Bold and transformative steps are required to change the way poverty is handled to ensure that no-one is left behind on India’s path to prosperity. Since poverty is an outcome of household ecosystems, the establishment of a comprehensive universal database of individuals and households to overcome silo-based fragmentation in government delivery of anti-poverty programmes and services is essential for the paradigm shift necessary to move from a welfare approach to one of entitlement. This universal database ensures that no one is left behind and assistance is delivered as per eligibility. Realtime data is ensured through this live population register of events in every household like births, deaths, any split in family, migration, addition or shift due to marriage etc. thus making repeated surveys unnecessary. With links to individual accounts at financial institution within a five kilometre radius, this database would enable direct social protection transfers.With all departments working on the same database, the issue of multidimensional and multisectoral approaches would be eliminated and, the data being time series records, informed policy making and targeted interventions will be ensured.

SAMAGRA in Madhya Pradesh has since 2012 adopted this methodology of having a Common Household Database with each intervening assistance being managed and monitored through the same database. Eight other major federal states in India have also adapted this process. The method’s feasibility and importance are clearly demonstrated as well in Telengana as Kutumbh Samagra, and in Rajasthan as Bhamasha etc. Atan all India level,the National Scholarship portal and the Ayushman Bharat health scheme have also been developed on this basis. Neighboring countries, like Bangladesh, have utilized the same method. Many developed and developing economies have also accepted the need to break the silo approach and have made a beginning by merging a few of their existing data bases.

This paradigm shift in the approach to poverty as a multidimensional and multi-sector problem and the use of a common household database ensures sustainable outcomes for the eradication of poverty in all its forms and dimensions, and this entitlement-based approach ensures that no one is left behind. Global partnerships are advocated through assistance and handholding to develop this common household database to optimize scarce resources and to ensure that interventions and policies lead to sustainable higher incomes, access to opportunities and an acceleration in the pace of change for the betterment of lives.

A common household database approach not only enables major transfer programmes in every state to be monitored simultaneously at the household level, it also underpins the paradigm shift from a demand led to an entitlement-driven approach for the delivery of benefits. It reduces fragmentation and improves quality and efficiency in household surveys by providing a single, unified population monitoring system through real time recording.

All the work of capturing verified parameters for the household database with details of individuals of being below poverty line, caste, gender etc. led to the emergence of SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals) with a clear objective and a new development agenda in 2015 with the bold intention that ‘no one is left behind’ and leading to sustainable development to be achieved by 2030. “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity. It also seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom. We recognise that eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions, including extreme poverty, is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development. All countries and all stakeholders, acting in collaborative partnership, will implement this plan. We are resolved to free the human race from the tyranny of poverty and want and to heal and secure our planet. We are determined to take the bold and transformative steps which are urgently needed to shift the world onto a sustainable and resilient path. As we embark on this collective journey, we pledge that no one will be left behind. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals and 169 targets which we are announcing today demonstrate the scale and ambition of this new universal Agenda.”

The key words of the resolution are: 1. Sustainable Development is an indispensable requirement 2. Eradication of poverty in all its forms and dimensions 3. Collaborative partnership 4. Determination to take bold and transformative steps 5. Most importantly, ensure that no one is left behind.

The governance models developed over past six decades, with an increasing focus on the rights agenda, have had a different focus over a period of time resulting in a silo approach towards health, poverty, sanitation and water, livelihood opportunities etc. The effort has been to provide basic needs only. The discourse was limited to just survival at a subsistence level. The endeavour has been to ensure the availability of basic needs like food and shelter, health, education i.e. to survive and this therefore was not sustainable and was aid dependent. Even though it had an impact on poverty reduction, it did not pave the way for the eradication of poverty with the most vulnerable often being left out or being unable to access the complete package. The global impact of any disaster pushed them back into the poverty trap and resulted in more and more deprivation.

The new development agenda flags sustainable development as an indispensable requirement, the keyword being sustainable i.e. the development of an ecosystem and the capacity to optimise opportunities for enhanced income levels to ensure wellbeing. Hence, if eradication of poverty in all its forms and dimensions is intended then there is a need to have a major paradigm shift from the silo approach to that of the Common Household Database (Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 1 to 7). As this data will be universal, it will enable policy makers, implementers, assistance givers and household members themselves to have a comprehensive need analysis and thus interventions that are targeted accordingly. That can be achieved only by taking this bold and transformative step coupled with a systematic approach to prevent the effort from becoming mere rhetoric. This enables a holistic approach to the household for ensuring opportunities for them for sustainable growth and be out of poverty.

Can the SDGs be achieved by 2030? Overseas Development Institute (ODI) has projected how the world is likely to do on all 17 SDGs, based on current trends. While performance across the goals and in each region is likely to vary widely, current global performance is heading towards failure on all the SDGs, come 2030.

Thus, the challenge is to have a relook at the approach that has been adopted so far and changing to a system based approach not just to achieve outcomes, but also to ensure that the efforts and results are sustainable.

Another challenge is how to accelerate the pace since the accepted deadline is 2030. The commitment is a recognition that the countries have to develop policies and methodologies targeting zero tolerance for continued poverty and its related issues. It is a commitment to not only initiate but modify efforts to ensure that the outcomes are not a one off but are sustainable. The time left is now only eleven years.

How silo data has hampered inclusive approach limiting benefits to only those who approached and leaving out the most vulnerable who had no access: The Harvard Business Review analyses the silo evolution as it was done to the limited extent of intended use based on a desired application.You need to format, filter, and manipulate the data accordingly. Every new problem led to again repeating the exercise of data acquisition and preparation. It refers to data silos as demons. These silos are isolated islands of data, and they make it prohibitively costly to extract data and put it to other uses. They can arise for multiple reasons. The reasons flagged are structural as software applications are written at that point in time with the inbuilt issue of vendor lock-in, political in terms of knowledge being power and therefore a reluctance to share. Then the cost factor as it is costly to reconcile and integrate sets of data that embody different approaches to important business concepts. The study, though done for business houses, is equally applicable to the social protection efforts as eradication of poverty needs a business approach.

Why bold and transformative steps to shift to common household data base is the need of the day

With intention and commitment to move to higher value uses and to be effective in delivery mechanisms the need is to break the silos and shift to having common household database for the listed agenda of eradication of poverty in all its forms and dimensions.

It is equally important to not start from scratch by resorting to fresh surveys but to build upon the largest existing available data base in that country. Definitely, a “data lake” is not the answer as we just can’t pour all our data into one system, expecting goodness to result. The issue is to evolve a database that is all comprehensive allowing navigation to entitlements so that it can be worked by multi-users simultaneously through different vertical columns.

Every incident in the household thus gets captured enabling real time assessments. This paradigm shift is the bold and transformative need of the day to ensure that no one is left behind.

Can the SAMAGRA approach be transformative?

James Ferguson, in ‘Give a man a fish’ analyses how cash transfer programmes to address extreme poverty and inequality. Cash transfersfirst require the capture of entitlements due to households and its individuals so that no one who is eligible is left behind. A SAMAGRA approach enables this process and then allows direct benefit transfer in the most transparent way. The data also enables the capture of the socio-economic status of the household and enables a spread sheet of income from all sources to assess basic income criteria. The approach is equally relevant to developed economies that may not be battling absolute poverty but do have serious concerns about inequity, environment and climate. Migration due to abject poverty or lack of opportunities in the country of origin is also of concern for developed economies and thus there is need for transferability and a handholding approach to develop mechanisms to evolve a common household database strategy through partnerships that will be symbiotic.

Thus, the moot question is how to move towards having a common household database and then ensure monitoring as a time series and real time data for multidimensional progress from poverty to prosperity (PtoP). The challenge is to have data that enables the capture different interventions by multiple government agencies and civil societies that either directly transfer the benefit or create an enabling environment for growth that is sustainable. SAMAGRA in Madhya Pradesh is a good is example to understand how adopting the SAMAGRA approach makes these objectives achievable both for developed and developing economies.

Understanding SAMAGRA (a common household database) approach of Madhya Pradesh

There was a conscious thought process to develop a methodology and mechanism to rationalise existing schemes, improve entitlement-based systems and then resort to a systemic change using a common household database—the SAMAGRA approach. It is doable, and has has been successfully done in the state of Madhya Pradesh and is being adopted by other federal states like Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan and Haryana is in the offing, in very short span of time of just four months. It has been documented by UNDP India as a Samruddhi experiment (Jan 23, 2014 UNDP Samruddhi in India: the Madhya Pradesh model of financial inclusion www. in.undp.org/…/samruddhi- –the-madhya-pradesh-model-of-financial-inclusion.pdf) and by PWC’s (Price Waterhouse Cooper) case study on SAMAGRA (SAMAGRA Portal Initiative to Implement Integrated Social Security Programmeand Direct Benefit Transfers by having a Common Household Database) and now at IIT Indore. UNICEF is documenting the process for making it a Social Registry as SAMAGRA 2.0. Many developed and developing economies are planning a shift towards the concept of having a common database. SAMAGRA: Comprehensive Common Household Database (the running portal can be viewed at Samagra.gov.in)

Why transform to common household data base?

Challenges faced before SAMAGRA: Unfortunately, even though the beneficiaries are households or individuals in households, the data stored was in silos.Each department had done independent surveys, digitized their data and had different timelines for updating the data. The data was only of those that were being benefited in that particular scheme, and there was no database of those who were left out, there was no universal data base. There were issues of benefits being cornered by a few and many a times the seeking double benefits. Thus, while it is awelfare measure,it did not have any mechanism to measure how many people were left out and did not receive their entitlements.

Multiple departments offering similar, overlapping, repetitive schemes leading to waste of resources: While various departments offer similar schemes targeting different categories of people, the job-portability factor means that the targets are often common and individuals may end up benefitting from all – or several – departments. In fact, since there is no monitoring system, there is no clarity on whether a person has actually received the benefits from one or many departments or not received any benefit at all. So there is possibility of multiple departments booking their expenditure against the same beneficiary, resulting in a statistical misrepresentation that could lead to skewed estimates and strategies. After execution of SAMAGRA there have been empirical evidences in removing duplication and reaching the beneficiaries who were entitled but left out in distribution of scholarships and bank subsidies for development loans.

Lack of coordination between departments, schemes and the mapping of beneficiaries

The lack of coordination between various departments leads to an overlapping of benefits and beneficiaries among similar schemes. All the departments might be maintaining a list of their beneficiaries under various schemes but there is no single unique identifier and no sharing of data. Aadhaar is a unique individual identifier in India and needs to be seeded physically in every existing data base. Also, the entitlement and benefits come because of family status and that is not captured in Aadhaar. The family has to be Below Poverty Line, the employment guarantee of 100 days is to the family, the scholarship entitlement to individual children if the family is BPL (Below Poverty Line) or belongs to a particular caste, class of housing, so on and so forth. Thus, even unique individual Aadhar numbers were not sufficient for administrative requirements to ensure poverty targeted interventions, ensuring minimum basic income and also health and sanitation care. The SAMAGRA approach recognizes the fact that comprehensive household status does have an impact on the individual.

Similarly, there is a lack of effective monitoring, control and evaluation even within the departments. While most departments have got the list of their schemes including the beneficiaries digitized, in most cases, the data only comprises numbers and not the names of the beneficiary. Thus, while the expenditure is booked, there is seldom any proof of the subsidies/benefits being actually transferred to the deserving beneficiaries whether in cash or in kind. There is also no evidence of who were left out.

Multiple agencies insuring the same person

The preparatory study of SAMAGRA reports have found that there were multiple subsidies (for example insurance) allocated by the state government to target a single coverage for social security. Worse, often the beneficiary/resident was not even aware of all the benefits booked for him or her. Lack of knowledge of the entitlements by the beneficiary resulted in no access. This resulted in a drain of resources, with the government giving multiple premiums for the same persons to certain agencies and beneficiaries failing to access the benefits.

Multiple registrations of beneficiaries and non-sharing of data

SAMAGRA during its formulation has flagged that certain bodies and agencies like the Building and Other Construction Workers Board, formed under the aegis of the LabourDepartment, have collected cessintoa corpus and have also registered workers under its purview in order to implement schemes under which they are entitled to receive certain benefits- -however, the same benefits are also being provided under different schemes of the Women and Child Development Department. This duplication happens because the data is neither shared nor integrated.

No accountability and transparency

The implementation of these schemes in a proper and transparent manner poses a major challenge as the entire process of repeating surveys and updating is carried out manually and in an isolated manner. There is little accountability and transparency in such a system and citizens find it difficult to avail benefits of schemes intended for them in a prompt and hassle-free manner. The manual system with different databases creates a hindrance for any systematic approach.

Multiple service delivery points for similar schemes

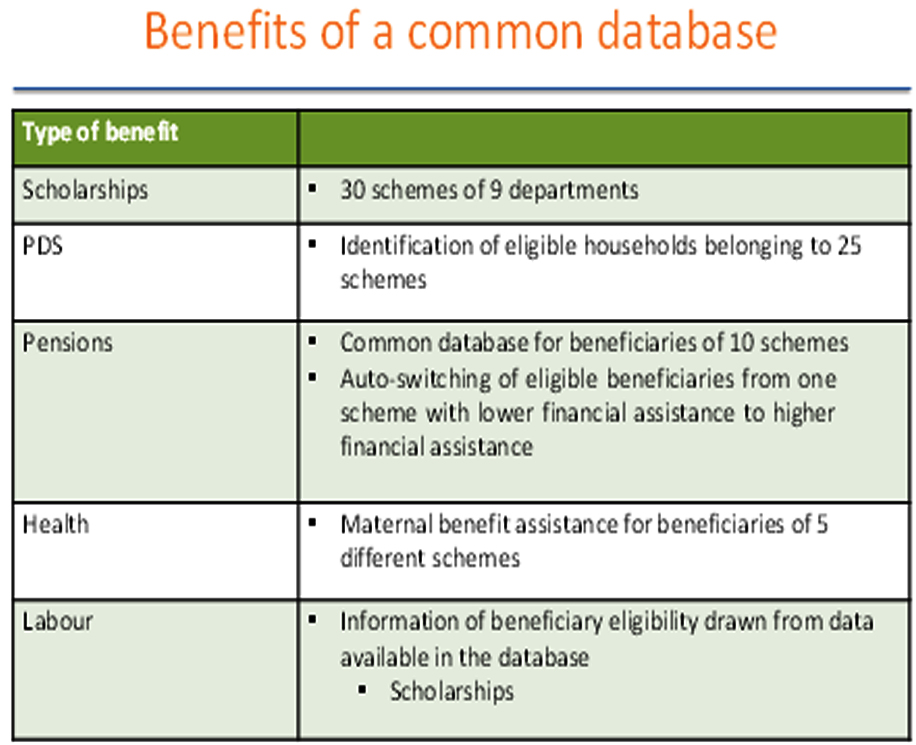

Those in need of a specific service have to approach multiple offices for seeking the benefits of various schemes for which s/he is eligible. Let us take the example of maternity benefits: one has to approach the health department for some services, the labour department for wagecompensations, and so on. SAMAGRA has evolved as a panacea after realising the above issues, through discussions held across departments. Empirical data with illustrations was provided listing the number of departments that give benefits for housing, scholarships for children, maternity benefits, assistance in cash and kind to solemnise marriages of daughters, assistance to the differently-abled in terms of medical, income support, equipment and insurance etc. The double benefit cases were presented to the then cabinet of ministers Madhya Pradesh who approved the switch to using a common household database and now each department works on the same data base.

(To be concluded)

Dr Aruna Sharma (IAS) is a development economist and has served as Secretary, Government of India