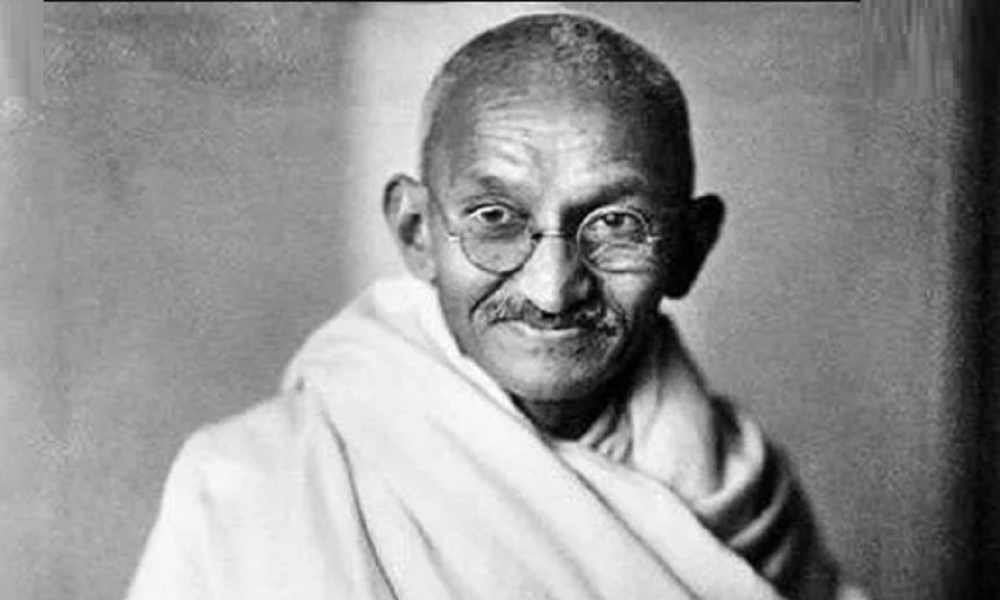

On this Gandhi Jayanti on 2 October, also known as the International Day of Non-Violence following a 2007 resolution passed by the UN General Assembly, let’s pause to remember the Mahatma in a less serious, almost light-hearted fashion.

Anyone familiar with Gandhi’s life and writings would know that he possessed a great sense of humour, and he also did not mind it overmuch when others made fun of him. On a certain occasion, Sardar Patel called him a true ‘bania’ when despite being unwell, he got up from his sick bed in order to meet with industrialists who came to attend an event with the idea of making a possible financial contribution to the coffers of the Indian National Congress. Gandhi, the Sardar joked, had been roused because the ‘bania’ in him at once caught the scent of money.

The Mahatma had a witty side to his personality and once remarked that he would have committed suicide long ago if he did not have a sense of humour. In 1931, he met King George V, grandfather of the recently deceased Queen Elisabeth at Buckingham Palace. Gandhi was dressed in his usual simple and modest attire, and after his meeting he was asked by a correspondent if the king had anything to say about his attire. ‘What could he say?’ joked the Mahatma. ‘He was wearing enough for the two of us.’

Sometimes though, Gandhi was also unintentionally humorous. The image of goat’s milk being brought in for him from the palace kitchen while King George V sipped tea in his study, still makes us smile. It would considerably humanise the Mahatma and make him more relatable to the younger generation, were more to be written about these aspects of his personality. Experts on Gandhi, and others who claim to have been influenced by him, should consider writing a book on him specially targeted at children and young adults.

An example of unintentional humour can be found within the pages of Hind Swaraj. Gandhi is determining how to respond to an imaginary situation where a robber has entered his home and he pauses to consider the possibility that the thief was his father.

‘I fancy,’ he writes, ‘that I should pretend to be sleeping whether the thief was my father or that strong armed man.’

At this point, a reader might imagine that Gandhi would pretend to be sleeping in the case of his father owing to traditional Indian reverence for the elderly. After all, how distressing would it be to find one’s own father a thief, and that too in one’s own house! This is not at all what the Mahatma means to say, however.

‘The reason for this,’ he writes, with unintentional humour, ‘is that my father would also be armed.’

Gandhi does not explain anywhere why he is so certain that his father ‘would also be armed’ but the observation raises a chuckle in the mind of the reader.

The humour exists partly because Gandhi has reversed the unexceptional scenario where a son tries to rob or steal from his father. In today’s times it would surprise no one, if a son stole money from his father, especially if he was young and short of money. In a lighter vein, and without in any way endorsing theft, in families and nations where there has been advancement in women’s rights, daughters too may steal from their fathers and even mothers – although such progress in gender equity may be considered highly dubious.

A second reason why the example given by the Mahatma’s tickles the funny bone is because of the image it conjures up. Eventually, Gandhi came to live in such simplicity that even a robber would have felt ashamed and turned away. This is, after all, the man, who was eco-friendly much before it became fashionable, who used a pencil till the very end, rather than throw it away when it became less comfortable to grip. Rather than buy a new pair of frames for a pair of damaged spectacles, the Mahatma would carefully consider, much before the concept became a management buzzword, if any ‘jugaad’ was possible by tying some string. A hypothetical robber may have departed Gandhi’s home with a feeling of pity, and even considered leaving a brand-new pencil to replace the pencil stub the Mahatma made do with.

Unintentional humour apart, Gandhi’s discussion of non-violence in Hind Swaraj is simple, yet brilliant. What stands out in his analysis is that there is no one size fits all solution he advocates while using nonviolence. He would handle a robber differently if he were unarmed and differently if he were armed. He would also handle a robber differently if he and the intruder were somehow related, such as when the intruder happened to be his father.

If you stop to think of it, given our shared cultural heritage with Pakistan, in the violence that followed the terrible Partition of 1947, which broke the Mahatma’s heart, brother was pitted against brother, father against son, and vice versa, so perhaps Gandhi’s example should be taken in that context. Warfare between groups who share ethnicity, culture, language and religion often takes place whenever nations break up anywhere in the world, and also when neighbours go to war.

Closer to present times, millions of ethnic Russians who are citizens of Ukraine, are embroiled in the present conflict with the Russians. There too brother is pitted against brother, and father against son, and there does not appear, thus far, to be any end in sight. Leaving aside the issue of cultural, ethnic and other affinities, are all humans not brothers and sisters in a sense? Even if we discount the biblical Adam and Eve story, many scientists believe we all descended from a common African ancestor.

To come now to the reason why Gandhi travelled third class. Ostensibly, it was to express solidarity with the poor and downtrodden. His own response, though, to a reporter’s question on the issue was: ‘Because there is no fourth class.’

(Rajesh Talwar is an author of 34 books across multiple genres. He has worked for the United Nations for over two decades across three continents in numerous countries.)