Over the electronic screen, Azaad addresses his audience directly, exclaiming, “Tum Azaad ho, tum Azad ho,” while pointing his index finger at various members. I’m referring to the climax of “Main Azaad Hoon” (1989). Since the 1940s, when historical themes made way for social issues in Hindi cinema, numerous movies have depicted the plight of the common man. Whether it’s the farmer cheated into a debt trap by the zamindar in “Do Bigha Zamin” (1952) or the young Arjun (1985) being used as a pawn by corrupt politicians, these films delve into the challenges faced by ordinary people. Parallel cinema, committed to realism, explores these problems deeply, acknowledging that there are no easy solutions. In contrast, commercial cinema, with its penchant for make-believe, often offers quick fixes in the form of vigilantes who dispense justice with superhero-like might.

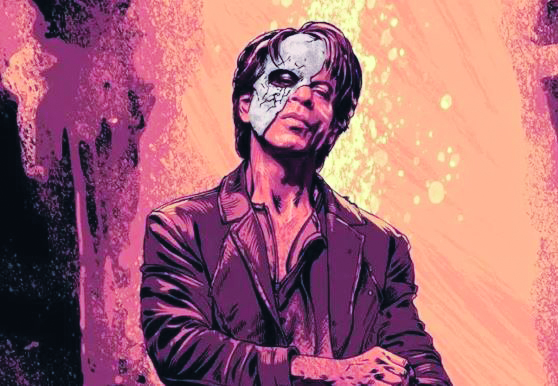

The backstory of Azad (Shah Rukh Khan) in “Jawan” bears resemblance to characters like Vijay Verma in “Deewar” (1975). He grows up to become a policeman but, much like in “Shahenshah” (1988), assumes an alternate identity to combat criminals in ways his uniform wouldn’t allow. If you’ve seen David in “Aakhree Rasta” (1986) seeking personal revenge, or the nameless vigilantes in “A Wednesday” (2007) and “Main Azaad Hoon” (1989) who hold a city hostage to cleanse it of corruption, then you’ll recognize the storyline of “Jawan.”

Naturally, a vigilante needs to possess a certain superhero-like quality to tackle a broken system, so a reasonable suspension of disbelief in commercial mainstream cinema is acceptable. However, “Jawan” loses itself in a virtual world of implausible scenarios. Its logic goes haywire, akin to someone who has just consumed a kilogram of raw chilies. Vikram Rathore, struck by five point-blank bullets (yes, five), plummets from an estimated 7,000 feet off an airplane, lands in a body of water, and collides with a rock—only to return as a seemingly invincible figure, resembling “The Phantom” (although Lee Falk’s name isn’t even mentioned in the credits). Then, there are the 6,000 women prison inmates, clad in spotless white jerseys, trousers, and light green jackets, appearing more like advocates for eco-friendly energy sources. Their flawless faces, expertly threaded eyebrows, and precise eyeliners make jail look surprisingly enticing. How did nine lakh Electronic Voting Machines end up in that prison? Furthermore, Deepika’s character remained unaware of her pregnancy until a prison doctor confirmed it through a pulse check—yes, just by feeling her pulse. And whose child was she carrying, considering her husband Rathore had gone missing, and murder trials typically take at least a year to conclude? These logical inconsistencies would even have made Manmohan Desai blush.

Cinematic absurdities are not uncommon in the world of film. Examples such as “Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro” (1983), “Kaminey” (2009), “Delhi Belly” (2011), “Is Raat ki Subah Nahin” (1996), and “Urf Professor” (unreleased) come to mind. These were crime flicks as well, structured like slapstick chase comedies with a cartoony pastiche feel, elevated by quirky action, characterization, dialogues, and situations. The comedy in these films extended beyond just quirky actions and dialogue; it was woven into the very fabric of the films through lighting, camera angles, editing, and cutting.

However, “Jawan” attempts to pass off its nonsensical narrative as absolute truth merely because the Bollywood superstar was delivering it. This is where the film comes across as insincere. It underestimates the sensibilities of the educated and discerning audience. The much-praised ‘voice-against-a-rotten-system’ climactic monologue by Khan felt like someone suddenly remembering, at the tail end of a booze-filled corporate party, that they had forgotten to address the meeting’s most crucial agenda item.

Indeed, “Jawan” serves as a fascinating case study in marketing. First, the “north-south-ki-mit-gayi-dekho doori-hi-saari” strategy, featuring Vijay Sethupathi, Nayanthara, and Priyamani, allowed SRK/Atlee to cast a wide net. Even though Vijay and Priyamani were somewhat underutilized, their names in the credits appeared to be the key factor. Secondly, substandard music was cleverly packaged into visually stunning videos, attracting a considerable number of eyeballs. Third, “Jawan” shines with technical brilliance. In fact, the gadgetry in SRK’s superbike could have inspired Q in James Bond films to come up with new ideas. The technical superiority of “Jawan” was a given, as vintage wine is best served in new designer bottles.

Don’t worry Red Chilies, the sheer size of the market and your marketing muscle will make your INR 1000 crores for you because the shallower aspects of Jawan cater to the targeted ‘niche’ 90%. You have done it! Who cares for the ‘mass’ 10%?

Balaji Vittal is a National Award and MAMI Award-winning author of Bollywood books, columnist, commentator, and public speaker.