INTRODUCTION

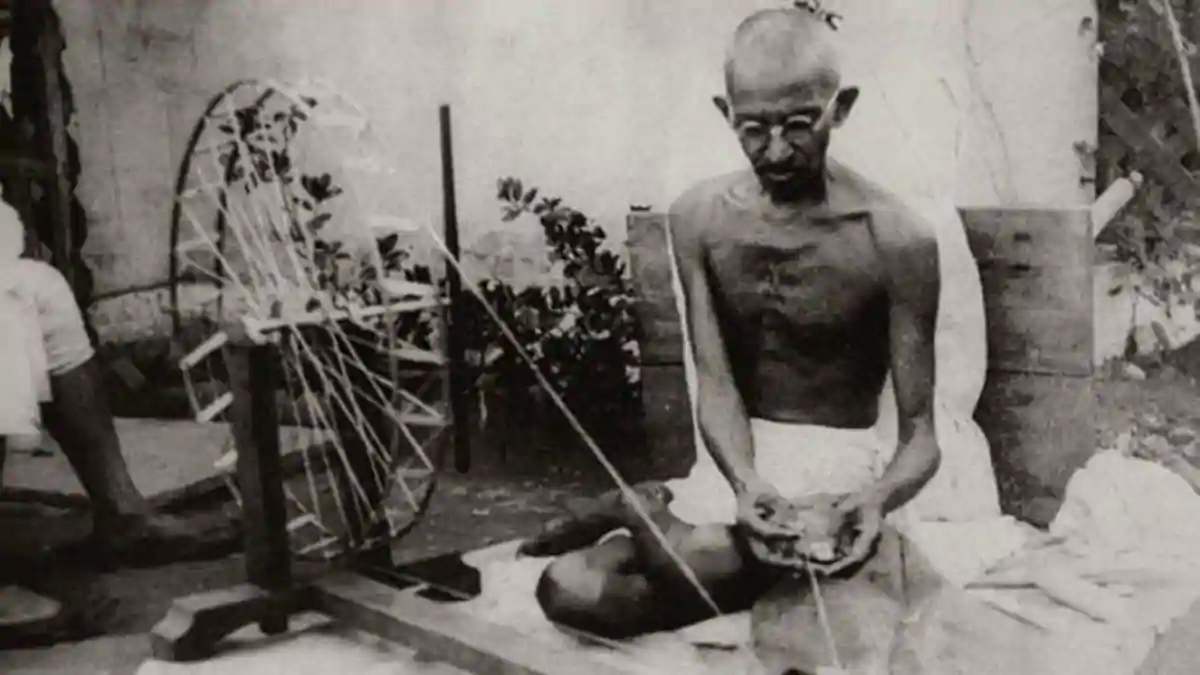

October 2 is famously known as the birthdate of Shri. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi or Mahatma Gandhi, who is indisputably the most important freedom fighter in the Indian Independence struggle against British Colonial Rule and widely recognised as the ‘father of the nation’ by Indians. An ardent follower of the philosophies of non-violence and truth, Gandhi has been instrumental in the independence of not only India, but also South Africa and has impacted similar movements throughout the world. Not only had he inspired countless nationalist leaders in India (including former Prime Minister of India, Shri. Lal Bahadur Shastri, who shares his birth anniversary with Gandhi), Gandhi’s life, struggles, and contributions had inspired innumerable individuals throughout the world. Even today, his life, teachings and legacies continue to inspire billions in many ways.

This year, the world celebrates one-hundred and fifty second (152nd) birth anniversary of Gandhi. As is well-known, Gandhi had worked in multiple capacities throughout his life such as being a writer, politician, lawyer, editor, columnist, and a journalist. He has also adorned the robes of both being a follower and leader of noble ideals such as non-violence, truth, Hinduism, Indic ideals, feminism, secularism, justice, self-reliance (Atmanirbharta), welfare, substantive equality (including gender and caste equality), anti-colonial ideals, and various forms of abolitionism. In this article, we shall discuss some of Gandhi’s views on law and legal matters through his life, as well as his tryst with the legal profession.

GANDHI AS A LAWYER

In the year 1887, Gandhi had cleared his matriculation examination. Upon suggestions from a family-friend, Gandhi and his family had decided that he should be sent to England to pursue legal studies. Shri. O.P. Motiwal (1970) states that Gandhi’s first reaction was that he should not pursue studies abroad owing to his poor knowledge of English and self-perceived difficulties in learning Latin (which was required to understand the law books and legal jargon). Nevertheless, he later built up his mind to take up all challenges and pursue law abroad.

On June 10, 1891, Gandhi was called to the Bar and shortly enrolled as a Barrister in the High Courts, after passing his law examination. Gandhi was noted to remark that, “It was easy to be called, but it was difficult to practice at the Bar. I had read the laws, but not learnt how to practice law.” This is a statement that indisputably every practicing Advocate across generations will relate to, since years of legal studies at even the best law schools in India and foreign countries do not ultimately prepare law students for legal practice and its challenges, in spite of claiming to do so. Initially, Gandhi started his practice at Bombay which lasted for six months. He found it difficult to practice Indian law, since his studies in England had taught him only Roman Law and Common Law, whilst he required knowledge of various Indian statutes and especially procedural laws – a difficult task which he had to do from scratch. In spite of his hard work, he was earning a meagre income and did not succeed in many cases at Bombay. Consequently, he moved to Rajkot, where he managed to earn a stable income for a while.

Eventually, he decided to look for better places to practice and he accepted an offer from M/s. Dada Abdulla & Co., South Africa, to work for its litigations. During his journeys, he interacted with various individuals and leading Barristers. Motiwal (1970) states that Gandhi once remarked: “Facts mean truth, and once we [lawyers] adhere to truth, the law comes to our aid naturally”, while reflecting on his experiences as a lawyer in South Africa after returning to India. In South Africa, while successfully practicing litigation, he also learned the benefits of ‘out-of-court settlements’, which led him to note that: “I had learnt the true practice of law. I had learnt to find out the better side of human nature and to enter men’s hearts. I realised that the true function of a lawyer was to unite parties driven as under.” In time, Gandhi would, inter alia, become deeply involved in South Africa’s struggles against the British Rule and its racism against African populations, as well as go on to become the most important leader of the Indian Struggle for Independence. However, there is no shadow of a doubt that Gandhi had already emerged as a well-established, immensely successful, and multi-skilled lawyer.

GANDHI ON TRUTH, THE LEGAL SYSTEM, AND THE NEED FOR ‘INDIANISATION’ OF JUSTICE SYSTEM

Gandhi was an ardent follower of the principle of ‘truth’ and possessed the reputation of being amongst the most honest lawyers. His philosophy of truth impacted his legal practice and conduct. He had vowed to never take up a false case or tutor hired witnesses. He also made sure to let full facts come forward and make any errors be well-known to courts and all parties in the litigation. Thus, he always followed his conviction in the value of ‘truth’ and later noted that: “It was not impossible to practice law without compromising truth.” However, he also added a cautionary note by stating that: “Even truthfulness in the practice of the profession cannot cure it of the fundamental defect that vitiates it.” His immense reputation was recently reflected upon by a Full-Bench of the Supreme Court headed by the previous CJI, Hon’ble Mr. Justice Sharad Arvind Bobde, when the bench dismissed a writ petition seeking a direction to the government to award the most prestigious Bharat Ratna award to Mahatma Gandhi. CJI Bobde exclaimed that: “He [Gandhi] is much higher than the Bharat Ratna. He is held in much greater esteem by the people… what is the Bharat Ratna for Mahatma Gandhi”, which rightly demonstrates the sentiment that Bharat Ratna shall never be sufficient to recognise the great contributions of Gandhi to India and the world.

Indian Courts have often referred to or relied on Gandhi while dictating their judgments or orders, showing that even after death, his impact on the legal community continues to grow ever stronger. If one searches “Gandhi OR Mahatma Gandhi” (using Boolean expression ‘OR’ to ensure that the judgments do refer to ‘Mahatma Gandhi’) on the Manupatra legal database (as on September 30, 2021), they shall find 307 references to Mahatma Gandhi in Supreme Court Judgments and Orders, with an upward trend in top-court’s invocations of Gandhi during the 21st century. One of the famous invocations of Gandhi was in the suo-motu contempt matter against self-proclaimed public interest lawyer, Prashant Bhushan by the Supreme Court, where Bhushan and the Full Bench had both referred to Gandhi during the hearings and the final judgment (mentioning Bhushan’s invocation of Gandhi) [Citation: Prashant Bhushan and Another, In Re, (2021) 3 SCC 160]. There are also over hundred legislative acts/statutes/bills/ordinances/policy documents which have referred to Gandhi ever since Indian independence in 1947 as per the SCC Online database.

American Law Professor and Gandhian Scholar, Prof. Charles R. DiSalvo (Book: Gandhi, Attorney at Law – The Man Before the Mahatma, 2013), had stated that while Gandhi “never lost faith in the law”, Gandhi had “eventually lost faith in the traditional legal system – courts, judges, lawyers, litigation.” As noted by Mr. Ashutosh Sharma (2019), Gandhi had “believed that Indian justice system rewarded the wealthy and compounded the miseries of the poor. Yet, he [Gandhi] would enjoin lawyers to place “truth and service” above the perks of the profession. He advised lawyers to write their petitions in simple language.” Recently, Chief Justice of India, Hon’ble Mr. Justice N.V. Ramana had iterated a similar sentiment by saying that ‘Indianisation’ of the country’s legal system was necessary. CJI Ramana elucidated his sentiment by stating that: “The common man should not be apprehensive about approaching the courts and authorities… When I say Indianisation, I mean the need to adapt to the practical realities of our society and localise our justice delivery systems.” CJI Ramana also advocated increasing use of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms including mediation, in line with Gandhian thinking, as a step towards Indianisation of the country’s legal system. Moreover, he also batted for greater use of regional languages in court proceedings and entire litigation process to make the legal system litigant-friendly – a stance Gandhi would have supported both from his personal experiences from his practice and due to the need for decolonialisation. CJI Ramana’s statements explicitly support the Gandhian position that the Indian legal system still regrettably suffers from being a colonial creation and continually perpetrates an anti-litigant culture, as well as requires greater introspection. In 2014, DiSalvo further noted that: “Gandhi found in the law a way it could be used against itself to create social change – change even in the law itself. That way was disobedience.” Consequently, the law in view of Gandhian thinking, law itself if properly used, can be an instrument to Indianise the legal system. Former USA President Donald J. Trump had recently signed the ‘Gandhi-King Scholarly Exchange Initiative’, an educational forum between USA and India to study the work and legacies of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., which presents an opportunity for production of scholarship and research into a Gandhian solution to reforming modern legal systems in India and USA.

GANDHI, DECOLONIALISATION AND CONSTITUTION

Gandhi was obviously a staunch critic of colonialism, Western ‘civilization’ and modernity. He was a decolonial theorist beyond par, and also wielded his praxis while displaying ‘decoloniality in action’. Gandhi’s quest for decolonisation of the Indian mind blended well with the skills he had learnt as a lawyer, i.e., negotiating, mediating and drafting. Having been a student of the Anglo-Saxon legal system himself, he could produce a powerful critique of the fundamental tenets of the system, and also comprehended the enormity of problems they posed in the Indian context. His critical examination of lawyering as a profession in his civilizational manifesto Hind Swaraj was a testimony to this deep understanding. Not only did he realise that the nature of the adversarial system of litigation pitted individuals against each other with little scope for reconciliation, but also saw through it that such a profession was bound to exacerbate conflicts as it helped provide a steady source of income for those practicing law. In this way, the system itself was based on, and promoted immorality and disintegration of harmony within a given society. Importantly, Gandhi also grasped the deleterious implications of too much emphasis on a rights-based discourse for any society, and thus advocated an equal, if not greater, emphasis on the duties of individuals as a responsible citizenry. Once while responding to English author H.G. Wells on a draft bill of rights, Gandhi suggested he draft a “cosmopolitan charter of duties instead – a statement of what citizens of the world owe to each other”. On the foregoing note to Wells, he further stated that: “Begin with a charter of Duties of Man and I promise the rights will follow as spring follows winter. I write from experience. As a young man, I began life by seeking to assert my rights and I soon discovered I had none – not even over my wife. So I began by discovering and performing my duty to my wife, my children, my friends, companions and society and I find today that I have greater rights perhaps than any living man I know. If this is too tall a claim, then I say I do not know anyone who possesses greater rights than I.”

Being a passionate draftsman and a votary of decolonialisation and indigeneity, Gandhi did have his own grand scheme of what an Indian Constitution post-Independence should look like. This vision of Gandhi has been best captured by Shriman Narayan Agrawal’s book titled The Gandhian Constitution for Free India. Village panchayats as self-sustainable democratic units were placed at the centre of his constitutional framework, aiming towards a decentralised mode of governance rather than its top-down imposition. As a matter of praxis, there was even a novel experiment in constitution making undertaken by the princely state of Aundh, post which the final draft did get the approval of Gandhi and was smoothly functional for a period of around nine years governing the polity of Aundh (Chapalgaonker, 2016). Recently, there has been a spurt in Bharat-centric decolonial scholarship, with a “significant intervention” (as one of our professors put it) being made by the Supreme Court lawyer, Advocate J. Sai Deepak with his book ‘India that is Bharat’, which signifies a paradigmatic shift towards scrutinising the Indian Constitution threadbare for the presence of “colonial consciousness”, and explicitly adopts a decolonial approach to this fundamental document of our polity. Moreover, Hon’ble Mr. Justice P.S. Narasimha, a little while back, while referring to the remarks of CJI Ramana about ‘colonial entrenchment’ within Indian judicial system, noted that, “Decolonialisation is actually a constitutional mission for us.” In such a backdrop, Gandhi as a decolonial constitutional theorist and drafter, and his actions towards envisioning an indigenous, and not just an autochthonous, constitution gain more significance than ever. As one of us has previously stated (Yashowardhan Tiwari, 2021): “Gandhi’s Constructive Programme was also a part of his constitutional idea of surajya. Gandhian vision of the constitution was a quest for swaraj, a manifesto against all-pervasive government regulation, demand for freedom, and his civilisational ideal of the Ramarajya.”

GANDHI’S COMMITMENT TOWARDS WOMEN EMPOWERMENT AND GENDER EQUALITY

Amongst all the views attributed to the Mahatma, his opinions regarding the role and social status of women are arguably the most misunderstood and a subject of regular criticism. While academicians continue to debate this controversial aspect of Gandhian philosophy, there are certain undeniable facts on record that continue to highlight and give sufficient proof of the Mahatma’s commitment towards the emancipation of women. As we celebrate the occasion of Gandhi’s birth anniversary, it may be prudent to briefly revisit and ponder upon some of his opinions on women empowerment.

The Mahatma strongly advocated for, and truly believed, that men alone would not be able to lay the foundations of Swaraj in India (Anima Bose, Women in Gandhi’s India, India International Centre Quarterly, October 1975). If the newly independent country was to become Atmanirbhar (self-sufficient) in the truest sense of the term, and tread upon the path of decolonialisation, it would have to be a ‘nationalist revolution’ in both the personal and political spheres of life. (G.A. Natesan, Speeches and Writings of M.K. Gandhi, 1922). To achieve reformation in the ‘personal’ sphere, Gandhi realised that Indian women had to be mobilised in order to ensure their active participation in India’s Freedom Struggle. This shows how Gandhian philosophy envisioned a more inclusive and participative form of aspirational democracy.

One also finds adequate evidence of Gandhi’s commitment towards women empowerment in his columns published in the Harijan where he applauds women for demonstrating outstanding character of resilience during the freedom struggle – “It may be that there shall arise one among them who will be able to go much further than I can ever hope to do. For, woman is more fitted than man to make explorations and take bolder action in ahimsa” (Harijan, November 5, 1938). The genuineness of his commitment is equally corroborated in his political strategies during important protest movements like the Salt Satyagraha-Dandi March. The famous freedom activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay recorded in her book Indian Women’s Battle for Freedom “So far as women were concerned, it (Salt Satyagraha) was ideally tailor made for them……as women presided over culinary operations, salt is for them the most intimate”. The Mahatma was aware of this and he strategized the entire movement to include participation of India women. This further shows the Mahatma’s relentless advocacy for a gender inclusive form of societal existence.

It may be very important for us to revisit the Mahatma’s staunch criticism to the social evil of Child Marriage and Dowry. He had famously said that: “It is irreligion, not religion, to give religious sanction to a brutal custom.” As Madhu Kishwar (1985) notes, he dismissed the religious texts which sanctified such an immoral practice which would bring disastrous consequences for the social fabric of the nation. The Mahatma is noted to have remarked that it is better if girls remained unmarried their entire life rather than being dishonoured and humiliated by marrying into families that demanded dowry. It is also pertinent to mention that Gandhi batted for widow remarriage and stated that women must have the same freedom to remarry ‘without incurring any odium’ as men had. On widow remarriage, Gandhi added that even a grown-up widow or elderly widow who “cannot restrain herself should have the right to remarry without consequences.” Gandhi’s advocacy for the emancipation of women and ensuring a more gender inclusive Indian society was unequivocal in its demand. His words of advice ring loud even today: “If nonviolence is the law of our being, the future is with women.”

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Mahatma Gandhi’s originality as a thinker lies in his radical critique and equally radical solutions to law from both an insider’s as well as an outsider’s perspective. We as students and practitioners of law, must learn from him the art of retaining and deploying lawyering skills throughout his life despite major disillusionments regarding its moral basis. Reading Gandhi carefully becomes an imperative when working towards the decolonialisation and Indianisation of our legal and justice systems, or working for the eradication of gender and caste discrimination. Questions about his seeming absence from our constitution inevitably arise, and searching for their answers helps discover innovative ways to root out the colonial hangover within the Indian Constitution.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We dedicate this article to Prof. (Dr.) Ravi K. Mishra (Deputy Director, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library). His teachings and lectures inspired us to learn, research, and write about Mahatma Gandhi, as well as Gandhi’s life, ideas, practice, and debates.