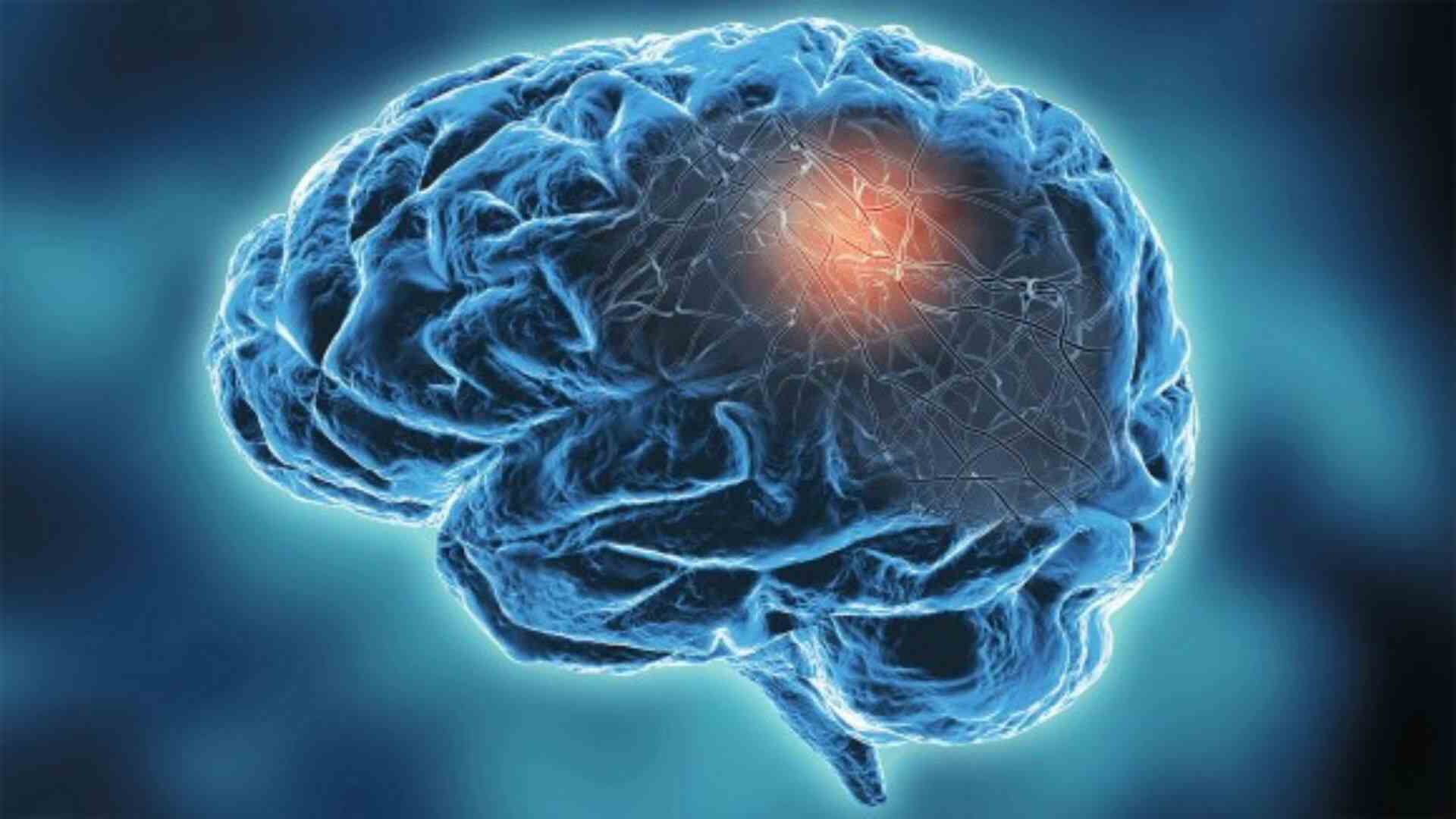

The causes of complex neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis remain a puzzle for scientists and doctors, making early diagnosis and effective treatment difficult. Even when identical twins share the same genetic risk factors, one may develop a neurological disorder while the other does not. This is because, unlike conditions such as cystic fibrosis or sickle-cell anemia, which are caused by a single gene, most neurological diseases are linked to many rare genetic variants. However, these variants alone do not determine who will develop the disease, as environmental factors and vascular risks like high blood pressure, aging, heart disease, and obesity also play significant roles.

One often-overlooked factor that connects many neurological diseases, according to Katerina Akassoglou, PhD, a senior investigator at Gladstone Institutes, is a toxic immune response triggered by blood leaking into the brain through damaged blood vessels. “Interactions between the brain, blood vessels, and the immune system are a common thread in the development and progression of many neurological diseases that have been traditionally viewed as very different conditions,” says Akassoglou, who is also the director of the Center for Neurovascular Brain Immunology at Gladstone and UC San Francisco. “Knowing that leaked blood is a key driver of brain inflammation, we can now approach these diseases from a different angle.”

Must Read: Study Reveals Biomarker Could Guide Liver Cancer Treatment Response To Immunotherapy

In a commentary published in Cell’s 50th anniversary “Focus on Neuroscience” issue, Akassoglou and her team outline their findings on how blood leakage into the brain can trigger neurological disorders. One protein, fibrin, normally involved in blood clotting, plays a major role in initiating a harmful chain reaction that damages neurons. This process has been observed in conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s to traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, premature birth, and even COVID-19. Akassoglou’s research shows that neutralizing fibrin’s toxic properties can halt this harmful process, offering protection against several neurological diseases in animal models.

“As a first step, we know that neutralizing fibrin reduces the burden posed by vascular dysfunction,” Akassoglou explains. Whether the blood leakage is caused by a head injury, autoimmunity, genetic mutations, brain amyloid, or infection, fibrin neutralization has shown to be protective in multiple animal disease models.

Her team developed a therapeutic monoclonal antibody that specifically targets fibrin’s inflammatory properties while leaving its role in coagulation intact. This fibrin-targeting therapy has shown promise in protecting against multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s, and COVID-19-related neurological effects in mice. A humanized version of this therapy is now in Phase 1 clinical trials through Therini Bio, a biotech company formed to advance Akassoglou’s discoveries.

In their commentary, Akassoglou and her colleagues argue that these seemingly unrelated neurological diseases should now be viewed through the lens of the blood-brain-immune connection. They foresee that future breakthroughs will come from collaborations among immunologists, neuroscientists, geneticists, bioengineers, drug developers, and others. “This is a new opportunity for drug discovery that goes beyond addressing genes alone or environmental factors alone,” Akassoglou says. “To usher in this new era, we must leverage new technologies and embrace an interdisciplinary approach that accounts for the important roles of immune and vascular systems in neurodegeneration.”

Also Read: IIT Study Reveals Shocking Truth: Tea In Paper Cups Is Poisonous