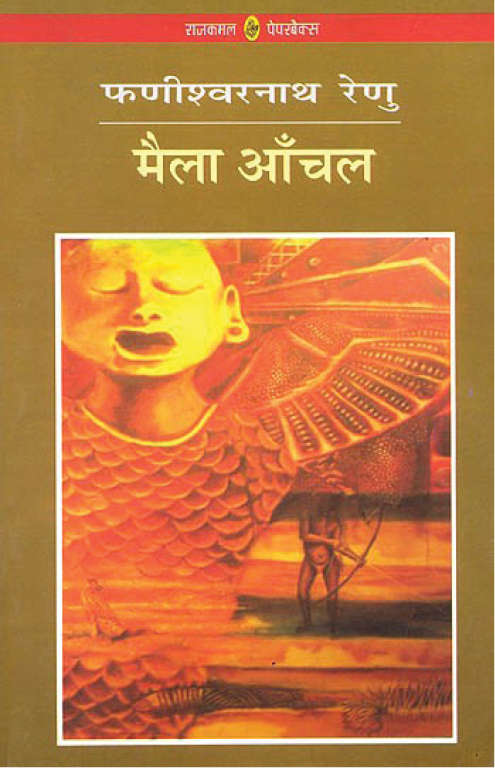

I write this article to remember Phanishwar Nath ‘Renu’ whose birth centenary celebrations were preempted by the onslaught of Covid-19 which has wrecked havoc on countless people across the world. He is a major twentieth century Hindi writer who wrote socio-politically relevant short-stories and novels. With the publication of his maiden novel, Maila Aachal in 1954, he dramatically emerged as a highly successful and extremely influential novelist after Munshi Premchand who had revolutionised Hindi literature by writing about a dozen novels including Godaan in 1936—the year Premchand passed way after presiding over the inaugural ceremony of Progressive Writer’s Association (PWA). Renu’s Maila Aachal in many ways took the entire Hindi literary world by storm. It generated some controversies but tremendous amount of euphoria and jubilation all around.

The idea of Maila Aanchal came from this poem, Bharat Mata Gramvashini, by Sumitanandan Pant who has given us an explicit portrayal of the figure of mother India who is kind of desolate and destitute and whose aanchal is sort of maila. Renu picked up this idea and wrote a classic which actually triggered an intriguing and long-drawn out war of words between two predominant literary camps of the then north India, namely progressives and experimentalists (as they were often called) who fought on the issue whether Premchand or Renu is better equipped to represent Indian rural realities.

Maila Aanchal tells us the tale of an emergent nation from the shackles of British rule, which has again sunk into all kinds of regressive practices for the unbridled and unethical material aggrandisement. The kind of social legitimacy these practices began to gain in Indian villages immediately after Independence explains the beginning of our postcolonial experience in modern India. But the reception of Maila Aanchal in the mainstream of Hindi literary criticism follows a different trajectory altogether. When the dust has finally settled over the controversies associated with the worth and impact of Maila Aanchal in the immediate aftermath of its publication some 66 years before, one can safely reflect on the ways in which the reception of the novel took place in Hindi heartland against the backdrop of provocative but serious debates about the concepts of “Aanchalik Upanyasa” (Provincial novel) and “Premchand Ki Parampara” (the tradition of Premchand).

Allahabad-based literary initiative under the umbrella of Parimal with which literary figures like Dharmavir Bharti and Vijyadev Narayan Sahi were associated, was undoubtedly responsible for the critical acclaim of Maila Aanchal at an early stage of its reception. Bharti, the author of the famous play, Andha Yuga, the then editor of prestigious Hindi literary journal, Alochana, is often mentioned as someone who made that kind of helpful and genuine reception possible. But even before Bharti could bestow deserving but generous praise upon Renu whom the former declared the Vidyapati of Mithila in Hindi prose, Nalin Vimochan Sharma, the noted Patna-based critic of Yesteryears in Hindi, brought Maila Aanchal to the notice of Hindi readership. Writing probably the earliest review of the novel, he drew the attention of the academic scholar and critics alike to the abundant merits of the novel. Sharma looked at Renu’s maiden novel in comparison with Premchand masterpiece, Godaan, which he found far more superior in terms of its epic-scale representations of human condition and its crystallisation of grand-narratives for all major issues involving the Indian village life. He believed Maila Aanchal to be representative of just a specific Indian village, whereas Godaan represented each and every Indian village.

But he termed Maila Aanchal the best Hindi novel after Godaan and placed Renu in the tradition of Premchand. Probably because of the intellectual and ideological differences between Parimal and Progressive Writers Association, Ramvilas Sharma, an active member of PWA, left no stone unturned to demolish Renu, perhaps to contain his literary rival, Bharti, too. In his book Premchand aur Unka Yug, he forcefully attempted to dissociate Renu from the tradition of novel-writing initiated by Premchand. Following Ramvilas Sharma, the entire debate began to revolve around the idea of provincial novel (Aanchalik Upanya) and its relationship with the tradition established by Premchand.

Later, Shivdan Singh Chuahan, the founder editor of Aalochana and an active member of PWA as well, set the record straight when he categorically pointed out that distinction made between Godaan representing the entire Indian village and Maila Aanchal only the province of a district is defective and flawed as Renu’s novel embodies as much village-life and its richness in terms of cultural traditions, myths, languages and social experiences as Premchan’s Godaan. Chuahan insisted that no comparison should be made between the first novel of Renu and the last novel of Premchand even while he gave Maila Aanchal the kind of reception that reinforces its popular recognition as a classic across different schools of literary thought in Hindi.

In Hindi literary cultures or what Francesca Orsini has defined as the Hindi public sphere, the reception of Maila Aanchal has taken place as a classic of Hindi literature which narrates the nation as it has emerged in the aftermath of Indian independence. Except some of the early hostile criticism associated with this text, successive generations of literary critics in Hindi have gone on to appreciate this text without ever suggesting the idea that they should be understood and interpreted as post-colonial texts. Two volumes of Aadhunik Hindi Upanyasa (Modern Hindi Novels, which offers us a collection of critical essays on modern Hindi novels), published by Rajkamal Prakashan, a reputed publication in Hindi, have the same story to tell us about this text as far as the genre of the novel is concerned. The comprehensive and perceptive introduction written by Virendra Yadav, a well-known literary critic in Hindi, in the second volume of Modern Hindi Novels, categorically points out the status of classic Maila Aanchal holds in Hindi literary traditions. That this novel is a genuinely postcolonial text was indicated in an article “Indian and Postcolonial discourse” written by bilingual literary critic Harish Trivedi in the book Interrogating Post-colonialism, jointly edited by Trivedi and Meenakshi Mukherjee.

Maila Aanchal identifies the sources of and underlines the instances of the decline of our nationalist values in its multi-layered narratives shaped and sustained not only by the unconventional and even adventurous story of doctor Prasant and his beloved, Kamli, but also by the immense courage and inspirational sacrifice of the Gandhian figure, Bawandas. Whereas Premchand contributed a great deal to the reawakening of our national consciousness in his literary endeavours by writing the idea of Gandhi in myriad ways, Renu did tell us shocking and rather systematic demise of Gandhian principles during the very early years of independent India.

This novel is a classic creative reflection on the ways in which Gandhi began to be increasingly irrelevant in the immediate aftermath of Independence in Indian socio-political discourse and public life leading to his physical death symbolised by the ruthless annihilation of Bawandas in the novel in discussion. It is as difficult to erase the memory associated with the figure of honest and nonviolent Bawandas who stands for Gandhi himself and whose values were already put to the periphery as that of Renu, arguably one of the three best novelists in Hindi.

Maila Aachal begins with the opening of a hospital for the eradication of the disease called malaria. Dr Prashant, a medical genius, is posted there. He finds out the real reasons for the outbreak of malaria. According to Prashant, they are poverty and ignorance. Not only in the beginning but even in the later parts of the novel which brings to the fore those broken dreams which nationalists like Gandhi envisioned but hypocritical politicians and postcolonial citizens alike demolished because of their greed and ignorance, Renu highlights misperceptions and misplaced priorities of both socio-politically and medically endangered society.

The daily loss of lives followed by heart-wrenching pain and pathos with which people are reeling under terribly dark circumstances due to flawed response to the pandemic does tell us a similar story, but Renu is sadly conspicuous by his absence to create another classic.

The writer is Assistant professor in English, Rajdhani College, University of Delhi.