The emergence of BJP as a potent political force, particularly after 2014, has not weakened secularism as a political ideal. A majority of Indians strongly adhere to religious harmony and ‘sarv dharm sambhav’ as an expression of secularism. This explains why Indian Muslims still find secularism as an important metaphor for asserting their rights and dignity.

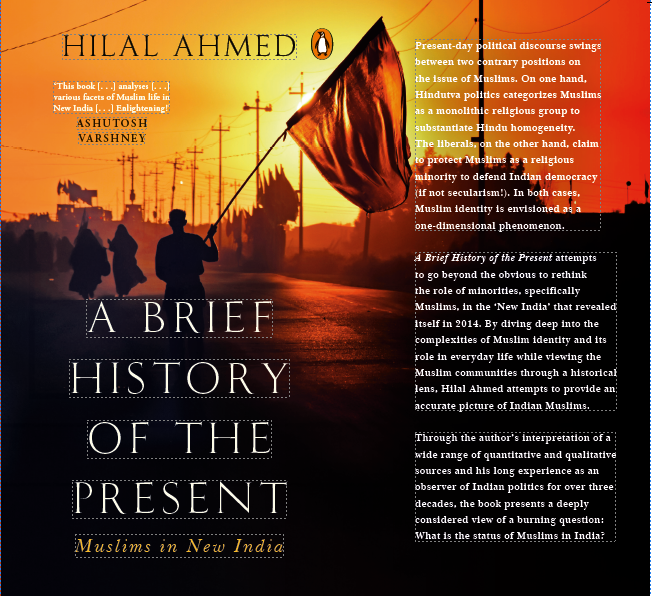

Author-scholar Hilal Ahmed, in his well-researched and thought-provoking book, ‘A brief History of the Present -Muslims in New India’ [Penguin Random House] argues cogently how social justice, federalism, secularism, Constitution, parliamentary form of government continues to be the core principles of Indian politics. “These ideals are formed and practised outside the institutional realm of the Parliament and judiciary. This is perhaps the most fundamental truth of our contemporary political life, which needs to be acknowledged seriously if we go beyond the given Hindu Muslim divide,” concludes the author who is a leading commentator on political Islam and Indian democracy. Ahmed’s earlier pioneering works include ‘Muslim Political Discourse in Postcolonial India- Monuments, Memory, Contestation,’ Siyasi Muslims: A story of Political Islam in India,’ Democratic Accommodations: Minorities in Contemporary India’ and ‘Allah Naam ki Siyasat.’

However, according to Ahmed, the meaning of religion and religiosity have changed considerably in the last decade. The fascination of displaying religiosity publicly has two important implications. The perception of religion as a spiritual -moral force is disappearing whereas religion as an expression of identity is gaining ground. Religion is thus seen as ‘competing ideologies’ while religiosity is treated as an end in itself. Ahmed laments over absence of substantive discussions on moral religious values or inter faith dialogue.

The public display of religiosity is evident from shobha yatras, maha panchayats and kanwarya yatras by the state that seeks to emphasise that religion can only be meaningfully observed if it is celebrated in public. The competitive dimension of religiosity can be seen by green minarets of mosques, public display of namaz on roads, loudspeaker recitation of azaan five times a day and visibility of Muslim figures in skull cap or hijab. Here Hilal Ahmed makes a telling observation: “the public presence of Islam is used as a resource to create a fear psychosis…. the failure of the political class is evident. They do not have the moral courage to question the emerging dogmatic nature of religion. They fear that such a moral intervention may disturb their electoral equation. This is perhaps one of the most serious challenges for our democratic sensibilities.”

In the last scene of the iconic Garam Hawa, [1973] protagonist Salim Mirza and his son Sikander are shown leaving Agra and India for good. As the Tonga approaches Agra Cantt station, the father-son duo, facing social ostracization — shift in people attitudes, unable to secure bank loans and losing their means of survival, encounter a massive protest rally which seeks jobs and opportunities. First Sikander, and then Salim, join the flag-waving mob asking for a better deal for the dispossessed. The train to Attari is forgotten, and the final scene brings a sense of hope as we see Salim accept his situation in a new way and begin to take charge of his life.

Hilal leans on this final scene of M S Saathyu’s Garam Hawa to say how anti-Muslimism can not be separated from the wider struggle for social justice and economic equality. The author is spot on in saying, “the answer lies in a radically revised template of progressive politics – one which allows the individual like me to critique economic injustice and social inequalities while adhering to my conception of a liberative Islam.”