NEW DELHI: In global rankings, power has long been measured through economic size, military strength, technological capacity, and geopolitical reach. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), per capita income, export volumes, defence spending, and innovation indices have dominated how nations are compared and judged.

Yet as the world confronts overlapping crises—climate instability, widening inequality, democratic backsliding, armed conflict, mass displacement, and technological disruption—a fundamental question is being asked with increasing urgency: Are powerful nations also responsible nations?

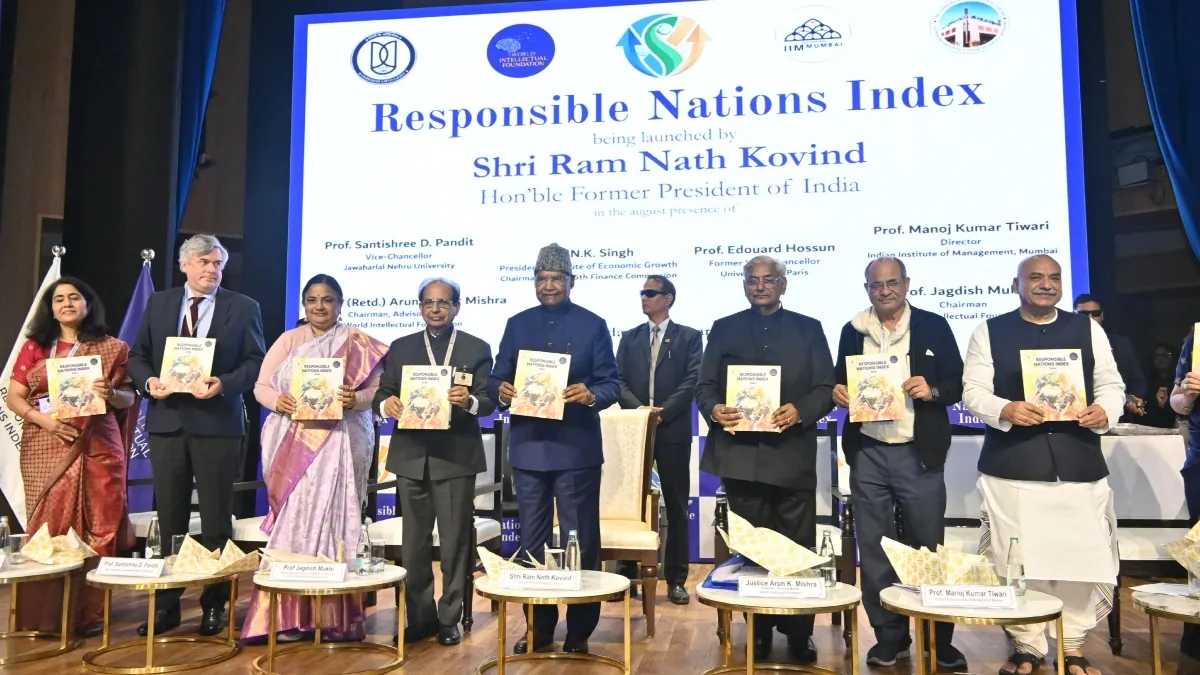

The Responsible Nations Index (RNI) 2026 emerges from this question. Developed by the World Intellectual Foundation, in collaboration with Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and Indian Institute of Management (IIM) Mumbai, the index proposes a reframing of how national success should be evaluated. Rather than focusing solely on what nations possess, it asks how nations exercise their power—towards their citizens, towards the environment, and towards the global community.

Covering 154 countries, the RNI draws upon internationally standardised data from sources such as the World Bank, United Nations agencies, IMF, WHO, FAO, ILO, World Justice Project, Our World in Data, and other globally recognised datasets. Its findings challenge conventional hierarchies of global power and complicate the assumption that economic strength naturally translates into ethical governance or global responsibility.

The results are revealing. Singapore ranks first, followed closely by Switzerland, Denmark, Cyprus, and Sweden. India places 16th, outperforming several advanced economies. The United States ranks 66th, well below many middle-income and developing nations. These outcomes are not incidental; they reflect a deeper reordering of how responsibility is measured and understood.

WHAT IS THE RESPONSIBLE NATIONS INDEX?

The Responsible Nations Index is not a power index. Nor is it a happiness index, a democracy index, or a development index—though it intersects with elements of all of them. Instead, it evaluates nations through the lens of responsibility, defined as a country’s commitment to using its power in ways that promote collective well-being rather than narrow self-interest.

At its core, the RNI is built on the premise that sovereignty is not only a right, but also a responsibility. In an interconnected world, national decisions on emissions, trade, war, technology, migration, or governance—rarely remain confined within borders. The index therefore assesses how responsibly nations act in three interconnected domains.

The RNI operationalises responsibility through three pillars, further broken down into seven dimensions, captured through 58 indicators.

The Three Pillars and Seven Dimensions

The RNI operationalises responsibility through three pillars, further broken down into seven dimensions, captured through 58 indicators.

- INTERNAL RESPONSIBILITY: This pillar measures how states treat their own citizens. It focuses on whether development is inclusive, governance is accountable, and dignity is protected. It includes three dimensions: Quality of Life, Governance, and Social Justice and Empowerment. Indicators include access to healthcare and education, life expectancy, gender equality, income inequality, rule of law, judicial independence, civil liberties, and political participation.

- ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSIBILITY: This pillar assesses how nations manage ecological resources and environmental externalities. It includes Environmental Protection. Indicators cover carbon emissions, energy use, renewable energy share, deforestation, biodiversity pressures, water stress, and environmental sustainability policies.

- EXTERNAL RESPONSIBILITY: This pillar evaluates how nations behave beyond their borders. It includes Commitment to Peace and International Economic Relations. This captures military engagement, arms exports, conflict involvement, peacekeeping contributions, aid, trade fairness, and economic cooperation.

Together, these dimensions aim to measure not just outcomes, but conduct.

Methodology: How the Rankings Are Calculated

To ensure comparability, all 58 indicators are normalised on a 0–1 scale using min-max scaling. Indicators are aligned directionally so that higher scores always represent more responsible outcomes.

An equal weighting approach is used across indicators, dimensions, and pillars. This reflects a normative choice: responsibility in one domain cannot morally compensate for irresponsibility in another. Environmental stewardship does not excuse democratic erosion; economic performance does not offset militarism.

The final RNI score is calculated using the geometric mean of the three pillars, preventing any single pillar from dominating the overall score. Countries are then ranked and grouped into responsibility tiers ranging from Very High to Very Low. The methodology has undergone independent academic validation, ensuring statistical robustness, internal consistency, and interpretive clarity.

WHY POWER ALONE NO LONGER EXPLAINS GLOBAL STANDING

One of the central findings of the RNI is that economic power and responsibility do not move in tandem. Several high-GDP countries perform poorly on environmental ethics, social justice, or peaceful international conduct. Conversely, many developing and middle-income countries score comparatively well on responsibility metrics despite limited material power.

This divergence exposes what the report describes as an “evaluative paradox”: nations celebrated for development and influence may simultaneously undermine global welfare through environmental degradation, conflict, or institutional erosion.

The index highlights how global disparities are deepening, particularly in climate responsibility, judicial independence, and peaceful engagement—areas where the consequences of state action are increasingly transnational.

SINGAPORE AND SWEDEN: WHY THEY RANK AT THE TOP

Singapore, ranked first, exemplifies a high-performing responsible state within the RNI framework. Its strong governance institutions, low corruption levels, efficient public service delivery, economic resilience, and relatively controlled environmental footprint contribute to its top ranking. While often associated with strict governance, Singapore scores well on institutional accountability and policy coherence.

Sweden, ranked fifth, represents a different model of responsibility—one rooted in social democracy, strong welfare systems, gender equity, environmental leadership, and international peace engagement. Sweden’s sustained investments in renewable energy, social protection, and multilateral cooperation strengthen its external and environmental responsibility scores.

What unites top-ranking countries is institutional consistency, policy predictability, and a demonstrated willingness to balance national interest with global obligations.

INDIA AT 16: A COMPLEX RESPONSIBILITY PROFILE

India’s 16th rank places it among the higher-performing countries globally, ahead of several advanced economies including France, Japan, Canada, Australia, and the United States. India’s performance reflects strengths and constraints shaped by scale, diversity, and development stage.

The index recognises India’s progress in social inclusion, democratic participation, digital public infrastructure, and poverty reduction, alongside improvements in renewable energy adoption and climate commitments. At the same time, India’s challenges—environmental stress, inequality, judicial backlogs, and regional security pressures—are also reflected in the scores.

The RNI does not present India as an unqualified success story, but as a country navigating responsibility amid structural constraints inherited from colonial extraction and post-independence development pressures. Notably, the index explicitly acknowledges historical asymmetries; countries like India are assessed within a framework that recognises colonial legacies and uneven starting points—without lowering standards, but by contextualising outcomes.

THE UNITED STATES AT 66: A CASE OF POWER WITHOUT BALANCE

Perhaps the most striking placement is that of the United States, ranked 66th. Despite being the world’s largest economy and a central global actor, the US scores lower due to weaknesses across multiple responsibility dimensions. These include high carbon emissions, extensive military engagement, arms exports, social inequality, and governance polarisation.

The index does not single out the US for criticism, but its ranking illustrates a broader pattern: global influence amplifies responsibility, and failure to meet that responsibility carries systemic consequences. In the RNI framework, responsibility is not measured by intent or rhetoric, but by outcomes and conduct.

CHINA AT 68: ECONOMIC POWER, RESPONSIBILITY DEFICIT

China’s 68th rank highlights the gap between power and responsibility. Despite strong economic and infrastructure performance, its score is pulled down by weaker governance, civil liberties, environmental stress, and external conduct. High carbon emissions and limited transparency affect its internal and environmental responsibility, while its expanding global influence has not consistently aligned with cooperative, peace-oriented engagement. The ranking reinforces the index’s core argument that economic scale alone does not define responsible nationhood.

COLONIAL LEGACIES AND MORAL OBLIGATION

A distinctive feature of the RNI is its explicit engagement with colonial history and imperial extraction. The report argues that modern global inequalities cannot be understood without acknowledging how centuries of colonisation reorganised wealth, power, and ecological systems.

Countries that accumulated wealth through coercion, slavery, resource extraction, and environmental degradation bear a heightened historical responsibility to advance justice, climate repair, and equitable cooperation today.

This does not translate into automatic penalties, but it frames responsibility as forward-looking accountability, not historical guilt.

RESPONSIBILITY AS AN ETHICAL FRAMEWORK

Philosophically, the RNI draws from multiple traditions, including Indian civilisational ethics—particularly the concept of Dharma, where governance is a moral duty. This resonates with Gandhian ethics, Kantian universalism, Ubuntu, and other global traditions that link power with moral restraint.

The index thus represents an epistemological shift—from asking “How strong is a nation?” to asking “How responsibly does it act?”

What the Rankings Ultimately Reveal

The Responsible Nations Index positions itself as a living framework open to refinement as data improves and global realities evolve. Its significance lies in what the rankings collectively reveal:

- Responsibility is multi-dimensional, not reducible to wealth or influence.

- Institutional quality matters as much as economic capacity.

- Environmental ethics are central to national credibility.

- Power exercised without restraint destabilises global systems.

- Development pathways that integrate equity and sustainability perform better over time

- In this sense, the RNI is less about competition and more about recalibration—a tool to realign global evaluation with planetary and human realities.

A dIfferent Measure of National Success

As climate thresholds approach, conflicts intensify, and social trust erodes, the question of responsibility is no longer abstract. The Responsible Nations Index argues that in the 21st century, national greatness must be judged not only by what countries achieve, but by how responsibly they achieve it.

In a world where actions reverberate across borders, responsibility is no longer optional. It is, increasingly, the measure by which nations will be remembered.