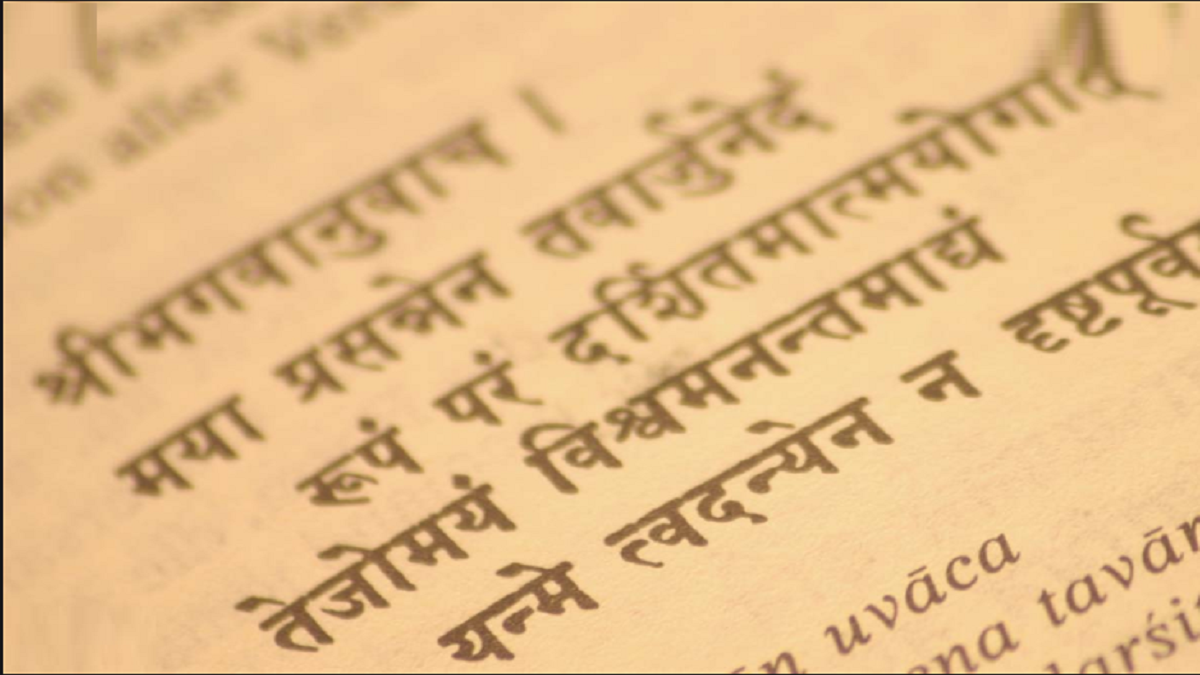

The Sanskrit Week (2-8 August) is being celebrated, though mostly online, this year. Circa 1290 AD (Saka 1212), a teenaged mystic from Maharashtra accomplished a path-breaking work. Jnanadeva (1275-1296 AD) composed Jnaneswari, an exposition of the Bhagavad Gita, in 9,000 stanzas of exquisite poetry in Marathi. He also composed Amritanubhav and Abhangs to Lord Vitthal in Marathi. He thereby brought about a revolution in the matter of languages. Jnanadeva stood on the same Advaitic (non-dualist) ground as Adi Shankaracharya, but despite being well-versed in Sanskrit, used a vernacular language to convey his sublime philosophy.

This was a new trend that would become the hallmark of second millennium. In that millennium, knowledge of Sanskrit would still be held in high esteem across India. A small group of ‘Pundits’ working mostly on Nyaya philosophy, Smriti (Hindu law), grammar, literature would cultivate it diligently. It would even captivate the imagination of foreign scholars for its ancient gems. But the language, as the millennium progressed, would gradually cease to be a medium of new and original creations. More strikingly people well-versed in Sanskrit like Sankardev of Assam, Goswami Tulsidas, Bhadrachala Ramdas and Sant Tyagraj of Andhra Pradesh, poet Bharat Chandra of Bengal, Swami Dayanand Saraswati would themselves switch over to a modern Indian language to create a mass discourse based on Indian ideas.

The second millennium in India was marked by Muslim invasions out of Central Asia. These invasions had a cataclysmic effect on the political, social and religious fabric of India. Temples, monasteries, universities and playhouses, at least in northern India, were laid to waste. Not only was the client-patron relationship that had sustained Sanskrit was destroyed, but also the innocence of the civilisation that upheld transcendental thoughts was gone. The new Turk rulers brought in Persian, which became the standard language of governance in India under the Mughals. Thus Sanskrit, or for that matter any Indian language, was deprived of state recognition and patronage. However, even under such adverse conditions, the modern Indian languages experienced efflorescence. This was due to cultivation of the local languages, by the saint poets. Goswami Tulsidas, himself well-grounded in Sanskrit, chose to write his Ram Charitmanas in Awadhi dialect. Though Tulsidas came under fire from the “Pundits” of Varanasi, he received strong support from Acharya Madhusudan Saraswati, a senior Bengali Advaitist who was a resident of the holy city. Madhusudan Saraswati, a stalwart of Advaita philosophy, and author of Advaita Siddhi, was possibly the last great Indian to have made his mark by writing solely in Sanskrit.

However, there is the example of Chandrashekar Samanta alias Pathani Samanta (1835-1904), who chose to write his astronomical treatise Siddhanta Darpana (1899) in Sanskrit language but Odia script in the late 19th century. Whereas Samanta’s observations “with home-made instrument and without optical assistance” with astonishing accuracy drew him plaudits from a British astronomer like E. Walter Maunder, still his treatise unlike those written by his contemporary Bal Gangadhar Tilak failed to enter the discourse. Tilak, proficient in Sanskrit, and Marathi, deliberately chose to write his two treatises The Orion and The Arctic Home in the Vedas in English. Samanta’s choice of language is illustrative of the isolation of his work in the 19th century milieu. In the times of Aryabhatta I, Varahmihira, Brahmagupta and Bhaskara II, Sanskrit was the medium of astronomical work in India. However, in Samanta’s time, those who knew astronomy no longer knew Sanskrit, and those who knew Sanskrit did not know astronomy. Samanta’s work had ceased to have any practical value in astronomy when Arun Kumar Upadhyay, IPS, translated it into English exactly a century later.

This has actually been the tragedy of Sanskrit. It ceased to be a medium of knowledge production for which it was once renowned. In the first millennium all kinds of scholarship in India was pursued in Sanskrit — from astronomy to yoga, dramatics to zoology, aesthetics to political science, architecture to military knowledge. A language can only grow when there is an ecosystem of knowledge around it. The same has ceased to exist for Sanskrit long ago.

Sanskrit had to readjust its social role since the beginning of the second millennium when the regional languages began to grow. The output in those languages, however, was confined mostly to poetry and devotional texts. Knowledge production itself received a setback in India due to adverse political circumstances. Even printing press had not been set up on regular basis in India until the late 18th century. The 19th century was an interesting time when English language burst upon India. There are a couple of things which need to be noted about the implication on English visà-vis Sanskrit.

First, there was nothing in the British policy that discouraged Sanskrit. As part of Orientalism espoused by Warren Hastings the British promoted classical languages like Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian. The British actually founded Govt Sanskrit College in Varanasi in 1791 (now Sampurnananda Sanskrit Vishwavidyalaya), Hindoo College (now Deccan College) in Pune in 1821 and Sanskrit College in Kolkata in 1823. Rather it were the Indians themselves who wanted to study English for the modern, practical, global and updated knowledge available in that language. Therefore, we see Indians establishing Hindu College (now Presidency University) in Kolkata in 1817, Elphinstone College in Mumbai in 1834, and demanding the conversion of Hindoo College Pune teaching Sanskrit into Deccan College teaching English. Even when the East India Company withdrew from teaching of classical languages, in pursuance of Macaulay’s minutes on education, Sanskrit departments continued in colleges and universities maintained at government’s expense.

Second, Sanskrit unlike other modern Indian languages failed to take advantage of its commerce with the English language. Sanskrit did get the advantage of standardisation of texts, and advantage of printing technology. However, it could not produce anything new even in the field of literature, let alone comprehensive knowledge production for which it was once known. Why Sanskrit failed to produce a Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Munsi Premchand, Subramania Bharati or N.C. Kelkar — all of whom brought honours to their mother tongues under the same British rule? Sanskrit since then has failed to develop modern literature, journalism, music industry, and film industry. It has become a curriculumcentric language.

Today, the best thing Sanskrit scholars hope for is better patronisation of Sanskrit by the government. This would lead to opening of more educational institutions for Sanskrit, thereby creating more jobs for Sanskrit scholars. Sanskrit scholars today are often scarred lot because job opportunities in the field are extremely limited.

The new National Education Policy, 2020 envisages linking Sanskrit to different disciplines. This could mean a person studying for MBBS should know something of Ayurveda, a person pursuing B.Arch should know basics of Shilp Shastra, someone studying theatre should know about Bharat Natyashastra, or a student of B.Tech (Metallurgy) know something about ancient Indian achievements in that field. In the modern times we have seen Sanskrit itself becoming a temple and museum, rather than a language and laboratory. This has harmed the cause of Sanskrit, rather than helping it. It is time we had a fresh look on Sanskrit.

The writer is an author and independent researcher based in New Delhi. The views expressed herein are his personal.