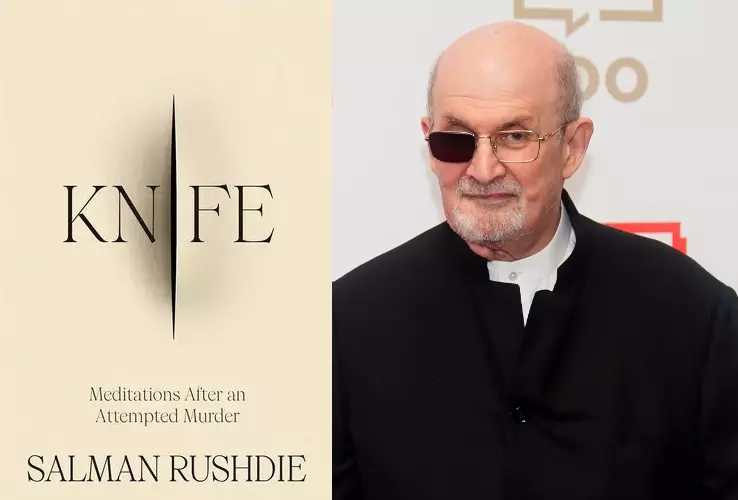

Salman Rushdie’s ‘Knife: Meditation After an Attempt Murder’ (2024) is a collection of autobiographical memoirs. He wrote the memoir after he was attacked on 12th August 2022 in New York where he lost his right eye in this attack. He dedicated this book to the men and women who saved his life. He insisted that he had to write this memoir, otherwise he would not be able to write anything else. This memoir has been written in a first-person narrative. He says, “That’s an “I” story. And now, I tell myself, it’s also an “eye” story.” But his eye story is focused on the issues of obscurantism and barbarism and a number of hidden threats to humanity, narrow-minded religious discourses which misled youth in the contemporary period.

Moreover, he believes that the artist can answer violence in some artistic idioms because he or she has trained his mind to change the world with words and language. So words are his powerful weapon against violence. Salman writes, “I don’t like to think of writing as therapy-writing is writing, and therapy is therapy- but there was a good chance that telling the story as I saw it might make me feel better.” Here he is very clear about the difference between, the ‘therapy’ and ‘writing’ but in spite of that he starts meditating with words and number of references and quotes which was focused on the ‘knife as metaphor of hate’ and that meditation was for his literary world. Through the medical treatments, they were healing him physically, but the meditation of the words was healing his creative mind only through addressing the problems in depth and detail. As he believes that language is his ‘knife’ in all circumstances, that is why he could create a wonderful artistic work with it.

‘The A’ is the person who attacked him fifteen times with a knife in twenty-seven seconds. He wanted to murder him because he thought that Salman was a ‘disingenuous’. Salman did not make any straight comment on the A’s cast, creed or community, and any traditional identification is not labeled with the attacker. He simply addressed him ‘the A’.

Because he does not want to spread hate about a particular community, a mature reader understands his limitations. If he discloses A’s community directly, it may deliver a wrong message and irrational hostility towards that community. Salman arranged an imaginary meeting with ‘the A’. He says, “Because a real meeting is improbable-make that impossible- I have to imagine my way into his head.” This imaginary meeting is the most interesting part in this book because, through this dialogue method which is concluded in four sessions, he genuinely wants to understand how the modern technology is going to encourage the young minds for unkind and unlawful activities in the “disinformation age”.

He believes that young minds are being trapped by religion, even a twenty-seven-year-old ‘the A’ who was inspired to kill an old and a strange person without understanding his philosophy of life and ideological approach, but based on some YouTube videos. Because ‘Yutubi noise’ had made it possible for ‘the A’ to pick up the knife. The conversation proved that the attacker could be asked such questions which he or his like-minded people might have no reasonable answers to the questions. Religion versus reason, knife versus knowledge and hate versus hope are the main themes of this book.

When Salman talks about religion he becomes very cognizant and conscious. He states that we have to distinguish between private religious faith and public politicised ideology. Consequently, ‘it would be easier to see things as they are and to speak out without worrying about offended sensibilities.’ Because from the very beginning, he advocates freedom of speech. Even when he was attacked in Chautauqua, he was invited there to deliver a lecture on the theme of ‘Freedom of Speech’. He says, “I have no issue with religion when it occupies this private space and doesn’t seek to impose its values on others. But when religion becomes politicised, even weaponised then it’s everybody’s business because if its capacity for harm.” So a secular approach has been adopted. His faith in creativity was more determined after this attack. Now he has two aims in life: love and work. He determines himself by saying that ‘If you are afraid of the consequences of what you say, then you are not free.’

But before this attack, though he believed that it had been thirty-three and half years since Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s notorious death order against him, because it was said that Salman had made some objectionable statements in his fictional writing ‘The Satanic Verses’ (1988) that set a Muslim community leaders were against him and innumerable condemn action and criticism were there against the said fictional work. But Salman believed that the world had moved at its own speed and that the subject was ‘closed’. But a ‘murderous ghost’ from the past in the new generation was approaching him in its own way with a traditional weapon, i.e. a knife. Even Salman’s subconscious mind was dreaming a blinking message of attack in the form of a dream and he saw the same dream two nights before the actual attack in Chaurauqua. His readers all over the world were praying for him, but he was so confirmed in his beliefs about godlessness and didn’t believe in any miraculous powers, so he did not recite any prayers to God in those critical conditions. He says, “My godlessness remains intact. That isn’t going to change in this second-chance life.” There were even six assassination plots against him in the years after Fatwa, but all were foiled by the expertise of the British intelligence services. Though the fear of an attack remained in his mind and sometimes interviewers asked this uncomfortable question to him. But he sardonically answered every time. Even after the attack, he says during the treatment days that his waking self was calm, collected, optimistic and determined, but the wild nights of dreams told the truth and all the horrors came back to his mind. But he kept fighting with strong will-power. The reader can imagine how he is mentally strong because of his jovial mood. His ‘near-death experience’ in Chaurauqua is so vivid and vibrant that nothing is metaphorical or supernatural about it. Rather, it is very rational and well-narrated, a collection of real incidents.

The Knife’s ending is very artistic. Salman and his wife Eliza are coming back home after visiting the palace where Salman was attacked. He and his wife were on the same stage of the amphitheater and stood there and held each other tightly and told each other ‘We are together, I love you. I love you too’. They had come through the nightmare, but now they were feeling a new life. “We’re done here,” he said to Eliza, taking her hand. “Let’s go home.” The last single sentence conveys a message of life and love. It is a thought-provoking statement about a writer who has been facing a harsh reality of his life and even a threat was there. He did not leave his hope for better days and a bright future. This book inspires the readers to live life jubilantly with vitality and be optimistic in any circumstances.

Developed and underdeveloped countries face religiocentrism, which is a big problem in contemporary societies of the world. Though Salman does not directly address the problem of majoritarian Hinduism in the Indian administration, he states that ‘India is sinking fast into authoritarianism’. Along with this, he reminds us of the aftermath of the bloodbath of the partition massacres where thousands of innocent people had lost their lives because of their religious identities. So he indicates that secular values and rationality can help us to make the world better and language and the arts can play an important role in it.

All the best Salman for your ‘left eye’!

Dr. Satinderpal Singh Bawa is Lecturer in Punjabi, GSSS Bhagal Kaithal Haryana (India) and he has got published two books in Punjabi Criticism. He frequently writes in Punjabi and English.