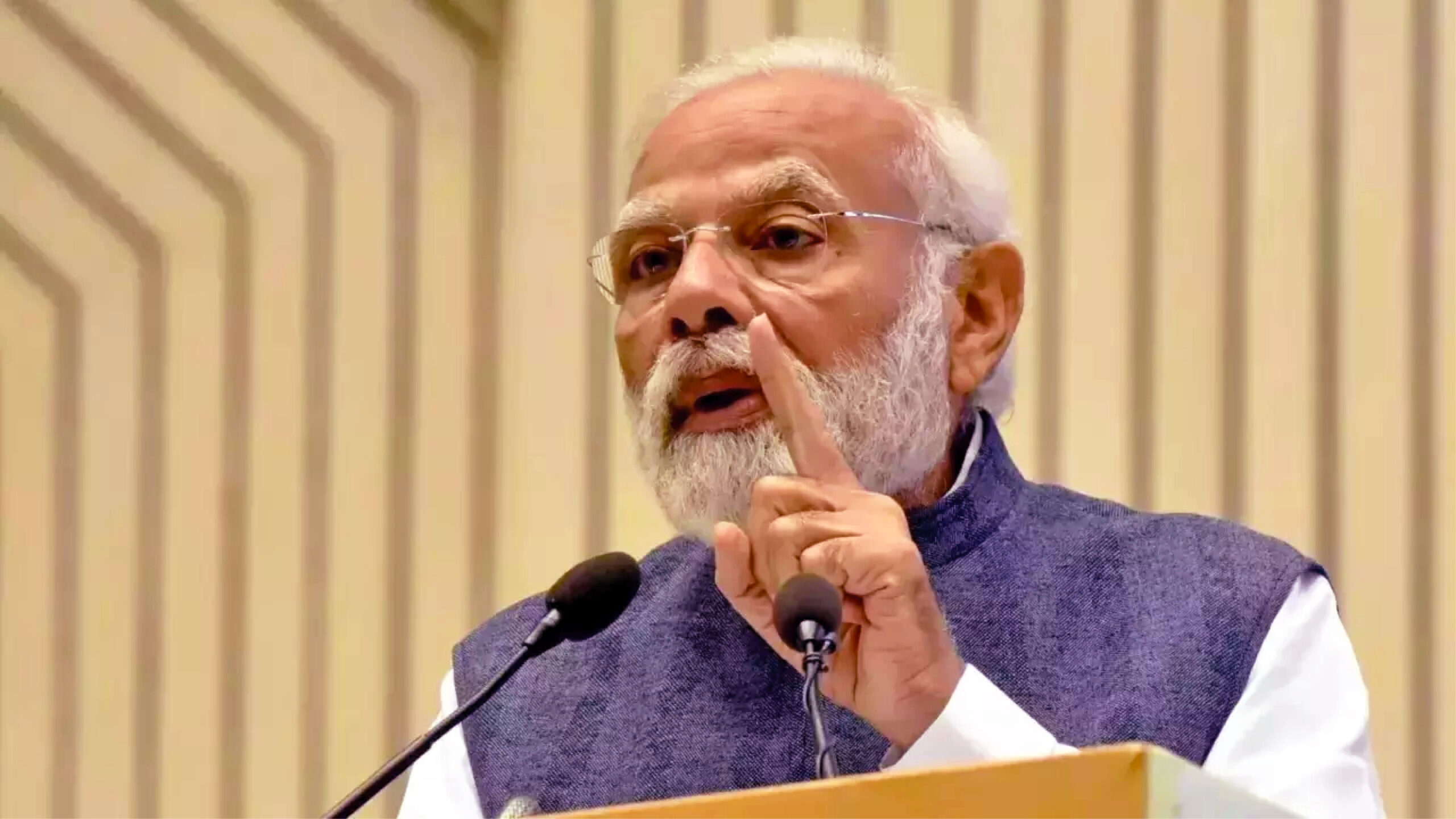

During an interaction with the media last week, Prime Minister Narendra Modi flagged the problem of deepfake. He spoke of a video where he was shown doing garba and how it was being forwarded even by his supporters. Deepfake is a serious problem. Deepfakes are manipulated video and audio recordings that use artificial intelligence to create fabrications, often superimposing or replacing content in a manner that it appears genuine. Deepfakes appear to be more authentic than any fake/morphed video or audio and that’s why they are more dangerous. By using AI, facial expressions can be altered, voices can be imitated, movements and gestures can be reproduced to the extent that there is no way of knowing that it’s not authentic, unless examined using deepfake-detecting tools. Even when these fake videos are not meant to malign the reputation of public figures, or private individuals, these open up the scary prospect of manipulating content with the purpose to deceive and disrupt.

Imagine a deepfake video or audio landing in newsrooms of Vladimir Putin ordering a nuclear attack on Ukraine, and it getting telecast/uploaded by the respective media outlets without authenticating the information in the zeal to break news first. Think of the turbulence it may cause in the stock markets, even though momentarily, making some unscrupulous people very rich and others lose wealth. It is here that the role of the media, particularly the news disseminating agencies, becomes important, for it is their job to carry out due diligence and verify the video or audio by cross checking with sources from the ground. Media organisations, in general, exercise a great degree of self-control and have a mechanism in place to verify “information” before they float any news. Even then many news organisations worldwide have been duped by fake videos on attacks and counter attacks in the Ukrainian war, to give one example.

The bigger problem is with social media. Deepfake videos/audios can be created to besmirch reputations, where any public figure can be made to say anything, including confessing to an imaginary crime, or be shown in a compromised position. Such content is unlikely to be picked up by mainstream media, but has the potential to go viral on messaging platforms such as WhatsApp, Telegram and others. While social media and microblogging sites such as Facebook and X, formerly Twitter, may be able to exercise some control over deepfake content by fact-checking them and blocking their spread, there is no such control, yet, on these messaging platforms, and it is these platforms that have the maximum reach among the public. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the misuse of WhatsApp by vested interests has reached epidemic proportions, and it is only a very few—in fact not even a handful—who will actually cross check the “information” that is inundating WhatsApp. Worse, there are millions of gullible people who believe such “information”. The potential for such “information” to cause public disturbance is known, as in India we have seen how riots have started over fake news circulated on messaging platforms. One of the reasons behind Internet shutdowns in India in times of trouble is to stop the spread of disinformation and misinformation via messaging platforms. Add to it deepfake and we are staring down a rabbit hole. Take a July 2023 news as example. A Kerala man was duped of Rs 40,000 when a criminal used deepfake technology to impersonate the man’s friend over a video call and asked for money from him. This is scary.

Of course even deepfake has its uses, especially in the world of entertainment where visual effects have a major role to play. There are instances of historical events being recreated, of dead actors being resurrected, or showing the ageing of a person onscreen with the help of deepfake. Even for training purposes, certain conditions can be created with the use of deepfake, particularly in the field of medical studies. But currently, deepfake’s potential to cause harm is far bigger than its benefits.

The need of the hour is regulation. The Central government wants social media platforms to remove deepfake content inside 36 hours of it being reported by users. Failing to do so may make these platforms lose their “safe harbour immunity” and open them up to criminal and judicial proceedings. Media reports say that the government also wants these platforms to reveal the source code or the identity of the first originator of any deepfake video or audio clip as part of the Information Technology (IT) Rules, 2021. But Facebook and WhatsApp have already gone to court over this clause in the IT Rules and the case is currently sub judice. Given that these platforms are wary about revealing any such information to the authorities on the ground of breach of privacy, the expected move over deepfake too may become a point of prolonged legal battle, without any solution in sight in the near future. Hence, the least that these messaging platforms can do is to introduce tools that clearly mark these clips as deepfake, or stop their dissemination if construed to be spreading misinformation and disinformation.

It’s only technology that can counter technology, and there is no reason why companies that spend billions of dollars to develop new technology, cannot shield their users from deepfake. The government too needs to work in mission mode to spread awareness among the masses about deepfake. Deepfake’s potential to unleash chaos must be blunted.