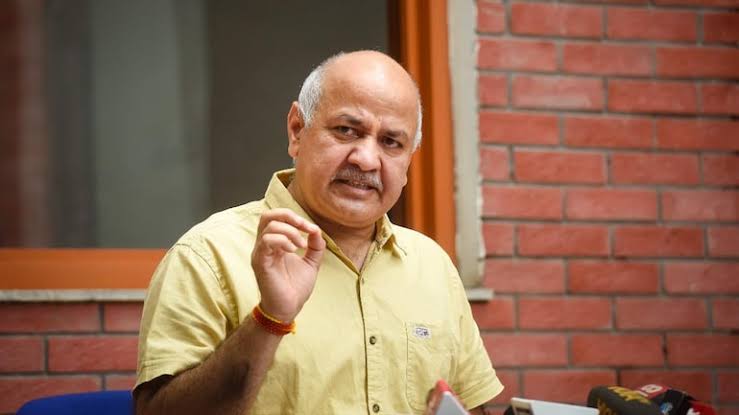

The controversy around the Delhi government’s liquor policy, followed by the Central Bureau of Investigation raids at Delhi’s Education Minister’s (and Deputy CM) office and residence has generated a renewed enthusiasm around the Kejriwal model. On 20 August, Manish Sisodia, the Minister in question, declared in a press meet, that 2024 General Elections will be Aam Aadmi Party versus Bharatiya Janata Party. Sisodia used a New York Times report praising the AAP’s school education model in Delhi, contrasting it with the report on Yogi’s pandemic management in the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. This NYT report stated UP government’s “colossal failure to strengthen rural health care or ensure adequate vaccine supplies—or take responsibility for its shortcomings”. Why is it necessary for Sisodia to pit these two reports against each other? The central aspect of political communication is the intent toward a successful appeal. The speaker hopes to persuade the audience to favour him against his opponent. As Sisodia attempts to invoke national pride, “kal jab yeh khabar chhapi, ek Bharatiya k naate aapko garv hua” (Once this report got published, you must have felt proud as an Indian), he hurts the same pride turning it to national humiliation by referring to UP’s Covid mismanagement. The appeal is rendered unsuccessful as the audience takes home a null element, the pride being numbed out by humiliation.

A successful rhetorical appeal will speak to all the three, logos (logic); pathos (emotion); and ethos (personality eulogy of the speaker that the audience can identify with), of the audience. All at once. While both cases can be true: UP government did not manage their Covid crisis well and schools in Delhi did get better in the AAP years, it’s mention in a speech where Arvind Kejriwal is to be declared a better PM candidate than Narendra Modi, fails to send an adequately strong message. At best, it shows Yogi is not as good a CM as Kejriwal is. The question that Sisodia attempts to settle by referring to the two reports is neutralized by the contestation he creates between pride and humiliation. The rhetorical argument becomes vulnerable with such inner contradictions. It becomes easy for a more potent populist politics, such as BJP’s, to dismiss the very premise of the Opposition’s argument. We can see Sanjay Singh, AAP MP, battling such dismissal by defending the NYT now—the campaign pitch towards 2024 lost in conversation. For a party like the BJP, which enjoys tremendous mass support, it is not difficult to establish NYT as an anti-India; anti-national newspaper.

The Opposition will have to generate hope and utopia in the public psyche, and an unwavering trust that the alternative suggested is simply better for the whole country. Any leader who chooses to challenge the NaMo dynamics will have to accept that we are far past a situation where negative campaigns can be the primary assault. BJP, under Vajpayee’s leadership, employed rhetoric towards negative campaigns against the INC till 1986-87. However, its limited success in both the regional and national electoral politics was only corrected after Advani took lead and solidified the utopic alternative of Hindutva politics with the Ram Janmabhoomi Andolan.

Indian politics has always favoured leadership that could generate an aspirational zenith on its own accord, where negative campaigns have merely aided the conversation. This is precisely why NaMo’s Gujarat model; personal charisma in being Purushottam; successful journey from being an OBC chaiwallah to a CM—were all central to the 2014 campaign, though there was already a weakened Congress under attack from the India Against Corruption/ Anna Hazare Movement. NaMo’s candidature stood alone in its grandeur, with corruption charges against the INC only regenerating the need to side with such grandeur.

Over the last one month, we have seen raids in Kolkata with Trinamool ministers having to do away with their hidden cash stash, a new CM in Maharashtra risen from a BJP-guided coup, and Nitish Kumar in Bihar breaking away from the NDA government to lead the JDU-RJD government as CM.

A reading in rhetorical political communication will find Kejriwal and NaMo competing with each other. Their style of communication remains the same. But the content of their rhetoric differs widely. While Kejriwal’s rhetoric is more oriented toward crafting his representational and governance strengths, thereby drawing legitimacy for his personality by mobilising the ethos or the logos of the audience, NaMo’s rhetoric attempts to operate at all three levels of persuasion: ethos; pathos; logos. The BJP’s invocation of emotion into politics through mobilising Hindutva and nationalism situates it way ahead of AAP.

Public opinion specialists often discourage such logical arguments when in mass politics because of several factors: one being that it is a rather irrelevant memory and people cannot immediately connect with this 2021 incident; and another very potent factor being that this cannot be turned into a shared sensibility of the mass as the percentage of voters bothered with fake news or with NYT is significantly small, and largely urban.

Opposition leadership, countrywide, will have to battle the inability to tap into the majority’s shared knowledge, alongside actually communicating a singular face of the Opposition—if at all. Nitish Kumar, Mamata Banerjee, Kejriwal or Pinnarayi Vijayan, none has the upper hand in discourses and arguments which polarise the socio-political and become identical to the shared knowledge of the audience, or voters, which scholars will refer to as the Aristotelian enthymeme. In an electoral democracy where numbers matter to the end that ministers hire campaign management firms at the drop of a hat, the Opposition must have a winning impact upon public opinion. Singh proclaimed that Kejriwal is the answer to the question, ‘Modi nahi toh kaun?’(If not Modi, who?). AAP will only have a successful sway at the 2024 battle if it can turn around the question on its head, and ask, ‘Kejriwal nahi toh kaun?’(If not Kejriwal, who?), and this will require a complete overhaul of its engagement and outreach strategy, right from the constituency level.

Ankit Singh is the recipient of the Developing Nations Scholarship, MPSA 2022. He currently works as a geopolitical analyst, and researches rhetorical performance in political communication as a Scholar at Centre for Political Studies, JNU, New Delhi.