Water has always been central to civilisation across societies, including India, shaping settlement patterns, agriculture, economic development, and public health from early riverine cultures to the present day. In the twenty-first century, however, water governance has acquired strategic significance, emerging as a core pillar of climate resilience, food security, social stability, and inclusive growth. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Viksit Bharat 2047 vision, India has moved decisively beyond fragmented, infrastructure-driven approaches towards an integrated framework of water governance that seeks to balance access, sustainability, and ecological health. At the heart of this transition stands the Ministry of Jal Shakti, led by Union Minister C.R. Patil.

Since assuming office in mid-2024, Patil has articulated a governance framework anchored in three priorities: ensuring universal and reliable access to drinking water, particularly in rural India; advancing groundwater conservation and recharge in water-stressed regions; and strengthening scientific river and ecosystem management that integrates environmental protection with livelihoods. This shift, from scheme-centric execution to system-wide governance, marks an important conceptual advance. Yet, given the scale and diversity of India’s water challenges, this transition remains a work in progress rather than a finished outcome.

The institutional consolidation achieved through the creation of the Ministry of Jal Shakti in 2019 has undoubtedly strengthened coordination across drinking water, sanitation, groundwater, and river rejuvenation. The Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) stands out as a major achievement, expanding rural tap water coverage from 3.23 crore households (17 per cent) in 2019 to over 15.44 crore households (79.74 per cent) by February 2025, with several states achieving full coverage. Equally significant is the emphasis on decentralised governance through Village Water and Sanitation Committees, women-led water quality monitoring, and time savings that translate into improved livelihoods.

However, as coverage approaches saturation, the central challenge shifts from connections to continuity. Ensuring regular supply, water quality compliance, financial sustainability of village-level systems, and technical capacity at the Panchayat level will determine whether Har Ghar Jalremains a durable public service or risks uneven performance across regions. Greater attention to operation and maintenance financing, capacity building of local institutions, and real-time monitoring will be critical in the next phase.

On groundwater, programmes such as Jal Shakti Abhiyan – Catch the Rain, Atal Bhujal Yojana, and Jal Sanchay Jan Bhagidari (JSJB) 2.0 signal a welcome shift towards community-led and science-backed conservation. The reported increase in groundwater recharge and reduction in extraction reflects early gains. Yet groundwater stress remains structurally linked to cropping patterns, electricity pricing, and irrigation practices. Without deeper integration of water policy with agricultural incentives, crop diversification, and demand-side management, recharge efforts alone may struggle to keep pace with extraction pressures.

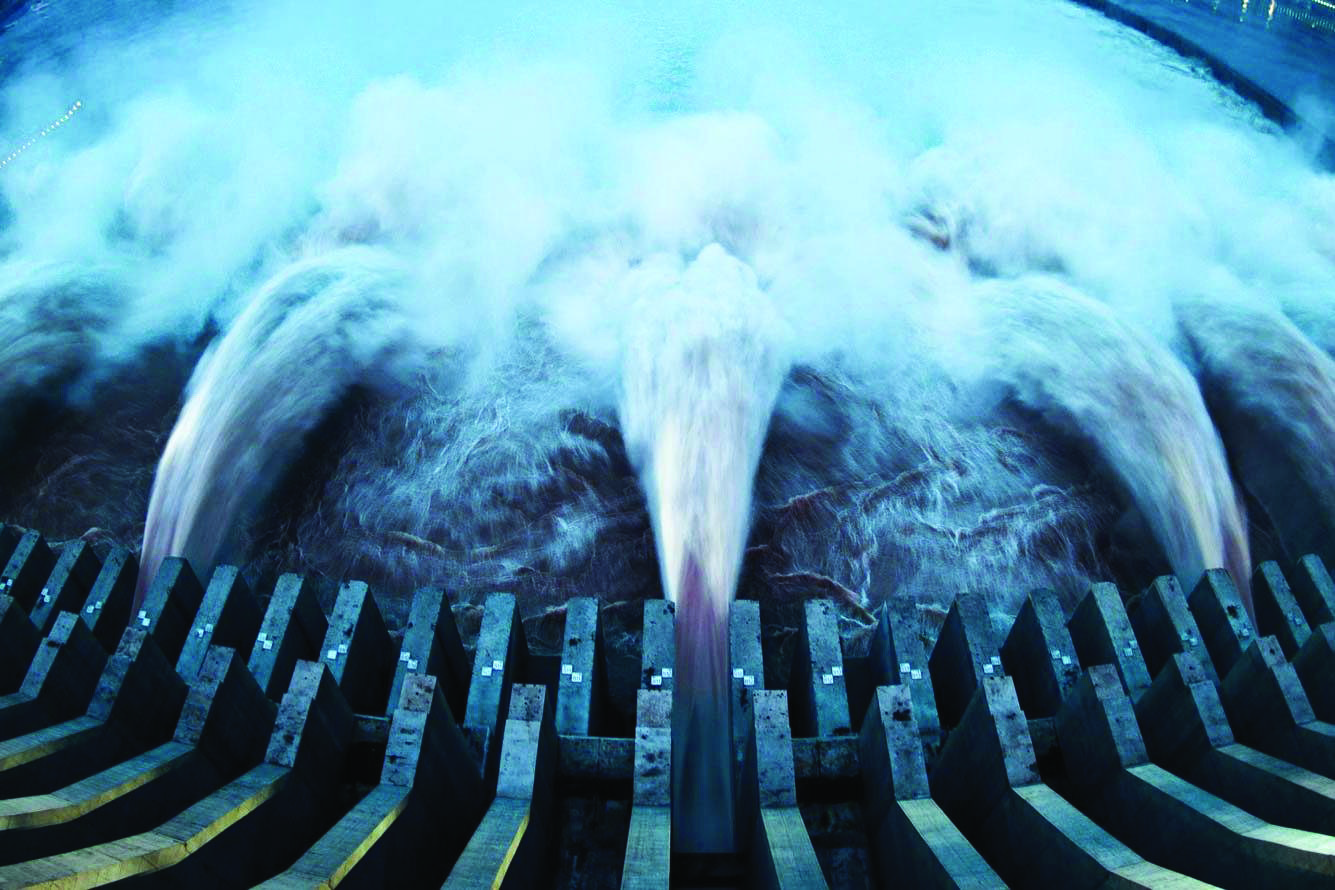

River governance, particularly under the Namami Gange Mission, has moved from symbolic clean-up drives to measurable infrastructure and treatment capacity creation. The establishment of the National River Research Centre mark a transition towards data-driven, basin-level planning. Still, challenges persist in urban wastewater compliance, inter-state river coordination, and maintaining ecological flows beyond major project corridors. Stronger regulatory enforcement and basin authorities with operational autonomy could further strengthen outcomes.

Overall, India’s water governance is clearly on the right trajectory, but the journey to a truly water-secure Viksit Bharat requires sustained institutional reform, policy convergence, and behavioural change. The task is ongoing, and success will depend on consolidating gains, addressing regional disparities, and embedding water sensitivity across agriculture, urban planning, and industrial growth strategies. If the current momentum is sustained through deeper reforms and adaptive governance, water can emerge as a central pillar of Viksit Bharat 2047, strengthening India’s developmental resilience, ecological security, and long-term inclusive growth.

Rakesh Singh is Managing Editor, ITV Network