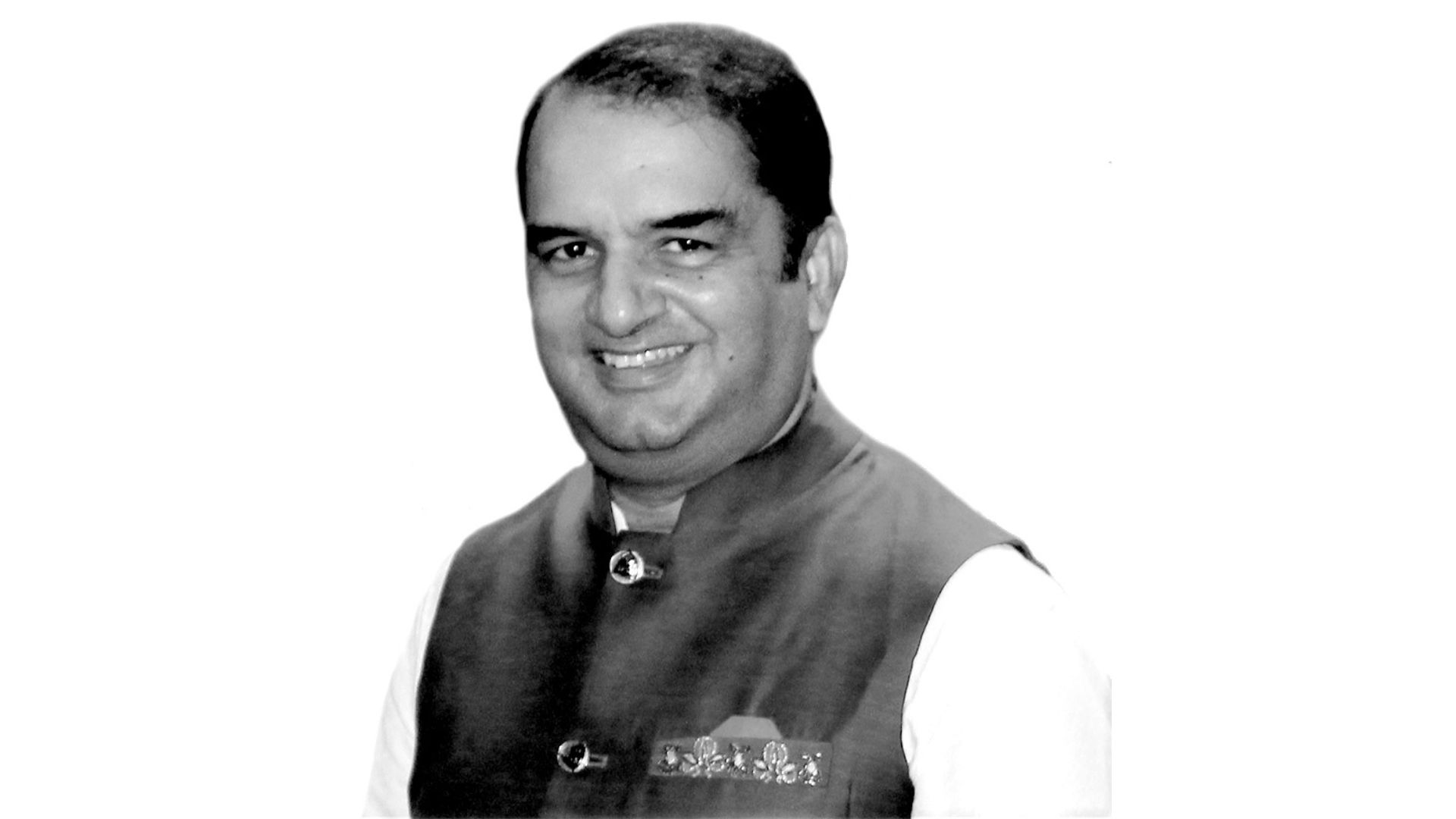

His 75th birthday (10th July) provides the perfect vantage point to look back at the pioneering life of Sunil Gavaskar. From the outset, he was a trendsetter, not just as a batsman of impeccable technique, but as a writer who taught us how to stand up for ourselves in a post-colonial world, hold our heads high amid white privilege, and demonstrate that Indians had the ability to compete with the best in any field.

Cricket was a colonial sport in which India had been happy to be an also-ran. Until the 21-year-old Gavaskar burst onto the sport’s firmament. In his first test, he made 65 and an unbeaten 67 to steer India to her first-ever test victory over the West Indies. Then he made scores of 116, 64*, 1, 117*, 124 and 220 to ensure that the door on a West Indies comeback remained firmly bolted, ensuring a series victory there for the first time.

The run accumulator had first gained renown in the 1970-71 domestic season. He made three consecutive Ranji centuries, and then piled up scores of 226, 99, 327 and 124 for Bombay University in the Rohinton Baria inter-university competition. Test selection became inevitable, and the run mountains quickly grew in the test arena too.

By the time Gavaskar had played his 50th test, he had made 20 centuries (the latest being 221 while leading an audacious attempt at chasing down 438 for victory in the final innings of the 1979 series in and against England). Nobody other than Bradman has been as quick to reach 20 test centuries.

Along the way, he led India to victory in his first test as captain, at Auckland over New Zealand in 1976. And later that year, he and brother-in-law Vishwanath each made centuries as India made a world record 406/4 in the fourth innings to fashion another famous victory over the West Indies. That, ironically, led the opposing skipper, Clive Lloyd, to adopt intimidatory tactics (as many as 4-5 bouncers in some overs) in a four-pronged pace attack that was to become the basis of one of the greatest test sides ever.

But barely halfway to the 50-test mark, Gavaskar published his candid memoirs, ‘Sunny Days’, an instant best-seller that marked the start of a second career as writer. Until then no active Indian cricketer had published his memoirs. Mushtaq Ali was the only retired Indian cricketer to have done so.

As a writer and commentator, Sunny Gavaskar has been an acute analyst of cricketing nuances. But his style of speaking — always standing up for India in the face of biased narratives – helped Indian sides to embrace and successfully conquer the power of mass media. He has also been a stickler for propriety, never abjuring the need to admonish youngsters for irresponsible play. Inspired by him, new generations made India dominant in the sport, in turn giving confidence to India to compete further afield.

As a cricketer, it was his absolute devotion to excellence that remains his greatest legacy. Immaculate in defensive technique, he was a naturally attacking batsman against pace and spin, who curtailed his natural instincts for the good of his side. When that approach occasionally failed him (as it did, for instance, in 1983), he unleashed the natural attacker at the Kotla and Motera against the might of West Indies in its fast-bowling pomp. His 29th test century (drawing parallel with Bradman) was the result, reaching the landmark off just 94 balls in a flurry of hooks, square cuts, cover- and on-drives — followed by a superb 90 on a deteriorating Ahmedabad pitch, beginning with perhaps the first-ever ramp shot over slips for four (off Holding, no less). He conquered at least three summits before any other test cricketer had: 30 centuries, 10,000 runs and 125 appearances.

Trained in the traditional copybook batsmanship of Mumbai’s maidans, Gavaskar did not take automatically to one-day cricket (which, as Vishwanath’s recent memoir also avers, Indians initially treated disdainfully). While he did relatively little with the bat during the 1983 World Cup triumph, he was key as slip fielder and elder statesman: India lost the only two games he didn’t play. And his 90 at Berbice on 29th March 1983 helped deliver a pioneering ODI victory in the West Indies’ own den that was a precursor of the two triumphs in June 1983 that transformed India’s destiny in the format.

Nothing quite became his career better than the manner of his leaving it. In his final test innings, on a fast-deteriorating pitch on which no other batsman made more than 50, Gavaskar made 96 before being given out off his elbow (not his bat or glove). In his first-class farewell (for Rest of the World against MCC at Lord’s) 38-year-old Gavaskar made 188 against Marshall, Hadlee and Rice. While his sinuous willow went silent, his wit and wisdom has continued to delight cricket fans on the airwaves and in print for the next 37 years. Happy 75th Birthday, Sunnybhai!

Prasenjit K. Basu, an economist and historian, has blogged about cricket for the past 21 years at sports-india.com