It is hard to make a distinction between talent and genius. Even then some differential psychologists and philosophers made occasional attempts but the exact measure of success attained remains somewhat doubtful. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer made one such attempt. According to him, “Talent hits a target no one else can hit; Genius hits a target no one else can see”. But in common parlance, this distinction does not find its ready expression. In fact, the two terms have been used interchangeably for a long time. Though it is believed that both are evenly distributed in a sizeable population but in practice, some countries seem to have them more in number than others. One might call them with whatever names, they are the ones whose scholarships have brought the civilization thus far and would continue to move it forward. India is known to have produced very many such scholars from the very earliest times. They have left behind a legacy of strong leadership in their respective areas of expertise. Life and work of such geniuses stand as a testament to their indomitable will and the courage to practice the ideals that they preached. The general populace would be proud in knowing about their remarkable contributions that have a significant bearing on education.

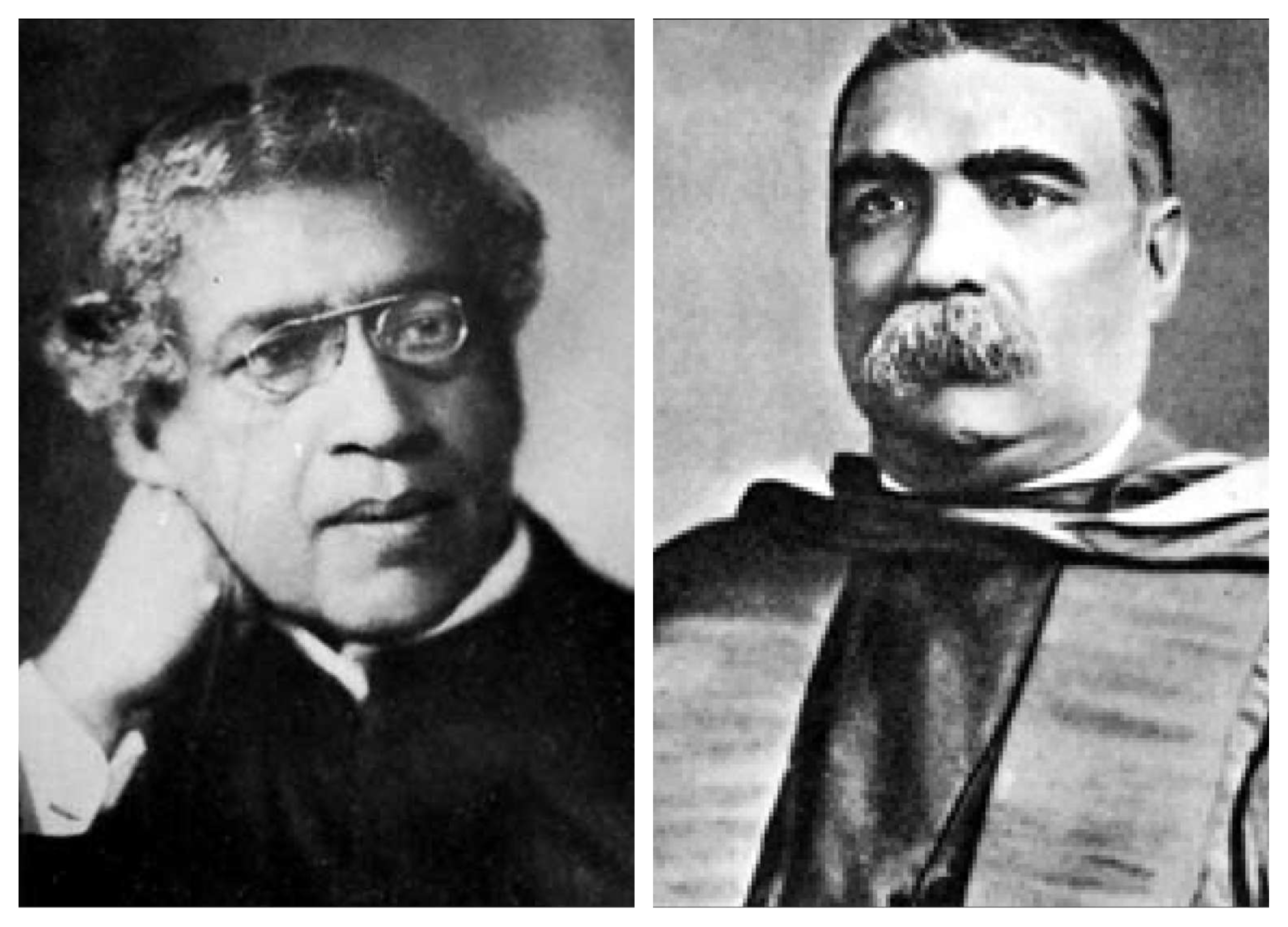

It should be the bounden duty of educational institutions to educate the coming generations with the life and work of such inspirational scholars. Two such contemporaries who had experienced a long and profoundly productive career in education and left a unique and indelible imprint happened to be Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose and Sir Asutosh Mukherjee. Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose was born in Munsiganj, Bengal Presidency on 30th November, 1858, and Sir Asutosh Mukherjee was born on 29th June, 1864 at Kolkata. Although they were born in affluent and scholarly families yet they were sent to vernacular schools because of the firm conviction of their parents to study in their own mother tongue, to know their own people and to be at one with them. Both of them were extraordinarily talented with different dreams but had one thing in common, that they were deeply and passionately committed to excellence.

Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose wanted to go to England to compete for the Indian Civil Services but aborted his plan thinking that he would like to be a scholar ‘who would rule nobody but himself’. He was a multifaceted personality. He was incredibly knowledgeable in different fields of study. He was a physicist, biologist, botanist, and science fiction writer. He was known as one of the fathers of radio science. He became the most prominent first Indian scientist who proved by experimentation that both animals and plants share much in common. He demonstrated that plants were also sensitive to heat, cold, light, noise, and various other external stimuli, research of far-reaching depth of that time. Interestingly, he explored this phenomenon out of the burning curiosity that was aroused by his mother in him when she forbade him not to pluck ‘Tulsi’ leaves after sunset, as she had a belief that like humans the aromatic plant also goes to sleep after sunset. He had a very fertile mind full of original ideas. He had given his views on several concerns which have a strong bearing on education.

In his address to the Royal Society of Arts, London in 1896, Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose pointed out that “The present system of university education does not foster the proper development of intellectual faculties and encourage originality. The exercise of mere memory at the expense of the other faculties cannot but be attended with disastrous consequences. When the brain is crammed with a mass or apparently disconnected facts, without any order or sequence, the state of equilibrium becomes highly unstable, and the shock of an examination is enough to upset it”. This address of his drew enthusiastic applause from a formidable audience. This was such an apt address that even today it is applicable, in one form or the other, to Indian higher education system.

Acharya Bose wanted students of science to learn how to use their hands, how to observe and how to avoid errors and as far as possible, to find out things for themselves, and take very little on trust. He wanted them to feel that science and scientific experiments are not merely confined to the laboratories, but that in nature around them experiments of surpassing interest are being constantly carried out if they would only see them. He was of the view that no real progress in science is possible in a country unless it aspires to take its due share in general advancement of science. He believed that the cause of science is international and scale of its benefits are universal.

Acharya Bose was of the view that “the highest expression in the life of a nation must be its intellectual eminence and its power of enriching the world by advancing the frontiers of knowledge. Discovery of truth was always at the heart of his intellectual endeavour. According to him, “Two different methods are essential for the discovery of truth, the method of introspection and the method of experimental verification. Aimless experimentation seldom leads to any great result, while unrestrained imagination leads to wildest speculation subversive of all intellectual sanity. The two methods must, therefore, be equally balanced, one supplementing the other”.

Acharya Bose was of a strong view that literature and science have a symbiotic relationship. In the multiplicity of phenomena he felt that one should never miss underlying unity and apprehend no insuperable obstacle in grasping it. He believed that both the poet and the scientist are set out for the same goal, that is, to find unity in the bewildering diversity. He believed that the status of a great university could not be secured by any artificial means, nor could any charter assure it. Its world status is only to be won by the intrinsic value of the great contribution made by its scholars. He desired that to be organic and vital, our national university must stand primarily for self-expression and winning for India her true place among the federation of nations, a guiding principle worth emulating.

Sir Asutosh Mukherjee was another legend of the same era. He was the first student of the university of Calcutta to earn double Masters degrees in physics and mathematics. He was the first Indian Vice-Chancellor who broke the colonial tradition of not letting Indian universities to have post-graduate departments for teaching and research on their campuses. He wore many hats during his long and eventful career, as a barrister, jurist, mathematician, educator and Vice-Chancellor. He remained the Vice-Chancellor of university of Calcutta for four consecutive two-year terms (1906-1914) and a fifth two-year term (1921-23). He was incredibly intelligent and bold. He had published his first research paper on Geometrical Theorem in the Messenger of Mathematics, Cambridge at the age of 17. It may be pertinent to know of Sir Asutosh Mukherjee in the words of Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore,“Men are always rare in all countries through whom the aspiration of their people can hope to find its fulfilment, who have the thundering voices to say that what is needed shall be done; Asutosh had the magic voice of assurance. He had the courage to dream because he had the power to fight and the confidence to win — his will itself was the path to the goal”. It was because of these qualities of his that he was called the tiger of Bengal.

He pleaded for the freedom in the university, freedom in its inception, freedom in its administration, and freedom in its expression as he felt strongly that this is the very condition of vigorous existence in an institution engaged in the search for truth. He made fervent appeal to keep the universities free from the baneful influence of dogmas, whether they be official, political, religious or academic. He frankly recognized the kinship of the arts and sciences and the inherent interdependence of all study and research, supplement theoretical and professional instruction by organic connection with arts and letters. He said that he could imagine no step more unwise for an Indian university to take than to give exclusive prominence to studies peculiarly Indian.

In his convocation address to university of Calcutta in 1908, Sir Asutosh Mookerjee referred to a fundamental doctrine which he perceived lies at the root of university system of education and that referred to the medium of English in higher education. He was of the view that western life should reach us through western gates and not through latticework in eastern windows. He observed that the validity of this principle has not been seriously questioned. Academic freedom according to him, is a pre-requisite to self-education and culture. He appealed to young students not to submit to intellectual slavery and not to abandon their most priceless possession to test to doubt to see everything with their own eyes.

His oratorial scholarship and courage would continue to inspire the academic fraternity. He was a charming talker, with gay humour and a quite sarcasm. There is an interesting anecdote that relates to his accidental participation in a debate that was hosted by the university of Lucknow in 1924. The proposition of the debate which had been framed was, “That, in the opinion of this House, the Ministers and the Councils are justified in exercising control over the administration of the Universities.” He excelled in demolishing the proposal for the motion. It is not only difficult to summarise but also would not be wise to do so. Every argument he made led to losing of the motion by an overwhelming majority. The flavour of the arguments would necessitate going through the arguments the way they were presented by him. The force of his arguments is a pleasurable treat to hear on a subject of extreme relevance even today.

Although the areas of operation of Acharya Jadgish Chandra Bose and Sir Asutosh Mukherjee were different but there were many similarities between the two. They were independent minded and intellectually curious men. Both of them were extremely conscientious regarding their duty. They served humanity with selfless devotion and left behind a legacy that is enormous. The present generation of academia, as well as youth, can learn a great deal and draw inspiration from the eventful lives of these two contemporary intellectual giants.

The government may consider commissioning a project to bring out an anthology representing the quintessence of the life and work of eminent scholars India has produced and then make it available through NCERT and UGC to all schools, colleges, and universities. It would serve a double purpose. First, it would let the coming generations pay the greatest respect and reverence to the inspirational leaders of the academic world, and second their pioneered ideas and remarkable achievements would inspire posterity. Such a compilation would not only be worth a good read but could be a life-changing material for those who have a burning desire to succeed and leave a name behind.

The writer is former Chairman, UGC. The views expressed are personal.