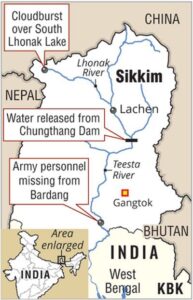

A study by an international team of researchers had warned two years ago that the South Lhonak Lake in Sikkim may burst in the future and “significantly impact the downstream region”. An outburst in the South Lhonak Lake on the intervening night of 3-4 October, triggered a flash flood in the Teesta river basin, leaving 14 people dead and 102 others—including 22 army personnel—missing. The event also resulted in the breach of the Chungthang dam, which is the largest hydropower project in Sikkim. The 2021 study, published in the journal Geomorphology, highlighted that South Lhonak Lake had witnessed significant growth in the past decades due to glacial retreat, thereby increasing its chances of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF). GLOFs occur when lakes formed by melting glaciers suddenly burst open. This can happen due to various reasons, such as too much water accumulating in the lake. Studies show that the glacier receded about 2 kilometres in 46 years from 1962 to 2008. It further retreated by about 400 metres from 2008 to 2019.

The Teesta basin in Sikkim Himalaya hosts numerous glacial lakes in the high-altitude glacierised region, including South Lhonak Lake, which is both the largest and fastest-growing lake in the area. Sikkim has 733 glacial lakes, with 288 located above an altitude of 5,000 metres, according to Hyderabad-based National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC). The South Lhonak Lake is located at 5,200 m (17,100 ft) above sea level and was formed due to the melting of the Lhonak glacier. The research team—which includes scientists from the Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee and the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore—found that while these lakes are mainly located in remote and unsettled mountain valleys, far-reaching GLOFs may claim lives and damage assets up to tens of kilometres downstream; this can be seen now as the state of Sikkim grapples with flash floods.

The researchers noted that the Central Water Commission initiated an advisory to evaluate the condition of the lake system. The initial hazard assessment of the South Lhonak Lake based on the conditions then also suggested that the lake had a great potential to impact the downstream region significantly. A study published in the journal Nature earlier this year stated that 15 million people worldwide are exposed to potential GLOF impacts. Populations in High Mountains Asia (HMA) are the most exposed, living closest to glacial lakes, with one million people living within 10 km of a glacial lake. More than half of the globally exposed population is found in just four countries: India, Pakistan, Peru, and China.

STUDY FINDINGS

GLOFs occur when lakes formed by melting glaciers suddenly burst open. This can happen due to various reasons, such as excessive water accumulation in the lake or triggers like earthquakes. When the lake bursts, it releases an enormous volume of water all at once, causing flash floods downstream. These floods can be extremely destructive and dangerous for the affected area’s people and the environment.

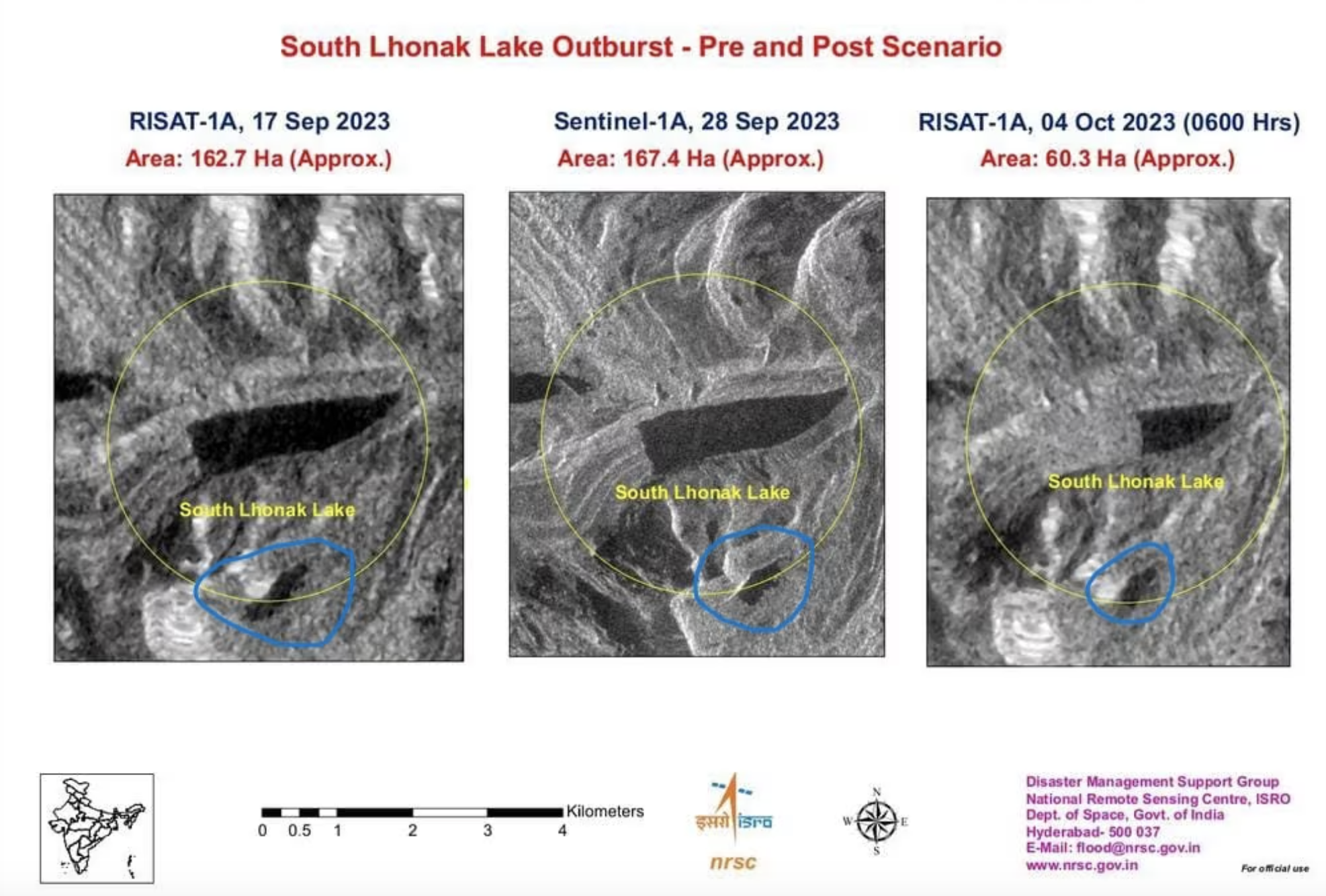

As for the South Lhonak Lake, its size has been rapidly increasing due to the melting of the lake’s associated glacier and additional meltwater from the adjacent North Lhonak and main Lhonak glaciers. Satellite images from the Hyderabad-based National Remote Sensing Centre showed that the area of South Lhonak Lake drastically reduced from 167.4 hectares on 28 September to 60.3 hectares on 4 October, confirming a GLOF event that caused massive damage in the Teesta River basin. A study conducted by the National Remote Sensing Centre and the Indian Space Research Organisation in 2012-2013 discussed the formation of a moraine-dammed glacial lake at the snout of the South Lhonak glacier and the associated risks. “The (South Lhonak) lake outburst probability shows a very high value of 42 percent for the lake, and the peak discharge estimated using the empirical formula shows a discharge of 586 m3/s,” the study said.

In 2016, the Sikkim government’s Department of Science and Technology conducted an expedition to estimate the lake’s volume—the team warned about the potential of a GLOF event. In September this year, officials from the DST, SSDMA, and the Land and Revenue Department conducted another inspection at the lake to install an early warning system and automatic weather station. A study published in the journal ELSEVIER in 2021 identified South Lhonak Lake as potentially dangerous with a high outburst probability.

“In Sikkim, the lake-terminating glaciers have shown accelerated growth compared to glaciers without lakes. South Lhonak Glacier is no different; it is one of the fastest-retreating glaciers, and the associated proglacial lake (south Lhonak Lake) has become the largest and fastest-growing in the state. The glacier receded approximately 2 km in 46 years from 1962 to 2008 and retreated another 400 m from 2008 to 2019.

This has raised concerns about the hazard potential of this lake, as the downstream valley is heavily populated with numerous settlements and infrastructure,” the study highlighted. The Sikkim Human Development Report of 2001 also cautioned about a “serious potential hazard” from GLOFs in Sikkim. “Disturbances in mountain ecology have started attracting considerable attention. The phenomenon of jokulhlaup (glacier leap), also known as glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF), is a frequent and alarming occurrence in Sikkim. As the state is dotted with many glaciers, this is a serious potential hazard,” the report read.

CONTAMINATION RISKS

Floods heighten the risk of dying in the three to six weeks window following the event, new research in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) says. The risk of death in general increased by 2.1 percent, whereas that in people having heart and lung illnesses increased by 2.6 and 4.9 percent, respectively, a team of researchers has found. This increased risk peaks for around 25 days, but persists for up to 50-60 days after the first day of flooding, they said in their study, having studied deaths in 761 communities from 35 countries that experienced at least one flooding event from 2000 to 2019. In the aftermath of a flood, the risk of death from natural causes could be enhanced due to contamination of food and water, exposure to disease-causing fungi, bacteria or virus, impaired access to health services, and psychological impairment.

These flood-and-death associations varied with local climate type and were stronger in populations with low socioeconomic status or high proportions of older populations. The team analysed a total of 47.6 million deaths from all causes, 11.1 million cardiovascular deaths, and 4.9 million respiratory deaths. Against the backdrop of climate change, flooding events, which account for nearly half (43 percent) of all natural disasters, are projected to become more severe, longer and more frequent. Roughly 23 percent of people are directly exposed to inundation depths of over 0.15 metres every decade, the researchers said.