India’s linguistic diversity is unparalleled, with a history spanning millennia. Classical languages such as Sanskrit, Tamil, and Kannada have shaped the nation’s intellectual, cultural, and spiritual heritage, providing a rich foundation for literature, philosophy, and religious discourse. Despite this, many classical languages and their contributions remain underexplored in mainstream discourse. Recently, there has been growing interest in reviving and preserving these languages through digitisation, research grants, and educational reforms, although much of their history remains hidden from modern audiences.

Criteria for classical status:

To be recognised as a classical language by the Government of India, a language must meet several stringent criteria: it must have an ancient literary tradition dating back over 1,500-2,000 years, possess a body of classical literature, and show a distinct difference between its classical form and its modern spoken version. Tamil was the first to receive this recognition in 2004, followed by Sanskrit, Telugu, and Malayalam, among others.

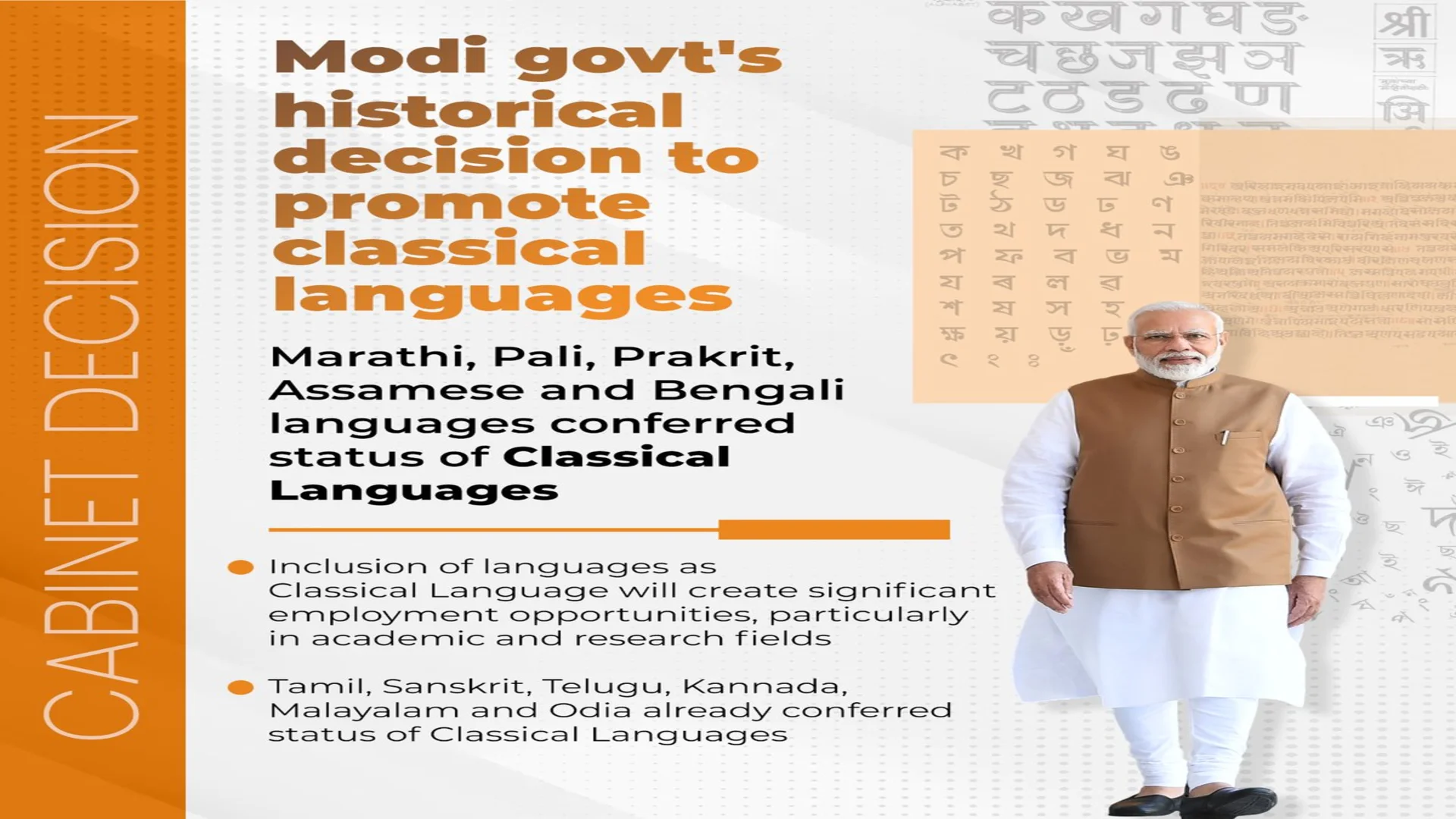

Recently, the recognition of Marathi, Bengali, Assamese, Pali, and Prakrit as classical languages highlights the ongoing efforts to acknowledge the historical significance of these languages. The Union Cabinet’s decision has sparked renewed attention toward the preservation of ancient manuscripts, academic research, and cultural tourism related to these languages. For instance, the addition of Pali—a key language for Buddhist scriptures—has rejuvenated interest in studying ancient Buddhist texts and philosophies, particularly in countries like Myanmar, Thailand, and Sri Lanka, which share this cultural heritage.

Historical and political movements behind the decision:

The recognition of these languages follows a long-standing demand from various linguistic communities. For example, the demand for Marathi to be granted classical language status began over a decade ago, with the Maharashtra government submitting a proposal in 2013. Political leaders from Maharashtra have continually pressed for this recognition, viewing it as essential for promoting Marathi culture and linguistic pride. Similarly, West Bengal, Assam, and Bihar have lobbied for the inclusion of Bengali, Assamese, and Pali, respectively, citing the historical and cultural significance of these languages. In 2024, after consultations and revisions to the criteria, the Linguistic Experts Committee (LEC) recommended the classical status for these languages, which was finally approved by the Union Cabinet.

How classical language status changes things:

Preservation of ancient texts and knowledge: One of the most significant benefits of classical language status is the preservation of ancient literary works and manuscripts. With this recognition, languages such as Pali and Prakrit, which are critical for understanding Buddhist and Jain traditions, will see increased efforts in digitizing and conserving ancient texts. This provides access to future generations of scholars and promotes global research into India’s intellectual and cultural history.

Cultural and academic growth: The classical status promotes academic research by introducing specialized courses in universities and increasing funding for language studies. For example, after the recognition of Tamil as a classical language in 2004, the Central Institute of Classical Tamil was established to support scholarly research and translation efforts. A similar trajectory is expected for the newly recognized languages, creating opportunities for research centres and scholarships dedicated to these linguistic traditions.

Political and regional pride: The recognition of classical languages often serves as a political victory for regional leaders and communities, reinforcing regional identity. In the case of Marathi, for instance, this recognition strengthens the cultural pride of the people of Maharashtra, affirming their language’s importance in India’s historical and literary landscape. This regional pride often intersects with broader cultural preservation efforts, leading to a revitalization of traditional art forms, literature, and local festivals.

Economic impact through cultural tourism: The recognition of classical languages also has economic implications, particularly in the tourism sector. Cultural heritage sites, such as those linked to Assamese and Bengali literature or ancient Pali inscriptions, are likely to receive increased attention from both domestic and international tourists. This boost in cultural tourism not only helps local economies but also encourages investment in heritage preservation

The forgotten texts and their influence beyond India:

While Sanskrit and Tamil have received considerable scholarly attention, texts in Prakrit, Pali, and Assamese are less studied but equally valuable. Prakrit, for example, was the language of Jain literature, with the Agamas being central religious texts, while Pali is integral to Buddhist teachings. These languages influenced not just Indian scholars but also had a significant impact across Southeast Asia.

Ancient Buddhist texts written in Pali, such as the Tipitaka, influenced the development of Theravada Buddhism in countries like Thailand and Myanmar. Similarly, Prakrit literature, particularly Jain texts, travelled across regions, influencing local cultures in present-day Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

The undeciphered scripts and their mysteries:

India’s classical languages are further enriched by ancient scripts that remain undeciphered, such as the Indus script. This script, found in the ruins of the Harappan civilization (2600-1900 BCE), is yet to be fully decoded, despite decades of research. The potential breakthroughs in deciphering the Indus script could unlock a deeper understanding of the early urban societies of the Indian subcontinent.

Similar to how the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in Egypt led to the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs, there are hopes that a key discovery could help unlock the meaning of the Indus symbols. Ongoing efforts, such as those by Iravatham Mahadevan, an expert in Indian epigraphy, continue to generate new leads.

The evolution of scripts:

India’s classical languages are also deeply tied to the evolution of scripts such as Brahmi and Kharosthi. These ancient scripts laid the foundation for many modern Indian scripts, including Devanagari and Tamil-Brahmi. Brahmi, in particular, is known for its inscriptions on Ashoka’s edicts, which date back to the 3rd century BCE.

The Brahmi script’s spread across Asia, especially through Buddhist texts, influenced the development of scripts in countries like Thailand and Cambodia. The use of Brahmi by Emperor Ashoka to propagate his edicts marked one of the earliest uses of writing for governance and public communication.

Demand for recognition of other languages:

There is an ongoing movement to grant classical status to more Indian languages, such as Maithili and Meitei. Recognition is not just a matter of academic prestige but also one of cultural pride and identity. For instance, Meitei speakers in Manipur have long demanded classical language status for their ancient language, citing its historical significance and rich literary tradition.

Scholars from Bihar have similarly advocated for Maithili, a language with a documented literary history dating back to the 7th century CE. Texts like Vidyapati’s poetry are celebrated in both India and Nepal, highlighting the cross-border cultural heritage of the language.

Role of classical languages in modern society:

Classical languages continue to play a crucial role in shaping modern India’s identity. With the growth of cultural tourism, sites associated with these languages—such as the Ajanta and Ellora caves, which contain inscriptions in Prakrit and Sanskrit—have become focal points for heritage tourism.

Additionally, the digitization of classical manuscripts has gained momentum. The National Mission for Manuscripts and international collaborations, such as the Sanskrit Manuscripts Project at Cambridge University, is making these texts accessible to scholars and the general public. For example, the ongoing digitization of Sanskrit and Tamil texts is helping preserve these cultural treasures for future generations.

Economic Impact: The push to digitize and promote classical languages has also spurred job creation in areas such as manuscript preservation, translation, and cultural tourism. The increased visibility of classical languages in the global academic community has opened new opportunities for researchers, translators, and digital archivists.

Impact on education:

Classical languages are experiencing a revival in Indian and global academia. Historically, institutions like Nalanda University were hubs for scholarly pursuits in Sanskrit, Pali, and other classical languages. Today, universities like JNU and BHU offer advanced degrees in Sanskrit and Tamil, while foreign universities such as Harvard have established dedicated chairs in these languages.

However, classical language studies face hurdles, such as declining student interest and inadequate funding. Scholars have suggested incorporating classical languages into interdisciplinary programs that combine linguistics with fields like philosophy and AI to attract a younger generation.