INTRODUCTION

A Federal Constitution is one, where there is a distinction between the Centre and States, such that the former cannot, beyond a certain point, ingress into the areas of the operation of the latter and in case of such a breach, the Judiciary has the authority to decide upon its legitimacy. This suggests that such forms of governments are inherently rigid and may affect governance to a greater extent, especially in cases of ideological clashes between the one’s ruling the States and those holding power at the Centre. To avoid this chaos, the leaders of the Constituent Assembly deliberated extensively on the said topic and asserted the existence of a strong Central Government, which would assure the autonomy of the provinces to a greater extent. This was done, primarily because India, unlike the United States of America, did not involve the “States” coming together and forming the Government, besides the age-old history of the Indian populace for striving for personal liberty of their domains, rather than uniting as one. That is to say, that India could not and did not adopt the principles of Federalism in verbatim, and the learned leaders declared India as a “flexible federalism”:

That is to say, India laid the foundation for a both Unitary and a Federal Constitution, where these two factions were mutually exclusive. The characteristic of the Federation was to change, depending upon the situation it was in – normally, it was to remain Federal, or, as is it referred to as today, a Quasi-Federal one, with always, a powerful Centre.

The Indian leaders, wellaware of the need for recognizing this diversity without compromising upon their agenda of establishing a “strong centre”, divided the provinces based on a linguistic and historical basis. And while these identities have strengthened, with time, these Constitutional demarcations, read with the democratic set-up, have paved the path for the possibility of different political parties ruling at the Centre and the State. These divergences have certainly engendered power struggles, affecting the growth and development therein, besides impacting the democratic rights of the citizens. For instance, the Central Government, where the authority managing the affairs of the State is not affiliated with it, is likely to ignore the needs of the State or destabilize it in some way or the other. Breakdown of the constitution machinery governing the state has been resorted to, by the Central Government for ensuring President’s rule in the region. This power has its roots in Article 356 of the Constitution, which can only be exercised when the President is convinced that it is imperative to do so, in the best interests of the citizens of that region – it is not absolute power. In Jammu and Kashmir, for instance, the emergency was declared for 6 years, as against Punjab, where it is believed to have lasted for around 10 years, continuously for 5 years. Such approaches were undertaken, unless there is a real threat, by the Centre to violate not only the nuances of the Indian Federalism but tend to increase the animosity between the political parties of different ideologies.

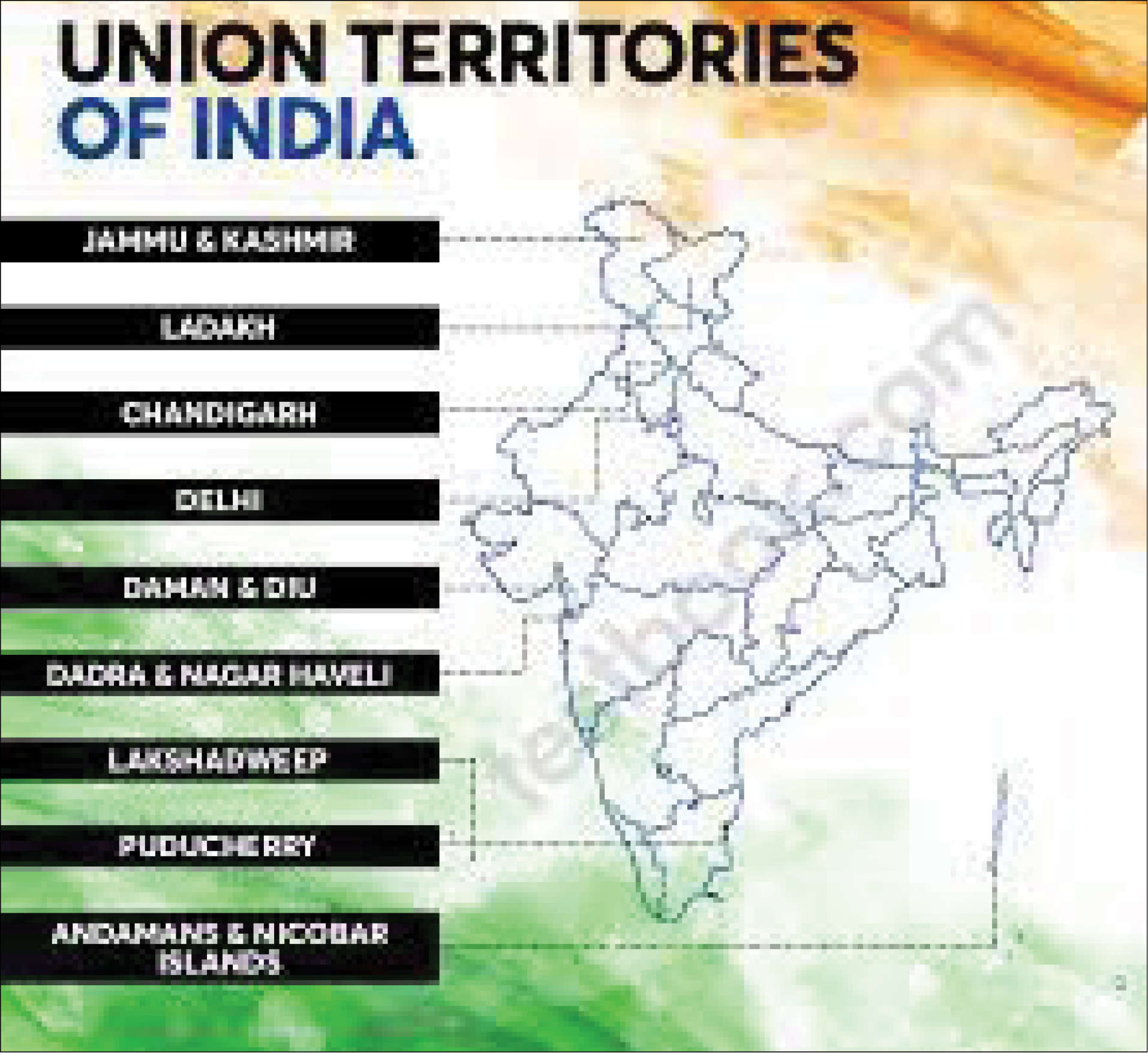

STATUS OF NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI IN THE QUASI-FEDERATION OF INDIA

Delhi, since time immemorial, has had a mythological and symbolic significance and being the Royal seat of a united India for virtually 800 years before the British dominance, it is not surprising that they chose to shift the capital of the Raj therein, in 1911. Since then, Delhi has continued to be the administrative capital of the region, even today, possessing a sentimental value. Interestingly, however, Delhi itself, also comprises its legislature, the executive and the judiciary -despite being a Union Territory, it enjoys the privileges which are often vested with other states. That is to say, that the National Parliament and the State Legislature, both operate in Delhi – the latter was bestowed with the said privilege through the Delhi Administration Act, 1966.

This certainly makes one wonder about the exact position of Delhi in the Indian Federation. Article 239 ideally permits the same administrator to act independently, since it is primarily a Union territory – this engenders the conflict between the mannerism of interpreting “Delhi”. Herein, it is important to mention that the Supreme Court in Devji Vallabhbhai Tandel and others v. Administrator of Goa, Daman and Diu and Another, went to the extent of declaring that in case of a conflict of opinion between the Governor and the Council of Ministers, the final decision would vest with the Central Government, with which, the latter would be required to be bound by.

Interestingly, the Supreme Court in New Delhi Municipal Corporation v. the State of Punjab, held that the power of Delhi’s Legislature to make powers is limited, especially in matters relating to police, land and public order. Herein, it is important to mention that, Federalism forms an inherent part of the basic structure of the supreme law of the land and therefore, cannot be ideally trampled with by the Central Government, indicating that any attempt to alter Delhi’s existing sovereignty is ideally impermissible.

And therefore, when the Central Government tried interfering immensely in the very operation of the affairs of the Delhi’s Legislature through the Lt. Governor, because it was a Union Territory, the Constituent Bench of the Supreme Court, in Government of NCT of Delhi v. Union of India and Anr, refused to treat it like any other Union territories or even give it the status of the State. In doing so, it affirmed that “Delhi” was a class within itself, and therefore, the Lt. Governor was under an obligation to merely assist the Legislature. It appears that while defining the separate identity of the National Capital of Delhi, this Court, however, reiterated and implemented the similar principles that guided the Governor’s powers to other states. Upholding the interpretation of Article 239AA, it held that the very purpose for introducing the said provision was to ensure differential treatment for the National Capital. Furthermore, it elaborated that Article 239AA(4), vested the executive power of Delhi vested with its Legislature, affirming that the Lieutenant Governor need not, in a mechanical manner, refer every decision of his Ministers to the President. That is to say, that the Lt. Governor should be apprised with the decisions of the Council of Ministers, but he cannot raise an issue with such undertakings, on every occasion. To present the decision before such Administrator does not, according to the Court, imply the need for taking his or her consent, but, is to keep him updated with the governance of the territory. And any difference of opinion, then, could be resolved through dialogue and discussion, as expected by Rule 49 of the Transaction of Business of the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi Rules, 1993, rather than taking the matter to the President directly – this was, according to the Court, likely to uphold the autonomy of Delhi and thus, safeguard the principles of Federalism in India.

In a nutshell, it relied on the relevant provisions of the National Capital Territory of Delhi Act, 1991 for showcasing that the Lt. Governor was expected to only act independently in matters where the matters were outside of the scope of the “legislative competence” of the Delhi Legislature or where he was performing the duties entrusted by the President. In February 2019, however, the same Court, in Govt. of NCT of Delhi v. Union of India, held that the Legislature of Delhi had no authority to make laws with regards to Entry 41 of List II of Schedule VII of the Constitution; it also dictated the instances in which the Delhi Legislature and the Centre could dictate terms. And just when the aforesaid matter seemed resolved, the Central Gove r n m e nt e n ac t e d t h e Government of National Capital Territory (GNCT) of Delhi (Amendment) Act, 2021, which essentially amended the certain, relevant sections of the Act of 1991. Practically, it declares that “government”, for any law made by the Legislative Assembly suggests “Lt. Governor”, adding that his or her opinion was to be undertaken by the Legislature mandatorily before undertaking any executive action. By amending Section 23 of the Principal Act, it paves the path for the Lt. Governor to reserve bills for the President which “incidentally” cover matters which ideally fall within the purview of the Legislature of Delhi. Besides prohibiting it to make any rules for “enabling” itself, it mandates the Delhi Legislature to take the opinion of Lt. Governor.

According to the Statement and Objects of this new Act, it would ensure the promotion of harmonious relations between the Legislature and the Executive besides demarcating the responsibilities of the elected Government and the Lt. Governor. On the contrary, however, it certainly seems to violate Article 239AA(4), which primarily deems the role of a person in the position of the Lt. Governor to merely aid and assist the elected Government – herein, the former seems to have become the whole and sole ruler, on behalf of the President and hence, the Centre. That is to say, that the elected government, irrespective of its political affiliation, would hereafter become a puppet of the one ruling at the centre, which is against the spirit of Indian democracy. Such an approach is an attack on the federalist structure of India, which is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution, ideally, cannot be amended to such great lengths.

CONCLUSION WITH EXPECTATIONS

Ideally, in the Quasi-Federal Indian State, the Centre and the State are expected to balance their desires and ambitions in such a manner, that the unwarranted or uncalled interference by the Centre within the administration of the States is disallowed. Within the arena of operation of the States, they are supreme and the interference in the Centre in such matters is ideally unjustified. However, the aforesaid is purely an attempt to abrogate the existing structure of Indian Federalism besides violating the relevant constitutional autonomy guaranteed to Delhi – besides, it subdues the democratically elected government therein, which cannot be tolerated.

One can certainly draw parallels of this incident with the approach undertaken by the Centre with regards to withdrawing the constitutional autonomy assured to Jammu and Kashmir. Since it has been declared as Union Territory, it is too, subjected to the norms of governance by the Centre and is managed by the Lt. Governor, so appointed by the Centre. Nevertheless, since its inception, it has been under President’s Rule, becoming the finest example of the Central Government exerting its influence directly over the region, unlike Delhi, where it is doing so indirectly and irrationally.

In both these cases, an elected government is virtually being reduced to nothing but a subject of the Centre, thereby making a mockery of the citizens right to vote their candidates to power in this region. This conflicts with the principles of democracy and certainly needs to be rectified at the earliest if the blatant violation of the Constitutional principles is to be avoided.