There was nothing in the old Hindu monk’s life till his ship reached New York in 1965, which suggested that he might have such influence. In fact, by all counts, Abhay Charan De, before he turned to monastic life and was given the name Bhaktivedanta Swami, had led a modest life. He had been born to parents who would today be called middle-class parents, though there had been considerable money in the family history. He seemed destined to have a regular, normal life. De grew up in British-ruled India and did all usual things of the time—a vaunted Christian missionary education, an early marriage and a suitably mercantile job.

But De perhaps always had a feeling that something was missing. He was born in a family devoted to Vaishnavism. Vaishnavism is the stream of Hinduism that worships Vishnu, the preserver in the Hindu trinity. The avatar of Vishnu preferred by many Vaishnavites is Krishna, the divine charioteer in the war of Kurukshetra in the Mahabharata and interlocutor in the Bhagavad Gita.

The worship of Krishna and his divine consort Radha was a hereditary act of faith for the Des. Krishna was the family deity, and while the young Abhay Charan had shown deep interest in spirituality even as a boy, it was inconceivable that he would turn to monkhood.

And yet, a chance encounter with his spiritual master, Bhaktisiddhanta Saraswati Thakur, transformed De’s life, and he renounced, in the age-old tradition of Indian asceticism, his family and his worldly belongings, to live as a sadhu, a mendicant in lifelong service of Krishna and to spread the word of Krishna.

If the story would just have been about Abhay Charan De becoming a monk and preaching in India, it would have been an interesting, though not a pathbreaking tale. But De, who received the name Bhaktivedanta Swami, would have what can only be described as a late-life renaissance—at seventy, he would cross the high seas to preach the word of Krishna in America, in the West and around the world as his guru instructed him.

He arrived with neither cash nor contacts. And trawled the streets of New York chanting the name of Krishna, hoping to attract and convince a few Americans of the power of the name of God. He did more than gain a few followers. He founded the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON).

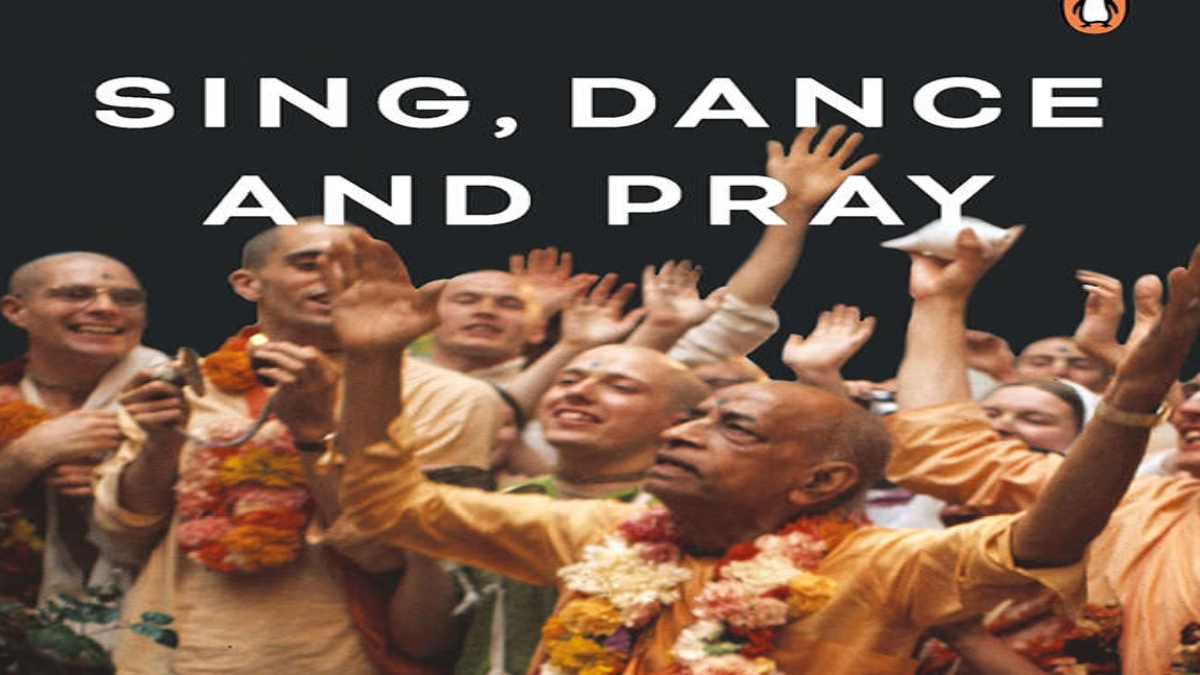

Soon in cities and towns across America, the sight of tonsured men in ochre robes and women in saris, singing and dancing, clanging cymbals, and playing the dhol, usually draped around their shoulders, created a wave which would, eventually, touch every part of the globe, and come to be known as the Hare Krishna movement, no doubt because its joyous devotees repeated, again and again, the mantra—Hare Krishna.

By around 1967–1968, as his fame started to spread in the West, Bhaktivedanta Swami née Abhay Charan De came to be known as Srila Prabhupada. The moniker has particular significance in Vaishnavism and other eastern philosophies. ‘Prabhupada’ means, in Sanskrit, the person who is devoted at the lotus feet of the lord, in this case, Vishnu. The reference of the lotus comes from the idea that the flower is born amidst dirt and mud and is yet itself untouched by the squalor that surrounds it. The feet of the lord are therefore that sacred point— which while being in touch with the dust of the world, remain unsullied by it—and thus a refuge for all those who seek a haven at it. The way, or path, to receiving the lord’s benediction is to submit completely at his lotus feet.

The name Prabhupada was given to Bhaktivedanta Swami to signify his utter sense of surrender to the will of Lord Krishna, ever at the feet of the lord. But this was not the first unique name he would receive. Even the term ‘Bhaktivedanta’, to those who study Hindu philosophy, would strike as a curious combination. Vedanta is usually understood (or misunderstood, as the Vaishnava Acharyas will argue) to describe a route of attaining the knowledge of the divine through contemplation on a formless, omnipotent,omnipresent Absolute Truth (the Vaishnava Acharyas too have written most elaborate and exacting commentaries on Vedanta that establish the transcendental form of Vishnu as the ultimate Absolute Truth). Or it is by knowing oneself, as the BrihadaranyakaUpanishad suggests, one knows the universe. The path of bhaktior devotion is almost always towards a divine with form—sagunas opposed to nirgun, or with transcendental qualities as opposed to without qualities.

Mostly, in Hindu philosophy, it is commonly understood that Bhakti and Vedanta stand at different ends of perceiving the truth about the divine. By combining the two and making it ‘Bhaktivedanta’, the Vaishnavite scholars of Chaitanya tradition were conveying something important—here was a man who had, in a sense, brought these two impossible-to-converge elements uniquely together. Genuine bhakti or devotion is not sentimental but founded firmly on the understanding of Vedanta. Without decrying the merits of the Vedanta path, the Swami seemed to show how it culminates into bhakti. That the end of contemplation on Vedanta comes God realisation which can only engender the deepest devotion or bhakti. Though not discussed enough, this idea of convergence, controversial as it sounds, lay at the heart of Srila Prabhupada’s theology. After Swami Vivekananda, who in 1893 created history with his speech at the Parliament of Religions in Chicago, the next most important date for what I would like to refer to as ‘global Hinduism’ surely would be 17 September 1965—the day Prabhupada arrived in New York.

In twelve short years, Prabhupada created a global movement that has far outlived him. In his own lifetime, he created a large following not only in the US and Europe but across all continents. Like Vivekananda, he continues to attract followers from around the world.

The excerpt is from ‘Sing, Dance, and Pray: The Inspirational Story of Srila Prabhupada Founder-Acharya of ISKCON’ (published by Penguin Random House India).