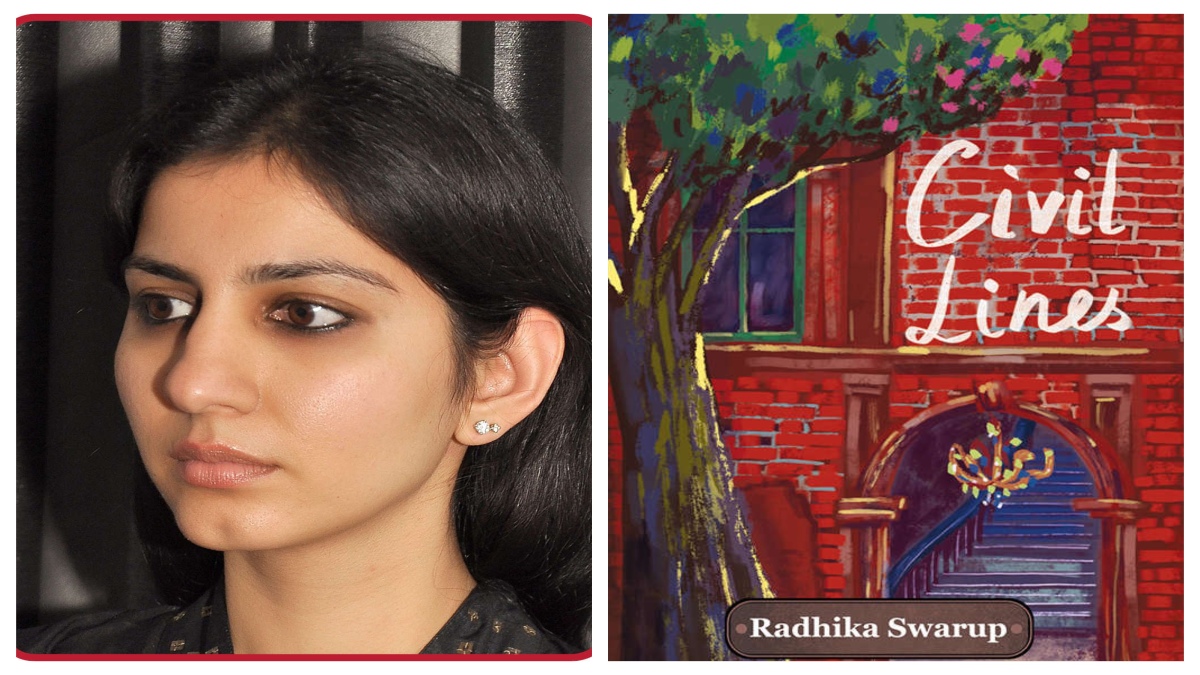

Radhika Swarup’s Civil Lines brings together several topical issues and sends out an important message in the wake of the MeToo movement.

When Maya and Siya Sharma start the monthly magazine The Satirist out of their crumbling residence in Civil Lines, they not only resurrect their late mother’s dream but also unearth a secret which lay at the core of their relationship with each other. With the Sharma women’s haunting family saga, presented in her new book, Civil Lines, Radhika Swarup sends out a message of hope and empowerment to women who dream of a brighter, safer future.

In an interview with The Sunday Guardian, the author discusses her new book and what inspired it. Excerpts:

Q: Civil Lines presents a powerful and uplifting story in the post-MeToo era. What led you to broach that subject in the book?

A: I had been thinking for some time of writing about a family haunted by their mother’s trauma, but the precise contours of the story weren’t clear to me. Then the Me Too saga began to unfold in 2016. Suddenly people were talking more about these issues, and everything fell into place; a bereft Rupa Sharma, a decaying house, a diffident Maya, an isolated Siya.

I saw how someone like Rupa, articulate, proud and assertive, could have allowed her life to be contained in a house that crumbled around her. Writing the novel so long after the defining event of the book had taken place also allowed me to delve into the long-reaching and lasting damage a ‘casual’ overture can have and to show how perpetrators can continue to paint themselves as victims.

When I began to write the book though, I knew I couldn’t leave the house in disrepair or the sisters estranged. They all felt like such a metaphor for a truncated way of life and for a country that has endured—and overcome—so much that I knew the book had to have a hopeful ending. The recent court ruling acquitting journalist Priya Ramani bears out my belief in this justice.

Q: From crafting the central characters to dealing with tough subjects like sexual harassment and trauma, what sort of emotional investment did the book require from you as an author?

A: Writing the book was a form of catharsis. I’ve always found writing to be a release, and as I saw the MeToo movement unfurl across the world from 2016 onwards, I was angered not only by the universality of the powerful abusing the weak but also disheartened by the apparent lack of any real or lasting solutions. There was some performative outrage, but there were always so many apologists for the perpetrators, and so many people who cast aspersions on the victims. When it came to writing Civil Lines though, the fates of my protagonists were largely in my hands, which was empowering. I say largely as my characters didn’t always behave as I first conceived. Tasha-di, for instance, initially rationalises the abuse her best friend suffers, but understanding her viewpoint was important for my writing journey too. It was useful for me to see that someone I disagreed with so fundamentally was essentially good and well-intentioned.

Q: Why did you choose to set the novel in Delhi? What is the significance of a decaying house in Civil Lines?

A: The genesis of the novel lies not so much in Delhi but in a Delhi house I visited some years ago. It was in a sad state of disrepair and a powerful feeling of melancholy pervaded its walls. It got me thinking about what could possibly have led its owners to allow it to decay so badly, and I’m not talking about not being houseproud, but about allowing damp and dirt to flourish in a home, and about allowing peeling plaster and exposed wires to assert control. I kept thinking of the house long after I had left it, and I kept wondering about the fortunes of its inhabitants, who appeared to me to have simply lost hope in life.

And, of course, in a rapidly changing and modernising India, a neighbourhood called Civil Lines remains a constant in most cities. It is synonymous with inherited privilege, and equally, with a sort of irreversible decay. I was interested in exploring the idea of an old house, of imagining an old way of life still being lived as the world changed around it, and as the Sharma women came into the frame, I became consumed with the idea of the house decaying as Rupa Sharma’s life disintegrated. The name of the area—Civil Lines—also felt poignant against the backdrop of the type of journalism the sisters were trying to espouse.

Q: Does The Satirist as a motif indicate the need for honest and fearless reporting and writing in the world today?

A: Honest and fearless journalism is always needed, and as you note, The Satirist attempts to shine a light on stories that are often overlooked. The truth is that we have all become a little tribal and a little more thin-skinned of late. Social media hasn’t helped as it has allowed the shrillest to be handed a megaphone. Having said that, I see debate and dissent flourishing across the world, as they must. This holds true for the proudest democracies and for the more authoritarian parts of the world, and in that I see some promising torchbearers for The Satirist.

Q: What would you like the reader to take back from Civil Lines? Would you say fiction is an effective tool of driving home an important message?

A: I fervently believe that fiction allows people to inhabit another’s skin, and in so doing, allows them to understand another’s perspective. That empathy is so often lacking in today’s partisan discourse, but I took great heart when my debut novel, Where the River Parts, which looked at Partition, was read and appreciated by people across the political divide.

I hope for the same fate for Civil Lines, and in that vein, I hope for it to be read not only as a woman’s novel but as a deeply human one. I hope that people who wouldn’t normally be able to understand the compulsions of a Rupa Sharma—the feudal matriarchs, the fathers of sons, the school child with their life stretching out before them and, yes, the powerful man—are able to walk a little in her shoes and feel for what her life was.

Q: What are you writing next?

A: I’ve been writing a series of linked short stories about the neighbourhood I grew up in in Delhi. I’ve been unable to visit India for over a year due to the pandemic, and so my mind has invariably been occupied by thoughts of family and home. It is a love letter of sorts to the Delhi of my childhood.