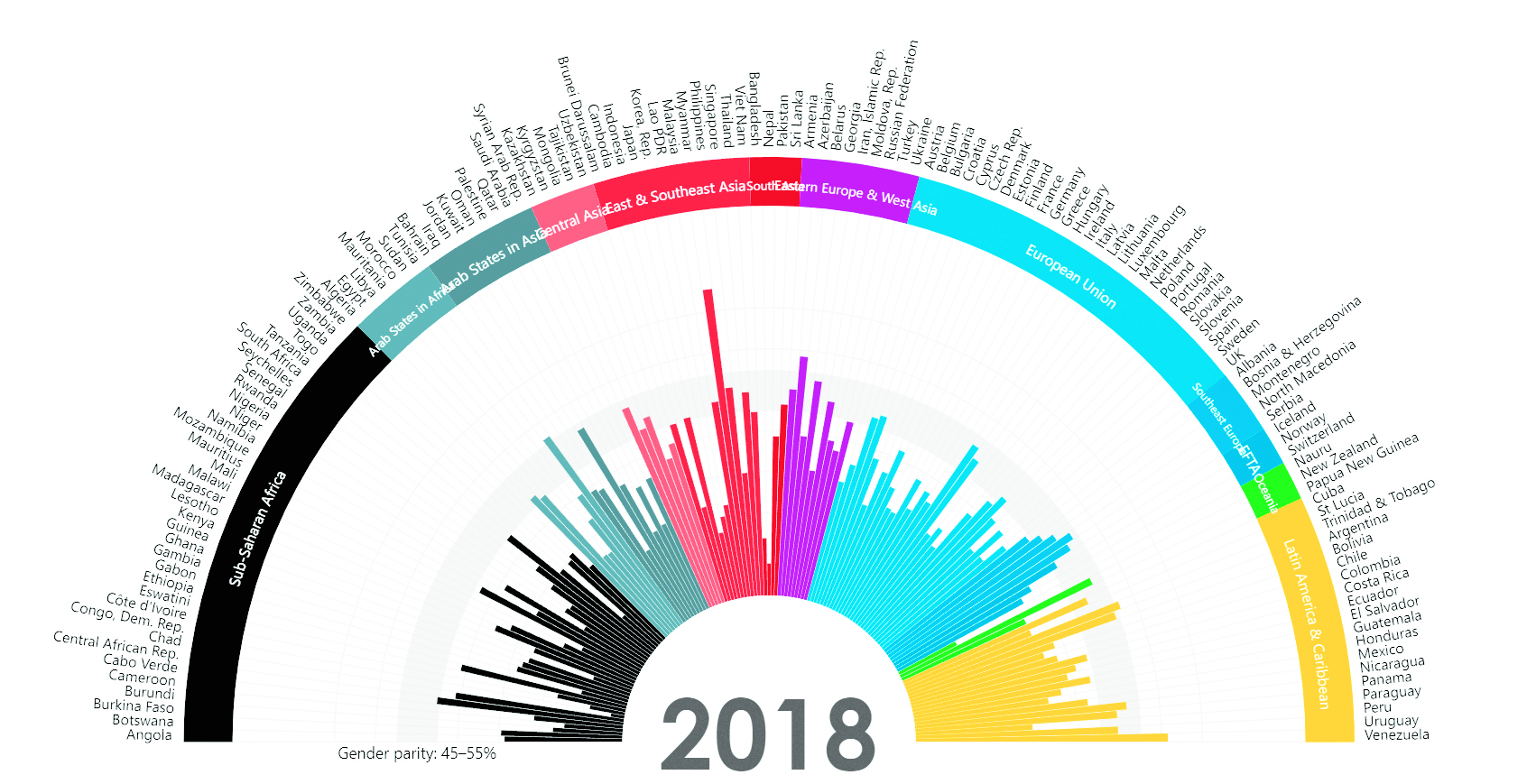

Globally, women constitute 33.3% of researchers based on headcounts, as reported by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics covering the years 2015–2018 across 107 countries.

These statistics are derived from a chapter in the UNESCO Science Report titled ‘To be smart, the digital revolution will need to be inclusive,’ which was released on February 11, 2021, in commemoration of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

Over the past two decades, an increasing number of countries are gathering and disclosing sex-disaggregated data on researchers. Despite this progress, significant data gaps persist.

Many countries in the Caribbean, Oceania, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa, including populous nations like Bangladesh, Brazil, India, and Nigeria, do not regularly collect sex-disaggregated data on researchers.

Moreover, UNESCO estimates exclude North America and China on account of the international incomparability of these data. The observed data gaps make it difficult to conclude most regions.

There is sufficient data, however, to confirm the trend observed in the previous UNESCO Science Report (2015) towards gender parity in Central Asia, Southeast Europe Latin America and the Caribbean.

Long way to go

In the Caribbean and certain regions of Asia and Africa, several countries boast a significant share of women researchers, showcasing progress in gender representation. Some notable examples include Venezuela (61%), Trinidad and Tobago (56%), Argentina (54%), North Macedonia and Kazakhstan (53%), Serbia (51%), Montenegro (50%), Cuba, Paraguay, and Uruguay (49%).

The enduringly high proportion of women researchers in numerous European and Asian nations can be traced back to the Soviet Union’s commitment to gender equality. This is evident in countries such as Azerbaijan (59%), Georgia and Kazakhstan (53%), Serbia (51%), and Armenia (50%).

South and Southeast Asia have seen growing achievements in gender parity, with countries like Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand reaching this milestone. Sri Lanka experienced a remarkable increase, with women comprising 46% of researchers in 2015, up from 24% in 2006.

In sub-Saharan Africa, South Africa has maintained gender parity, with women accounting for 45% of researchers since 2015. Although Mauritius initially achieved gender parity in 2015, it has since seen a slight decrease. Senegal stands out for significantly increasing the share of women in the research pool from 10% to 29% between 2006 and 2015.

Several Arab countries have made notable progress toward gender parity, including Algeria (35% in 2005 to 47% in 2017), Egypt (36% in 2007 to 46% in 2018), and Kuwait (23% in 2008 to 53% in 2018). Tunisia currently has a slight imbalance in favour of women in its research ecosystem (56%). Oman also demonstrated rapid progress, increasing from 28% in 2015 to 36% in 2018. Among the reporting countries in the Arab world, only Jordan (20%) and Mauritania (24%) fall below the global average.

Women remain a minority in research

In government and academic sectors, gender parity among female researchers has been achieved in four out of ten reporting countries. Ireland took a significant step in 2018 by linking research funding from the Higher Education Authority to an institution’s success in reducing gender inequality.

However, men continue to be disproportionately represented in the business sector, characterized by higher salaries (Figure 3.5). This pattern persists even in countries that have achieved gender parity across all sectors.

Among the 73 countries with recent data available, only eight have reached gender parity in the business sector: Algeria, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mozambique, North Macedonia, Sri Lanka, and Trinidad and Tobago. Notably, women are overrepresented in the business sector in Azerbaijan, North Macedonia, and Trinidad and Tobago.

The percentage of women in the business sector remains relatively low in OECD countries, with a few exceptions such as Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Spain, where women make up approximately 30–40% of researchers in the industry.

In the business world, fewer than one in four researchers is a woman, and in some countries, the percentage is even lower, such as Germany (15%), Japan (10%), and Saudi Arabia (2%). The gender disparity is even more pronounced in engineering, where trends observed in higher education persist in the research community. Women tend to be overrepresented in medical and health sciences, humanities, social sciences, and the arts within engineering and technology research.

Only a few countries, including Azerbaijan, Kuwait, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Venezuela, have achieved gender parity among researchers in engineering and technology. The majority of countries reporting the lowest proportions of women researchers in this field are in Africa, with Japan being a notable exception, where the proportion (6% in 2015) is much lower than in any other OECD country.

Senegal is actively working to address this issue, with national research funding targeting the advancement of women through the Project for Supporting Female University Researchers in Senegal (see Chapter 17). As of 2015, 20% of Senegalese researchers in engineering and technology were women.

Women minority in the digital labour market too

Women tend to constitute a minority in the digital labour market. In the European Union (EU), for example, over half of men who earn degrees in information technology (IT) end up working in digital jobs, while only one-quarter of women do (UNESCO and Equal Skills Coalition, 2019).

This gender disparity is particularly concerning given the severe shortage of individuals with the skills required to drive Industry 4.0. Interestingly, the fields most pertinent to Industry 4.0 are also the ones where women are underrepresented in many countries, including IT, computing, physics, mathematics, and engineering.

Japan is pinning its hopes on Society 5.0, the centrepiece of its new growth strategy, to help the country adapt to a shrinking, ageing population through the widespread use of artificial intelligence (AI) and other digital technologies in industry, agriculture, and the services sector. However, the government anticipates a shortage of 300,000 general engineers in IT by 2020.