Even as the first round of voting begins for 18th Lok Sabha, the politically surcharged atmosphere has every flavour of the season. The Central Election Commission has huge resources and powers to supervise polls but lacks spine and a will to act as impartial observer. Instead, it acts more like an observer, often reacting to the events and trying to do a balancing act instead the call of a spontaneous call of conscience seeped in propriety.

The Election Commission has a constitutional duty to act as a referee and all powers to exercise. But the three- member commission appears listless, careless, off-the-field third empire who occasionally wakes up from deep slumber or at the prodding of social and mainstream media to make its presence felt.

What is more glaring is the EC’s method of punishment. During 2019 Lok Sabha polls, the election commission had ‘penalised’ Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath for raising a bogey of “Bajrang Bali versus Hazrat Ali.” Next, the election commission saw Adityanath’s image beaming across tv news channels chanting Hanuman Chalisa during the supposed ban period. A somewhat triumphant Yogi had told CNN-News 18’ then, “I was punished for taking Bajrang Bali’s name. I chanted it for the period I was banned”!!

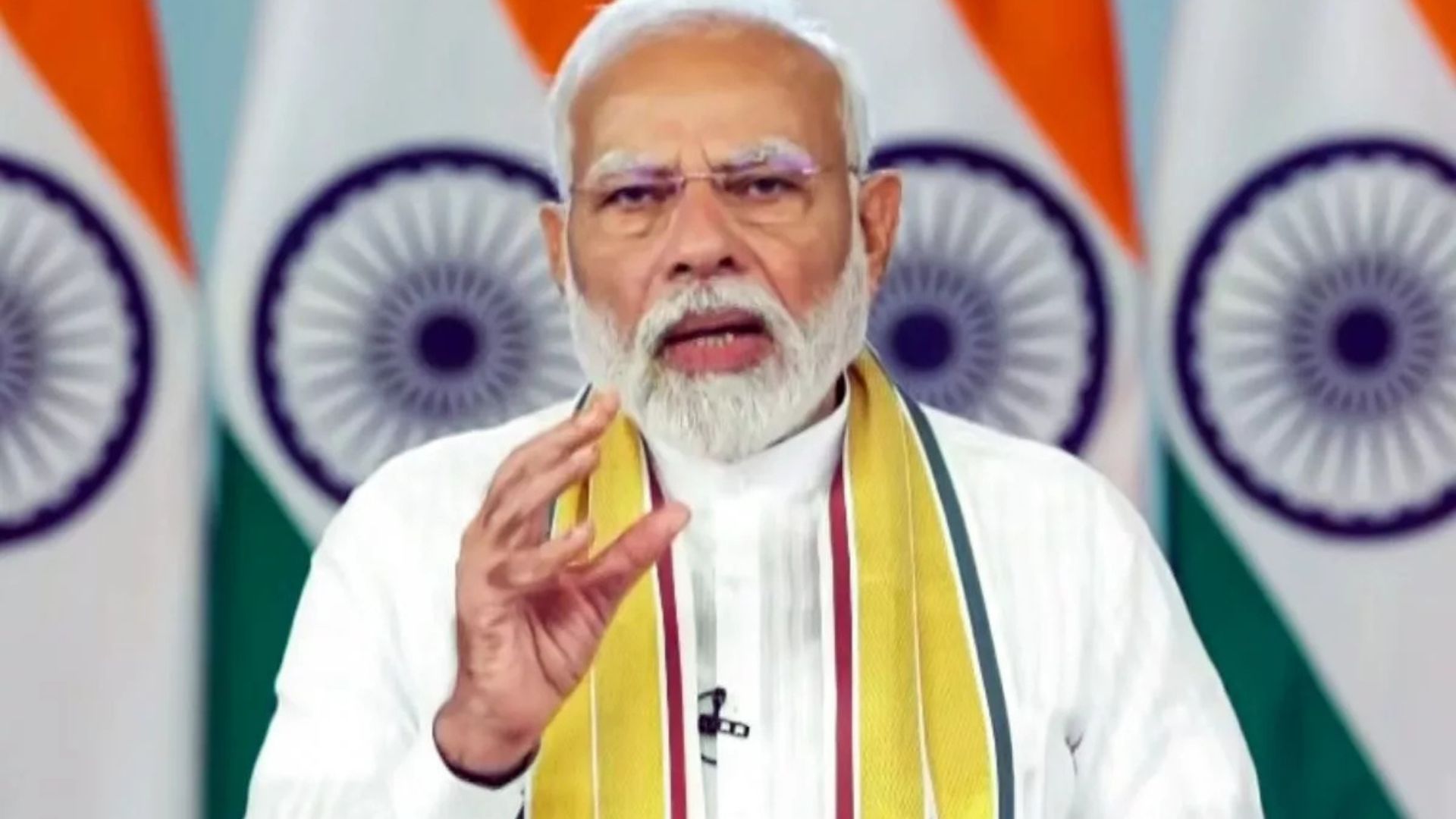

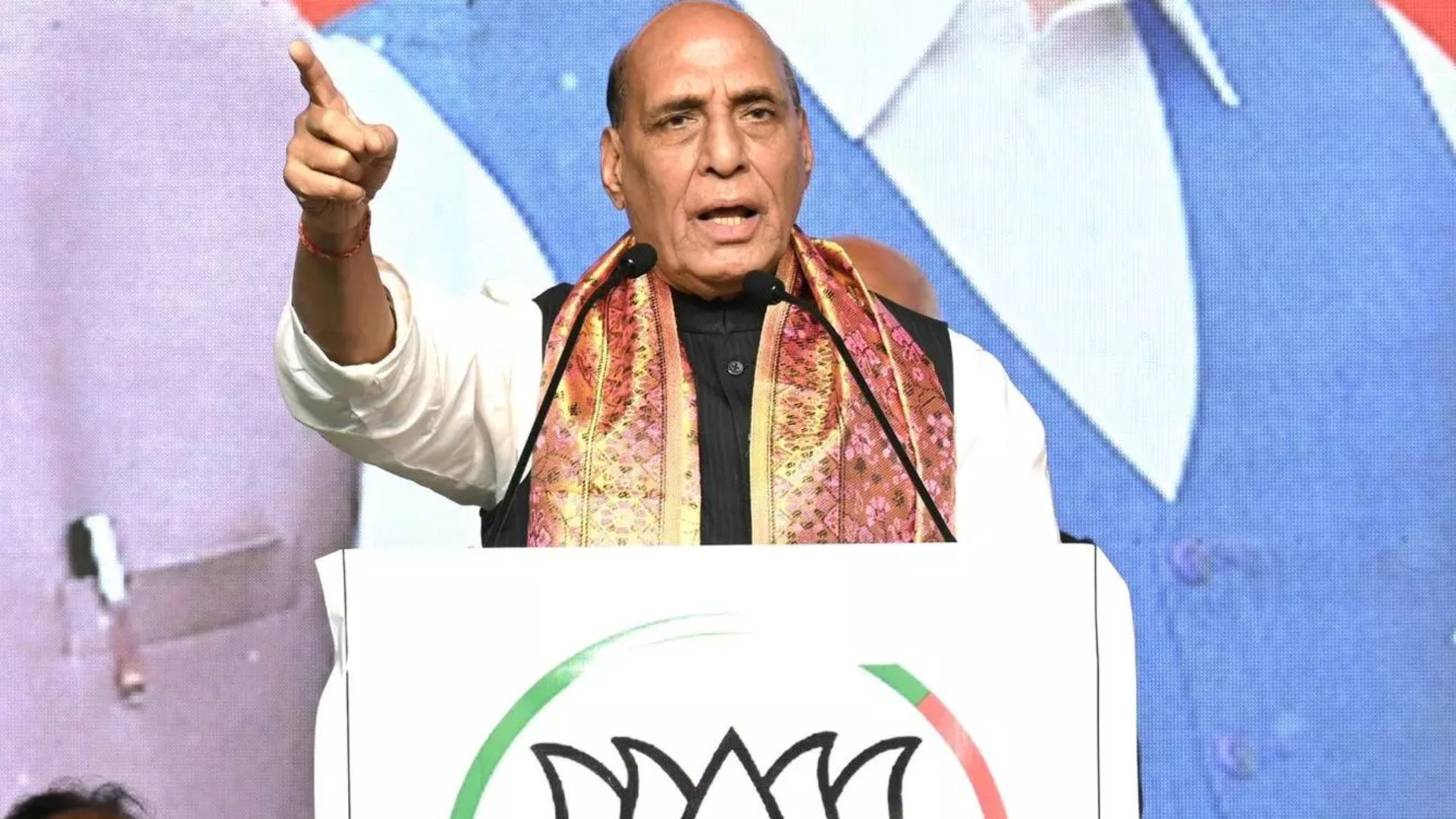

Political leaders, mainly in the opposition ranks, accuse EC of being proactive against them, letting off the prime minister Narendra Modi, BJP and the NDA.

Toxic campaign is not alone where the election commission is seen as a hopeless, helpless, mute spectator. The government of the day has gone about conducting ED, CBI and income tax raids on many opposition leaders individuals considered sympathetic to them.

EC inaction is in sharp contrast to its assertiveness in 2014 when it had recommended postponing certain policy decisions of the government related to natural gas pricing and notifying ecologically sensitive areas in the Western Ghats. The EC had invoked the Model Code of Conduct (MCC).

It is pertinent to examine what is the Model Code of Conduct? As I had tried explaining in a 2019 article for the Money Control, the MCC, mentioned in the article 324 of the Indian constitution, is a set of guidelines issued by the Election Commission to regulate political parties and candidates prior to elections, to ensure free and fair elections. The Constitutional provision gives the Election Commission the power to supervise elections and the MCC becomes operational from the date that the election schedule is announced till the date that results are announced.

The MCC was first introduced in the state assembly elections in Kerala in 1960 as a set of instructions to political parties regarding election meetings, speeches, slogans, etc. In the 1962 general elections to the Lok Sabha, the MCC was circulated to recognised parties, and state governments sought feedback from the parties.

The MCC was largely followed by all parties in the 1962 elections and continued to be followed in subsequent general elections. In 1979, the Election Commission added a section to regulate the ‘party in power’ and prevent it from gaining an unfair advantage at the time of elections. There are eight key provisions of the Model Code of Conduct dealing with general conduct, meetings, processions, polling day, polling booths, observers, party in power, and election manifestos. It includes issues like how one political party should criticise the other. The Criticism should be confined to their policies and programmes, past record and work. Activities such as: (a) using caste and communal feelings to secure votes, (b) criticising candidates on the basis of unverified reports, (c) bribing or intimidation of voters, and (d) organising demonstrations or picketing outside houses of persons to protest against their opinions, are prohibited. Even a cursory look at four phases of electioneering would show that none of these provisions were followed. There was no semblance of any MCC anywhere.. be it NDA partners of UPA allies or regional leaders.

It must be remembered and emphasized that Westminister model of parliamentary democracy has issues of propriety at premium. MCC therefore, is based on assumption that political parties and candidates would accord importance to issue of propriety, ethics and morality. In the absence of these lofty principles, Westminister model is reduced to ashes. Britain, cradle of parliamentary democracy, has no written constitution. political defections are rare and conventions have greater say than rules and laws. The Indian experience is the reverse of it. MCC, without a stringent legal cover, is impractical and toothless.

Indian political parties, courts, media and other sections of society need to ponder over issues of electoral malpractices and revisit the entire issue of functioning of EC, applicability of MCC, electoral reforms and host of other issues. It is a cruel joke that poll expenses in a parliamentary polls (having over a million voters) has a ceiling of rs 75 lakhs amounting to a candidate spending 70 paisa on every voter! In effect, the system has made every candidate and elected representative corrupt and unlawful.

The Election Commission needs to be made broad-based, accountable and transparent. Members of civil society, prominent citizens, retired members of judiciary should have lateral entry in state and central election bodies instead of a forum of pliable babus. The MCC needs to be overhauled and rewritten so that there is extensive discussion in the public domain before it is implemented. If poll expenses limit is required to be increased to rs five crore and more, so be it. Public funding of polls is another area that requires debate, discussion and possible implementation. But is there a political will that is not guided by political gains? That is the real test for Indian democracy.

Old hands in Nirvachan Sadan also favour induction of a retired Supreme Court judge in the Central Election Commission. There is a merit in it as ECI performs several important functions which are quasi-judicial in nature such as dealing with the crucial issue of the disqualifications of MPs and MLAs, petitions and interpretation of rules in the Representation of Peoples Act etc. the idea of ECI decisions getting overturned regularly is not healthy. Often, the ECI’s opinions are binding on the President and Governors, therefore, there is a greater need for legally sound advice.