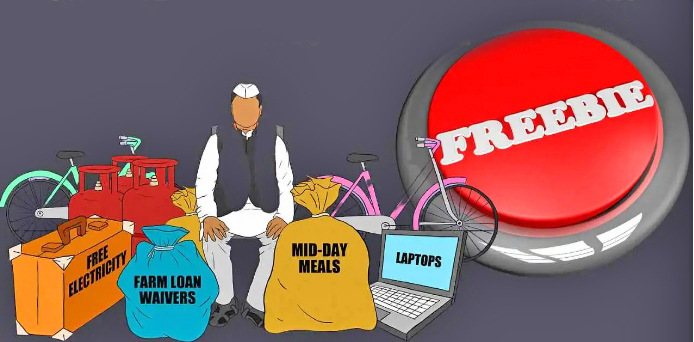

As India enters another election cycle, the familiar language of freebies is already dominating political discourse. Free electricity, subsidised goods, cash grants and other handouts are being promoted as welfare. These promises may feel good in the moment, but they are draining state finances, creating dependency and diverting money from investments that build real economic capacity such as schools, hospitals, infrastructure and jobs.

To be clear, welfare is vital. Investments in education, healthcare and infrastructure allow citizens to participate in the economy, raise productivity and reduce poverty. True welfare builds capacity and expands opportunity. Freebies, on the other hand, are consumption transfers with no long-term return. When state budgets are crowded with recurring subsidies, capital expenditure, which creates future growth, is squeezed.

The political incentives behind freebies are obvious. Immediate benefits are easier to communicate and more likely to secure votes than long-term reforms. A cash transfer shows up instantly in a bank account; a new school or hospital takes years. Over time, this creates a bidding war of promises and rewards based on short-term gains rather than sustainable development.

This strategy has delivered electoral dividends in several states. In Maharashtra, welfare and direct benefit schemes have been central to election campaigns for years, shaping voter behaviour even as the state’s fiscal stress limited spending on infrastructure. In Bihar, the practice has become particularly striking. Ahead of elections, the state government announced cash transfers of Rs 10,000 to beneficiaries, a move widely criticised as politically timed and resembling an inducement. In a state with deep structural economic challenges, such large public cash disbursements erode the fiscal space necessary for building industrial capacity and jobs.

At the national and city level too, welfare narratives have played a significant political role. In the Delhi Assembly elections, the BJP manifesto promised Rs 2,500 per month to eligible women under the Mahila Samridhi scheme. If fully implemented, this would cost the Delhi government an estimated Rs 11,000 crore annually, given the potential scale of beneficiaries. Months after forming the government, the promised payments have yet to materialise, highlighting the gap between electoral rhetoric and fiscal reality.

The scale of such promises invites comparison. Even a fraction of Rs 11,000 crore could be used to meaningfully address Delhi’s pollution crisis. High-quality air purification systems in schools and hospitals, expanded public transport, stricter emissions enforcement, and increased urban green cover would deliver measurable health and productivity benefits. Instead of locking large sums into recurring cash transfers, targeted environmental investment would improve quality of life for millions.

The problem is not only that freebies are expensive. It is that they are often unfunded and announced without clear financing plans or sunset clauses. When budgets are strained, education, healthcare and infrastructure suffer. Debt rises, and future governments inherit shrinking fiscal space.

This is where judicial scrutiny becomes necessary. The Supreme Court has already been asked to examine the legality and fiscal prudence of freebies. A suo moto intervention would not amount to policy-making. It would enforce transparency and accountability. The Court can require that major election-time promises be accompanied by audited fiscal impact statements, clear funding sources, measurable goals and defined timeframes.

Such measures would strengthen democracy by enabling informed choice. Elections should be about competing visions for growth and opportunity, not about who can offer the most expensive handout.

There is a constructive alternative. Redirecting even part of the money spent on open-ended freebies toward education, healthcare, infrastructure, skills training and pollution control would generate long-term returns. Targeted, time-bound cash support can remain for the vulnerable when linked to outcomes such as school attendance or employment transitions.

Freebies may win votes, but they weaken the foundations of the economy and democracy. India cannot afford a politics that trades long-term growth for short-term applause. The Supreme Court has the authority and responsibility to draw a clear line between genuine welfare and electoral inducement. That line must be drawn now, before fiscal populism becomes irreversible.

Shivam Bhagat is Spokesperson, Indian National Congress. Views expressed are personal.