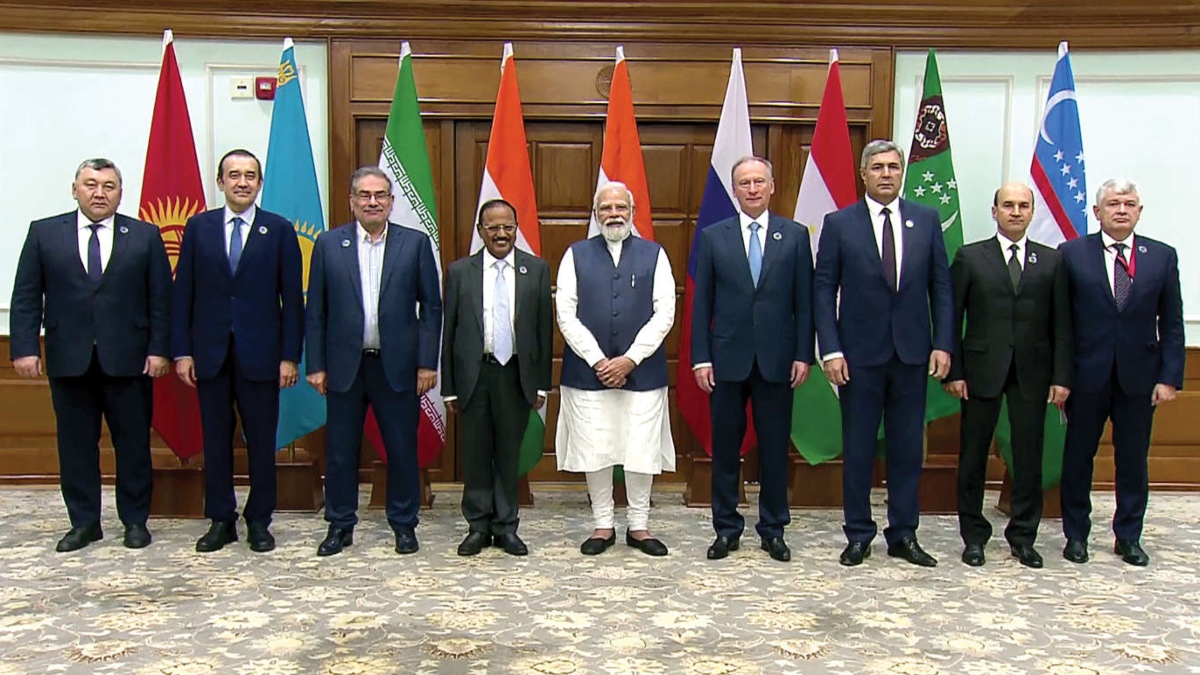

The Regional Security Dialogue on Afghanistan, a conference of the countries in the neighbourhood of Afghanistan— convened at the level of National Security Advisors at Delhi on November 10— to discuss the Afghan scenario has been an extremely successful move by Ajit Doval, our National Security Advisor. It effectively served the three-fold objective of creating a broad convergence amongst countries with security stakes in Afghanistan on the demands of democratisation that the Taliban regime must fulfil, raising the issue of ‘radicalisation’ as a threat to the region and specifically calling upon the Taliban government to ensure that Afghan territory was not used for terror activity. India appropriately invited Russia but not the current regime of Afghanistan which was the very cause of concern on the agenda of the Delhi conference.

Both Pakistan and China, though invited stayed away, the former questioning India’s credentials for holding the meet and the latter falling in line with Pakistan because of the sheer compulsion it has for being with that country in pursuance of its larger geopolitical strategy. Their absence only helped to draw the attention of the meet on the collusive role of the Sino-Pak axis in reestablishing the Taliban rule in Afghanistan. As far as US is concerned, India shares a commonality of views with it on the Afghan situation, and considering the fact of the American pullout from that country having taken place in an embarrassingly messy environ marked by hostility of Taliban— in spite of the Doha agreement— it is as well that the US was not involved with the event. US would in any case welcome India’s initiatives on Afghanistan.

Afghanistan under the Taliban Emirate is a global security problem more than a diplomatic issue as the democratic world was still pondering over the question of giving recognition to this regime in the first place. The central Asian republics around Afghanistan who all responded to India’s invitation—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan— are predominantly Muslim states that were attuned to a life of moderate Islam and were running the risk of being overtaken by radicalisation if Taliban were to have a free run in Afghanistan. During the Cold War, Pakistan, a great ally of the West then, was used by the US for injecting Islamism in the Communist-controlled territories of Uzbekistan and Xinjiang on the border of Afghanistan through outfits mentored by ISI. These Islamic forces— Jamaat-e-Islami’s front Hizbul Mujahideen (HuM) and Saudi-funded Lashkare Toiba (LeT) later led the anti-Soviet armed campaign in Afghanistan that was subsequently joined in also by radical outfits like Taliban and Al Qaeda. The central Asian countries participating in the conference of NSAs at Delhi— and they were present in full strength— realise that they were vulnerable to the disrupting influence of the Emirate installed next door by Pakistan with endorsement from China. Russia and India are on the same page, in not letting that happen. India has done well to invite Iran because regardless of Iran’s troubles with the US and Israel, the acute hostility of the radical Taliban towards Shias put Iran on the side of India on Afghanistan.

The conference labelled as the Regional Security Dialogue on Afghanistan adopted the ‘Delhi Declaration’ that reaffirmed the commitment of the participating countries to combat terrorism in all its forms and manifestations including its financing, work for dismantling of terrorist infrastructure and counter ‘radicalisation’ to ensure that Afghanistan would never become a safe haven for global terrorism. Expressing ‘deep concern’ over the deteriorating socio-economic and humanitarian situation, that underlined the need for providing urgent assistance, the Declaration pointed to the critical need for establishing ‘an open and truly inclusive government’ in Afghanistan that had representation from all sections of the Afghan society. It laid emphasis on the fundamental rights of women as well as those of children and minority communities. The statement was as comprehensive and complete as the democratic world have wished it to be and goes a long way in securing an international disapproval of the rise of Islamic extremism and radicalism that the return of Kabul Emirate signifies.

The event would help the two largest democracies of the world to lead the global combat against this dangerous development. Biden administration is currently focused on dealing with the Communist dictatorship of China in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere in the face of the express intent of President Xi Jinping to make his country the second superpower— in the process it seems to be overlooking the Sino- Pak strategic partnership that had become a notch deeper since the emergence of Taliban in Afghanistan. The US needs to have a closer look at the significance of a Communist regime and a country standing by Islamic radicals, coming on the same side politically in the emerging ‘Cold War’ between US and China.

In addition, herein perhaps lies one of the reasons why Pakistan has predictably responded to India’s regional initiative on Afghanistan by calling a meeting of the big three— US, Russia and China at Islamabad close on the heels of the Delhi summit, to which the foreign minister of Afghanistan Emirate has also been invited. Pakistan knows that because of its role in Afghanistan it is on a discount in the eyes of the countries of this region. It has however sensed that Biden Presidency still valued its friendship for its mediatory role in Doha negotiations and its importance for the Saudi-led block in the Muslim world that was pro-US. Policy makers in US do seem to be taking cognisance of the duplicitous play of Pakistan in the ‘war on terror’ that was essentially a straight fight between the US-led West and the Islamic radicals. They must also be analysing the implications of the Sino-Pak collaboration for the emerging geopolitics. India is playing its cards well in dealing with Pak-Afghanistan belt on one hand and countering China’s aggressiveness both on the border and on the marine front, on the other.

The writer is a former Director of Intelligence Bureau. Views Expressed are writer’s personal.

Both Pakistan and China, though invited, stayed away— the former questioning India’s credentials for holding the meet and the latter falling in line with Pakistan because of the sheer compulsion it has for being with that country in pursuance of its larger geopolitical strategy.