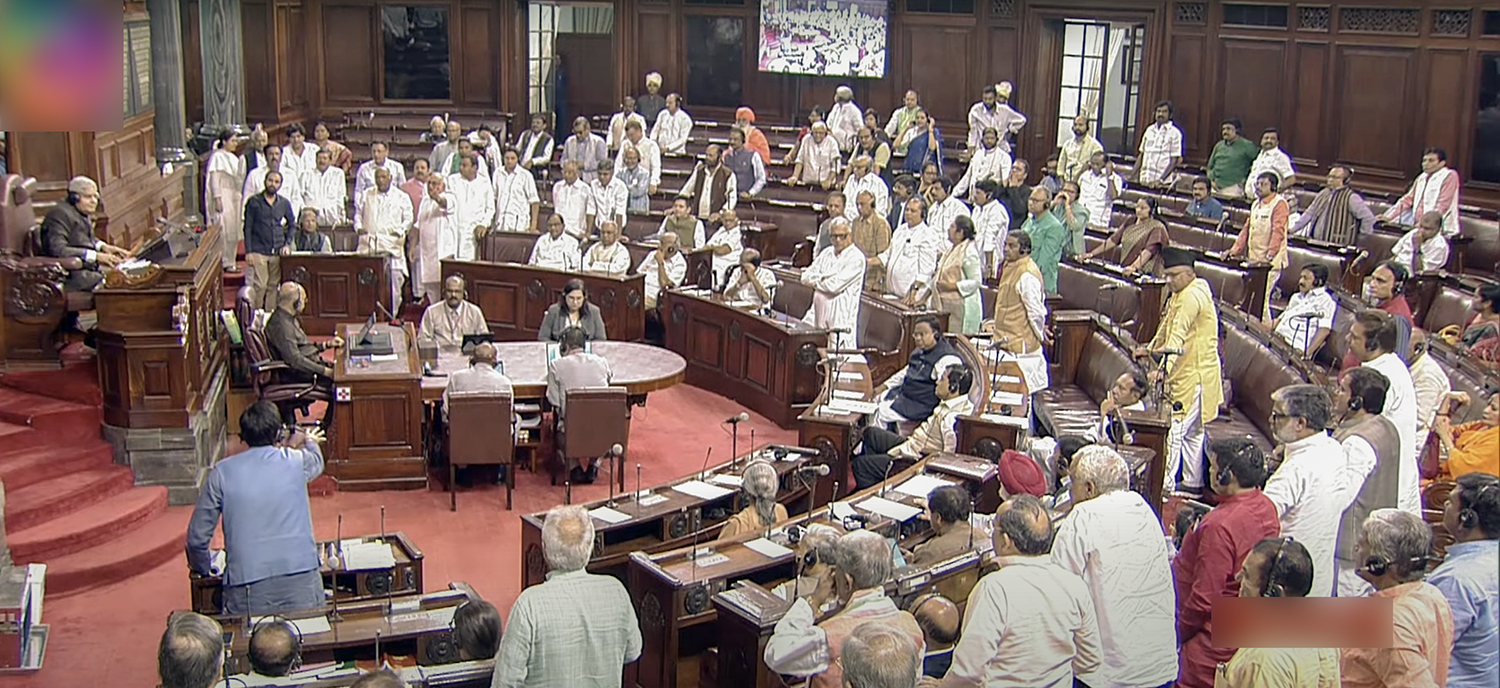

The admission of the motion of No-Confidence in the Council of Ministers by the Speaker would hopefully bring normalcy in Parliament. It may also, in all probability, take the wind out of the sails of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha as well. The notice of the motion has been given by Gaurav Gogoi of the Congress reportedly enjoying the support of 26 parties in alliance. A motion of no-confidence in the Council of Ministers can be brought only in the Lok Sabha. Article 75 of the Constitution provides that the Council of Ministers shall be collectively responsible to the House of the People. Rule 198 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in the Lok Sabha contains the procedure regarding no-confidence in the Council of Ministers. Notably, for admission of Questions, Motions or Resolutions, there are elaborate rules governing their admissibility or otherwise. But in the case of a notice of no-confidence motion, “the Speaker shall read the motion to the House” if he finds it in order. The Speaker may reject the notice of a motion outright if it is not properly worded without reading it to the House. But if in the opinion of the Speaker the notice of motion is in order—as the Speaker found it in the present case—he is duty bound to read it to the House and if not less than 50 members rise in their places in favour of the leave being granted, the Speaker declares that the leave is granted. The motion for discussion is taken up on such day as may be decided in the Business Advisory Committee or in the meeting of the leaders of political parties chaired by the Speaker himself. However, the Rule provides that the discussion must take place within 10 days from the day the leave was granted. Normally, the discussion on the motion takes place within a few days once the motion is admitted.

Contextually, in the Rajya Sabha, the Opposition has been persistently demanding a discussion on the Manipur situation under Rule 267 instead of under Rule 176 for which the government was willing to have a short duration discussion of two hours and half. The hunch of the Opposition was that by accepting a short duration discussion, it will give an escape route to the government and that the Opposition would not get adequate time to articulate their concerns. Further, the Opposition wanted the Prime Minister to make a statement in Parliament instead of the Home Minister, though there is no rule as such requiring the Prime Minister to make the statement. The Council of Ministers is collectively responsible to Parliament and any minister can make a statement on behalf of the government, though by convention it is the Minister in-charge of the subject who replies in Parliament, which in this case is the Home Minister.

Now that a motion of no-confidence has been accepted by the Speaker, the discussions on the motion will provide ample opportunities to the Opposition to corner the government on all fronts, including the situation in Manipur. Equally, it would give a great opportunity to the treasury benches to train their guns at the Opposition and the (alleged murky) state of affairs in the provinces ruled by them. The discussions on the motion is free for all, subject to the general rules of the debate. All sections of the House—political parties and groups—get time proportionate to their numerical strength in the House within the time allocated. The mover of the motion would be speaking first in support of his motion followed by the treasury benches and other political parties and groups in turn. The leader of the House-the Prime Minister being a member of the House, replies to the charges levelled against the government. The mover of the motion has the right to reply. This is followed by voting in order to determine the decision of the House on the motion. The Prime Minister invariably replies to the charges levelled, being the keystone of the cabinet arch. However, on 8 May 1998, in the absence of the Prime Minister who was on a State visit abroad, the charges levelled by the Opposition were replied by the Finance Minister.

From First Lok Sabha to the Seventeenth Lok Sabha till date, there have been 28 (the instant one including) motions of no confidence. In addition, a peculiar case is of the Fifteenth Lok Sabha when many members of the ruling party tabled notices of no-confidence motions which were not taken up by the Speaker (Meira Kumar), on the ground that the House was not in order. Besides, there have been 12 motions of confidence in the Council of Ministers which were brought before the House by the ruling party. Three prime ministers—V.P. Singh (1990), Deve Gowda (1997) and Atal Bihari Vajpayee (1999) —lost the no-confidence motions. A no confidence motion against Morar ji Desai in 1979 triggered his resignation before the motion could be put to vote. Indira Gandhi faced 15 such motions and lost none in her 16-year tenure. The fate of the second no-confidence against the Modi government., like the first in 2018, is obvious, given the overwhelming majority of the treasury benches. The naive question asked is what is the point of bringing such a no-confidence motion with a sealed fate. The mover of the motion and those in support of it, know it so well. The real intent and objective of the mover of the motion invariably is to make an all-out attack on the government for its alleged acts of omission and commission and present a picture of failures and misdeeds of the government to the people. But there is more than equal opportunity to the government to highlight its good works. It’s an occasion for fine and florid debate which may soar to sublimal heights occasionally. In fact, some of the finest debates took in Parliament on such motions, including the motion the Vajpayee government lost. Let the nation watch the debate and let “we, the people”—the eventual jury—distinguish between the chaff and the grain, between the hollow and spurious and solid and substantive arguments.

The author is a former Additional Secretary, Lok Sabha, and a Member, Delhi Bar Council.