In a major constitutional clarification, the Supreme Court ruled that the President and Governors cannot be forced to follow judicially fixed timelines while approving Bills. The Court said their actions are not justiciable unless a Bill becomes law. The ruling marks a clear boundary between the Judiciary and the Executive.

Top Court Answers President Murmu’s Questions

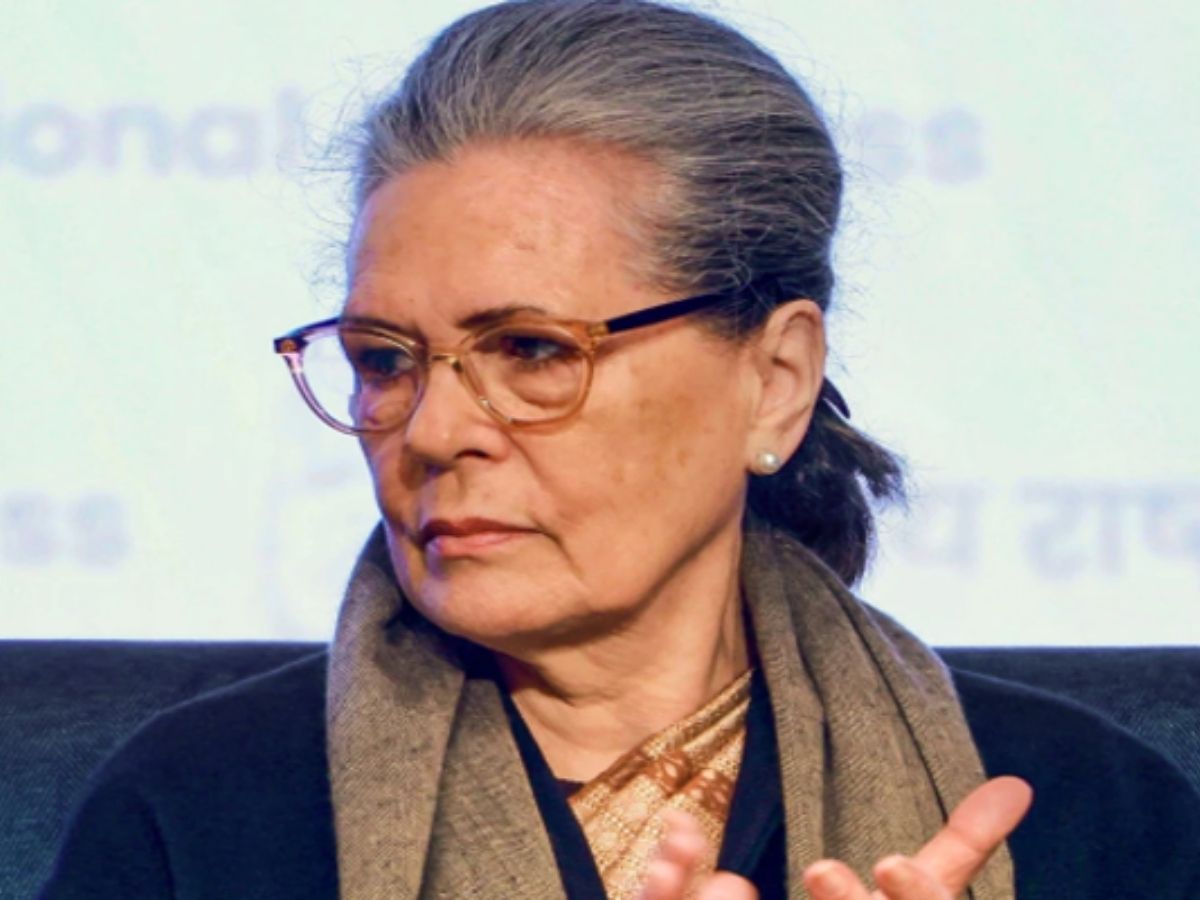

The decision came in response to questions raised by President Droupadi Murmu under Article 143. She sought clarity after a two-judge bench, in the Tamil Nadu case, appeared to set deadlines for the approval of Bills.

The President asked the Court, “In the absence of a constitutionally prescribed time limit, and the manner of exercise of powers by the Governor, can timelines be imposed and the manner of exercise be prescribed through judicial orders for the exercise of all powers under Article 200 of the Constitution of India by the Governor?”

She also questioned whether her own discretion under Article 201 was justiciable. She further asked, “Is the Governor bound by the aid and advice tendered by the Council of Ministers while exercising all the options available to him when a Bill is presented before him under Article 200 of the Constitution of India?”

Timelines Are ‘Strictly Contrary’ to Constitution

A five-judge Constitution Bench led by Chief Justice BR Gavai held that imposing timelines on the President or Governors is unconstitutional. The bench stated that the Constitution gives these offices “elasticity” to act based on complex federal and democratic considerations.

It also rejected the previous idea of “deemed assent”. The Court said, “deemed consent of the Governor, or President, under Article 200 or 201 at the expiry of a judicially set timeline, is virtually a takeover, and substitution, of the executive functions by the Judiciary, through judicial pronouncement, which is impermissible within the contours of our written Constitution”.

New Timeline of the Governor

In a recent clarification, the Supreme Court stated that Governors cannot be forced to follow a fixed, court-mandated timeline for clearing Bills. However, the Court also made it clear that Governors cannot indefinitely delay decisions.

If there is an unusually long or unexplained delay, courts may intervene to examine whether constitutional duties are being fulfilled. The ruling aims to maintain the Governor’s discretionary space while preventing misuse through prolonged inaction.

What Changes After the New Timeline?

It cannot impose fixed deadlines (like 2 weeks or 30 days) on Governors. But Governors also do not have unlimited time — they must act “within a reasonable period.”

If a Governor sits on a Bill for too long, courts can review the delay. The aim is to ensure the Governor is not misusing silence or delay to influence political outcomes.

So, in short, there is no rigid timeline, but no endless delay either.

Tamil Nadu Case and the Trigger

In April, a two-judge bench invoked Article 142 to declare ten Bills in Tamil Nadu as “deemed to have been assented” after the Governor withheld them. The judgment had criticised delays and urged constitutional discipline. Some political leaders described it as judicial overreach.

President Seeks Clarity Amid Governance Concerns

President Murmu asked whether judicial timelines and review could apply to the President’s or Governors’ discretion, especially when Bills raise constitutional questions. Her letter reflected growing debate on how long Governors can hold Bills and whether courts can intervene.

Court Allows Only Limited Scrutiny of Prolonged Inaction

While the Bench barred courts from examining the merits of the President’s or Governor’s actions, it allowed scrutiny of extreme delays. It said, “Inaction that is prolonged, unexplained and indefinite, will certainly invite limited judicial scrutiny.”

The Court added that no constitutional authority works in isolation. It said all organs function like interconnected “cogs” that keep the system moving.

Reset in Centre–State Power Balance

This ruling marks a shift in Centre–State dynamics. While it protects the executive authority of Governors and the President, it also warns them against indefinite delays. The decision may reshape how states push legislation and how the Union government interprets gubernatorial roles in politically sensitive states.

It sets a new framework: no judicial deadlines, no “deemed assent,” but no unchecked stagnation either.